During the various lockdowns I found myself wondering how Iain Sinclair was coping with the restrictions. It seemed unthinkable that this unflinching punisher of pavements could be stuck with 30 minutes round the park. But, as it turns out, sequestering, in a fashion that only the Scots word ‘thrawn’ can do justice to, has resulted in the most archetypal Sinclair book yet.

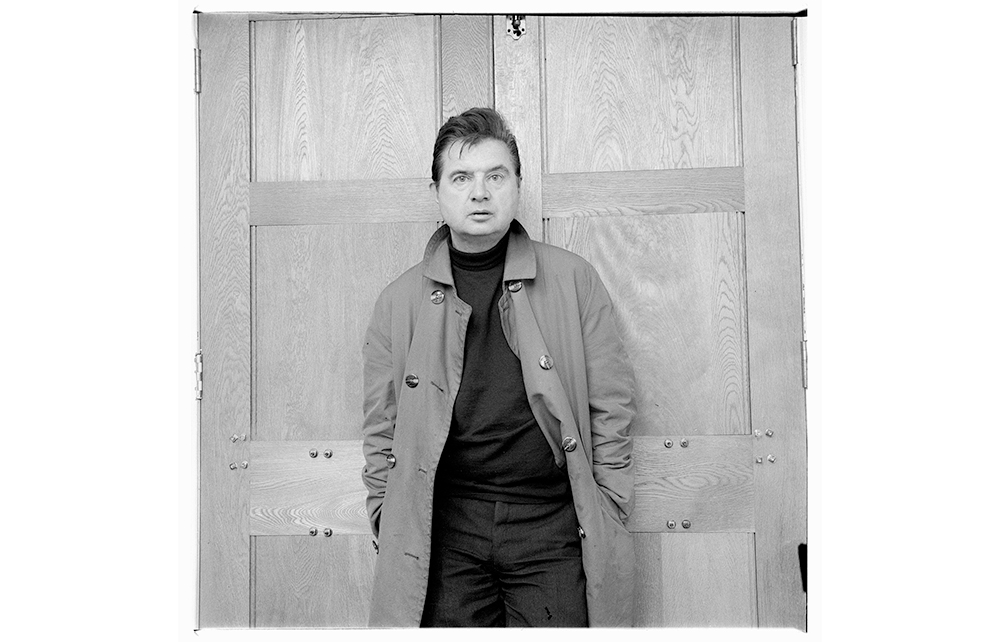

John Deakin is the pariah genius of the title. During the ‘brain-dead hibernation’ of the pandemic, Sinclair got a short-term loan of ‘17 albums of John Deakin’s photographs, fresh prints made from recovered contact sheets; a substantial history of his labours, a flickbook parade of the stunned and waxy faces of his time and place’. From this Sinclair tried to create a ‘psycho-biographic fiction’. The milieu and the manner suited him perfectly, and it seems ironic that the enforced inability to travel and the ‘resurrected eidolons of a story that was not mine to tell’ has created a far-flung book, taking in Wales, Malta, Paris, Rome, Athens and Tangiers, and ending with death in an insalubrious hotel in Brighton.

Deakin, to Sinclair, is rather like God to Voltaire: if he did not exist it would be necessary to invent him. He was not only the subject of paintings by Bacon, but his photographs were the basis of Bacon portraits. He was marginal and central, his role behind the camera being a search for willing victims. There was no attempt at best sides or good light. His subjects look like dress rehearsals for a morgue shot – not just Bacon, but Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud, as well as the poets George Barker and Dylan Thomas.

To Barbara Hutton, Deakin was the ‘second nastiest little man’ she had ever encountered

Deakin was the perfect anti-hero of the tawdry Soho scene. George Melly called him ‘a vicious little drunk of such inventive malice and implacable bitchiness that it’s surprising he didn’t choke on his own venom’. To Barbara Hutton, he was ‘the second nastiest little man’ she had ever encountered. (Sinclair, or posterity, draws a veil over the first.) Noël Coward warned: ‘Never let that man near me again.’ There was a sulphurous miasma to him; yet Sinclair manages to convey a hybrid of pity and admiration. With a kind of spiteful panache, Deakin named Bacon as his next of kin, forcing the artist to travel to Brighton to identify his body. In a way, Deakin forced Bacon to acknowledge him. It was, to use Deakin’s coinage, a horrible ‘obitchery’. As a last laugh, it may be whimpering but it is persistent.

‘It can feel,’ writes Sinclair, ‘to the conspiracy obsessive, initiated by the tarot of the albums, that the stalking photographer lurks somewhere at the back of all the cultural manifestations. He served, he provoked. He kept the record.’ The presence of the Krays and other avatars of crime gives a dark slant to the idea of potentially compromising snaps. But there is more to this than ghoulishness, particularly in the section on David Archer and the Parton Press. For Archer to have published many of the post-war surrealists and writers of the ‘New Apocalypse’ was no small achievement, even if the reward was being sponged off into penury.

Pariah Genius reminded me of a story in the cult 1980s television series Sapphire and Steel, where the antagonist, ‘The Shape’, is a featureless man hidden in every photograph who traps people in two dimensions. His look bears an uncanny resemblance to Hitler’s only known self-portrait. Sinclair is working with some of the same icons. His lexicon is occult as well as criminal. This is a world of negatives, dark rooms and transparencies. He inverts the old anthropological canard about groups such as the Amish, Native Americans or Arabs believing that the camera steals the soul. Sinclair presents Deakin’s imagined life as a form of botched exorcism, with the subjects warped, distorted and smeared like sitters in a Bacon painting.

Deakin’s archive becomes a wordless novel, with Sinclair tasked as the magus or critic to interpret what story it is telling. One sinister figure, Robinson, named after the transient character in the poetry of Weldon Kees, chides Sinclair that:

the quality that separates Deakin’s snaps… from an AI pastiche is spirit… And it would be child’s play to call up a simulacrum of your rather singular prose style. With a few words redacted, the book would write itself.

It is the old Sinclair refrain: ‘These fragments have I shored against my ruins.’

Comments