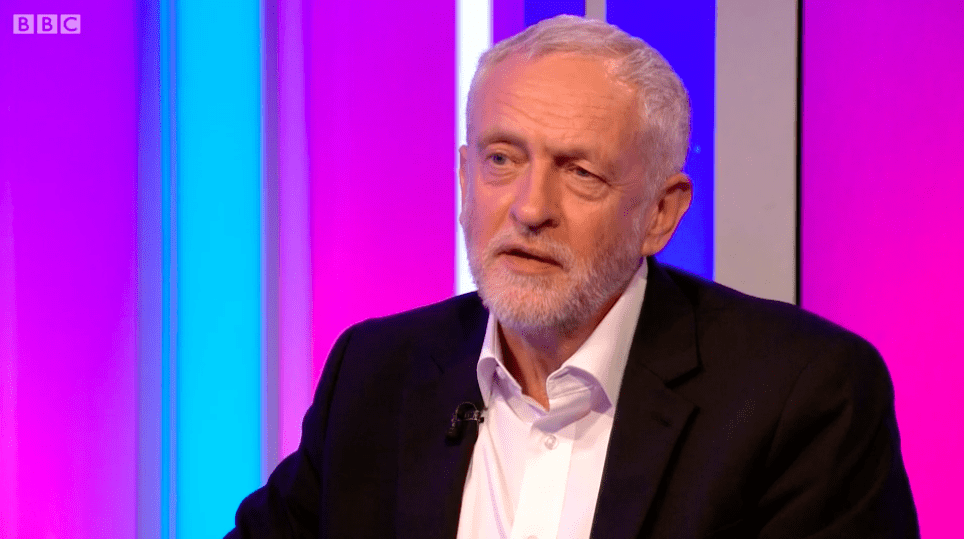

It started with a fib. Jeremy Corbyn endured a trial-by-sofa on BBC One last night and he was asked if there were ‘boys jobs’ and ‘girls jobs’ in his household. He shook his head. Which is a total porkie. He’d parked his missus at home while he answered questions on prime-time television. A clear division of labour. Boys speak up, girls shut up.

The presenters were so soft on him they might have been members of his campaign team. Maybe they are. He was allowed to dodge the awkward issue of Brexit.

‘What’s the biggest thing you’ve changed your mind over?’

‘What’s the biggest change in my life?’ he mused, deftly removing the toxic ingredients from the question. He said his principles had remained ‘pretty much the same’.

Who are easier to control – children or parliamentary Labour Party? pic.twitter.com/Dr4NBwU3UF— BBC The One Show (@BBCTheOneShow) May 30, 2017

Pictures from his family album were shown. We got a landscaped glimpse of his famous allotment which is chaotic, overgrown and entirely devoid of edible produce. A bit like Venezuela.

A pic of him wearing baby-reins prompted a reminiscence about his habit of escaping from his pram and running away. Always the rebel. That was the point.

What was Jeremy Corbyn like as a toddler? pic.twitter.com/yMO2MoDYdU— BBC The One Show (@BBCTheOneShow) May 30, 2017

We learned about his forebears. The parents, who met at an anti-Franco rally, raised their sons to think independently, to question, to read, to challenge. A colour shot of the family in the 1950s, (when colour prints were expensive), revealed three Corbyn brothers kitted out in splendid school blazers. Also expensive. Quite a prosperous house. With them sat Grandpa Corbyn, a genial oldster in a cream suit, who was a solicitor. His nickname, Corbyn told us, was the ‘poor man’s lawyer.’ Neat and subtle propaganda. We were being presented with a dynasty of compassionate activists. This was, in a way, the pitch of an aristocrat. I deserve to lead because I understand the precepts of libertarian dissent that have energised this country’s political heritage. In other words, I was born to rule.

His academic record came up. He left the sixth form with two Es at A-level. ‘I’ve got the certificates at home,’ he boasted with a twinkle, as if failure at school were a proof of merit. It’s hard to see how this will help Labour on polling day. No candidate, in the long annals of electoral democracy, has ever triumphed by capturing the ‘teenage half-wit’ vote.

How did Jeremy Corbyn do in his A-Levels? pic.twitter.com/L5bqCzHOVH— BBC The One Show (@BBCTheOneShow) May 30, 2017

The slide-show ended with a picture of aid-worker Corbyn in Jamaica. He was wearing casual whites like a colonial beatnik. A chunky watch encased his wrist. An expensive camera dangled from his shoulders.

What did he do in Jamaica? Everything. He virtually ran the place. He organised athletics competitions, he produced plays for youngsters, he helped out with kids at a polio clinic. What he didn’t mention, of course, is that the athletes went on strike, the plays were cancelled after a work-to-rule at the box-office, and the polio clinic was taken over by an anarchist collective which denounced polio as an imperialist plot.

For Corbyn this was a successful half hour. He seemed likeable, warm, decent, principled. A good bloke. And nothing like a machine politician. These are important advantages. But those around him must have spotted something alarming. A lack of energy. A big void where the hunger should be. He seemed as contented as a cat dozing in a shaft of sunlight. He was asked about his early political ambitions and he said, ‘Did I ever set out in life to become prime minister? No.’

It sounds odder the more you read it. He never set out to gain power? So why spearhead an election campaign and ask people to give him what he can’t recall desiring? Almost an admission of defeat.

Comments