I don’t get Johann Sebastian Bach. I mean, I get that he was good — no Mozart, sure, but definitely up there in anyone’s top five 18th-century composers. But that’s not enough. Bach must be revered as the One: the supreme and universal musical genius. When John Eliot Gardiner celebrated the millennium by performing Bach’s complete cantatas, it wasn’t a cycle or a series but a ‘pilgrimage’, if you please. (He’s back with more cantatas this weekend at the Barbican.) Playing Bach, we’re told, requires profound selflessness — though if you’ve ever witnessed a solo violinist hijacking an orchestral concert to saw through all 15 tortured minutes of the D minor Chaconne, you might call it something else entirely. No: as The Bluffer’s Guide to Music puts it, there’s only one acceptable response — to adopt a posture of open-mouthed reverence and intone the words ‘Ah… Bach.’

Well, you can say it, but what if you don’t feel it? I’m not alone: the pianist Stephen Hough admitted a few years ago, to gasps of horrified disbelief, that he didn’t feel a deep connection with Bach’s music. Is that really so appalling? Bach worship is a relatively modern phenomenon: Beethoven rated Handel far higher, and for Haydn and Mozart, old JSB wasn’t even the greatest composer in his own family (the music of Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emmanuel has suffered particularly unfairly from the cult of Dad). Meanwhile the man himself seems to have been an amiable curmudgeon, ploughing on with his job in his own old-fashioned way.

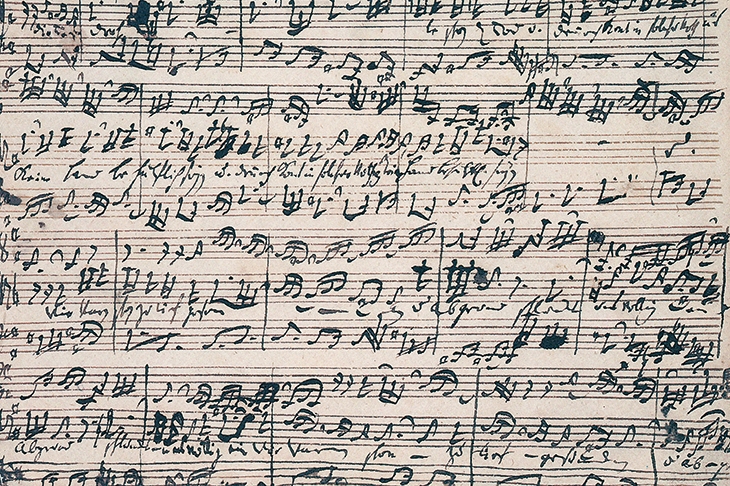

The music by Bach that speaks to me tends to date from the first half of his career, particularly his time in Cöthen in the early 1720s, where he enjoyed relative artistic freedom. The result is a great exuberant sunburst of creativity: the suites for solo cello, the Brandenburg Concertos, and the boisterous splendours of the orchestral suites. And then, in 1723, he accepted a church job in Leipzig. Game over: he churned out religious music on an industrial scale, and there’s treasure there, for sure. But that’s a lot of glum chorales, overwrought arias and Lutheran dogma to dig through first. Thou hast conquered, pale Galilean.

Bach’s church music speaks of medieval certainties, and I can see why today, as we retreat from Enlightenment values, it might fill a spiritual gap. Bach, wrote the Bluffer’s Guide back in 1971 (they wouldn’t get away with it now), ‘is adored by all intellectual virgins’. He wrote no operas, and died before the string quartet and symphony came of age: he’s not interested in creating rounded human characters, or starting a conversation. It’s the sound of an age that values earnestness over wit, and overbearing certainty above mischief and ambiguity. We get the music we deserve, and plenty of listeners would be glad to spend eternity with Bach’s pious note-spinning. I’d rather share my desert island with Papageno, Susanna, Don Giovanni and Countess Almaviva. My loss, no doubt. At his best, Bach is magnificent. But please, stop telling us he’s the universal composer, because there’s no such thing.

Comments