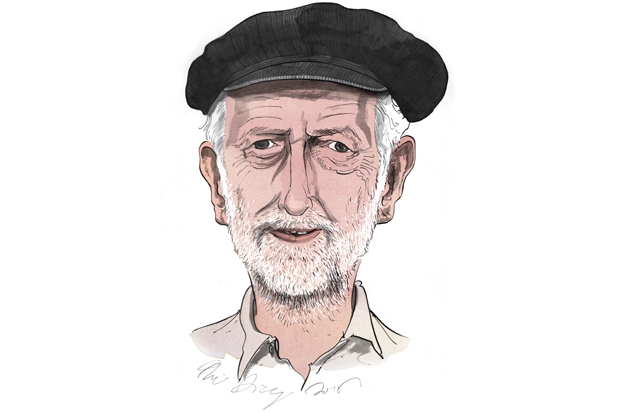

Why haven’t some Labour MPs ever met Jeremy Corbyn? Mr Steerpike picks up on the discussion between former Miliband aide Anna Yearley, and MPs Barbara Keeley and Lucy Powell about his non-attendance at PLP meetings and the fact that Powell has ‘never, ever met or spoken to him’. This is odd: Corbyn has been a member since 1983 and has managed to find time to befriend Ukip’s Douglas Carswell, who cheerily offered to introduce Yearley to Corbyn in the tearooms at some point.

It’s not unusual, though: on Sunday night Tory backbencher Mark Field was singing the praises of the friendly Corbyn on Westminster Hour. But when I was discussing Corbyn’s appeal with a Labour frontbencher whose judgement I’ve always trusted, he looked rather dubious when I said I thought he was a decent and pleasant man, and said ‘well, the only thing Jeremy said he’d do for me, he then didn’t do.’ At least they’ve met, though.

Perhaps the reason Corbyn has such strong support among Tory backbenchers and ex-Tory backbenchers is that they share the same way of doing politics: being principled means not going too near power and refusing to do anything that they disagree with. This is what makes Corbyn appealing to those outside the Westminster village because his way of doing politics is quite clear-cut: I’ll only support what I agree with sounds like the way a lot of ‘normal’ people would like to conduct themselves in Parliament. The thought of walking through a voting lobby in support of a policy you think is wrong is anathema to many people, not just angry hard lefties who have funny views about Nato.

Now, this attitude probably upsets those of Corbyn’s colleagues who do hold frontbench positions or who choose to be loyal backbenchers. It implies that they don’t have principles, even though they would argue that power is the means by which you start exercising, rather than pontificating, about those principles.

But there is a balance to be struck here, and I’m not sure the parties in Parliament get it quite right. They do crush dissent from perfectly sensible MPs about policies those parliamentarians are worried about. If you exhaust the private channels for raising concern about a policy and end up giving a journalist a quote about that policy to try to further pressure ministers, you get a screaming early morning call from a whip or minister telling you to desist and accusing you of damaging the party. Or else you keep your head down because there’s something you’d like to accomplish as a minister and the price of doing something good and worthy in a government department is often not fulfilling your scrutiny role as a backbencher. The whips’ powers of patronage have weakened a little in recent years, with elections to select committees and a growing reluctance on the part of backbench MPs to take menial PPS roles, but the legislature is by no means free.

Some, like Corbyn, don’t fancy being a minister anyway and so the decision is easy: rebel all you like because your career trajectory doesn’t depend on being loyal. Corbyn wouldn’t have enjoyed being a minister or a shadow minister because his talents are in debating ideas, stirring up crowds and attending protests. He is not a manager. It’s probably why he gets on better with Douglas Carswell, who is similarly gifted at writing well, sounding interesting in broadcasts and giving impassioned speeches but has never shown much interest in the frontbench of either of the parties he has been an MP in. Their colleagues with different gifts are often pretty rubbish at these things (anyone who has had to edit MPs’ copy knows that Carswell is a rare bird indeed when it comes to being able to write stuff you want to read), but are good at the boring machinery of government and opposition – or at least try to be good at these things.

Perhaps these comments by Powell et al also illustrate a gulf between the elites of the Labour party and the less important, less glamorous backbenchers who nonetheless seem to have a great deal of purchase amongst the membership. Remember few in the PLP realised that Corbyn would get anything like the attention he has in this contest when they decided to have a bit of fun and put him on the ballot paper. There is clearly a gulf between the party and the membership, but there is also a gulf between different types of Labour MPs.

Whether or not this is a fair assessment of why some Labour MPs haven’t managed to talk to one of their longest-serving colleagues, it does show one thing: he’s got a huge task in getting the PLP, which largely doesn’t support him, to respect and follow him once he becomes leader. He says he wants to give more people a say in policy and to include them, but before any of that, he needs to meet them.

Comments