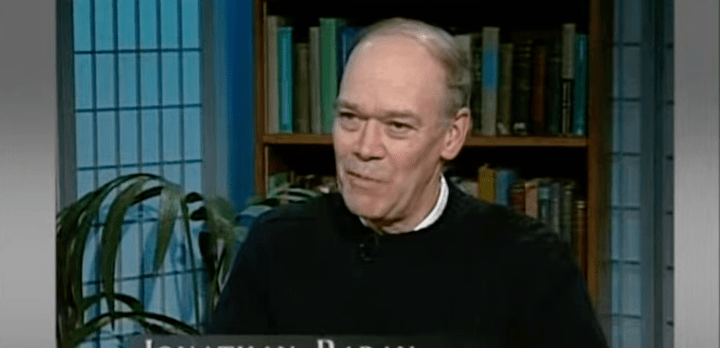

Jonathan Raban was largely responsible for changing the nature of travel writing. Back in the 1970s when he began, the genre still viewed the world from under the tilt of a Panama hat (‘I looked at the tops of the columns. Were they Doric or Ionic?’). It was considered ill bred for a writer to reveal anything about themselves; they were supposed to be a transparent pane of glass through which one could view the world.

Raban tore this up, and with glee. He had worked closely with American confessional poets like Robert Lowell and John Berryman, producing one of the best essays on Lowell’s late poems about his messy divorce. He had even been Lowell’s lodger for a while. Now he took the same transatlantic approach to travel writing and elicited the same chorus of disapproval the poets had experienced for being so personal. Yet it was patently as absurd for a writer not to tell the reader if he was going through emotional turmoil as it would be for a traveller not to tell a companion on that same journey. Even if they were both English.

Even Raban’s asides are glorious

He also took as his subject matter not the Mediterranean and Middle East, the traditional stomping ground for the men in the linen suits, but the brash new world. He returned to America again and again with something of the questioning obsession that Naipaul brought to his books on India.

The best of his American books is perhaps Hunting Mister Heartbreak, which takes its title from a poem by John Berryman. At the start of the book he announces that there is a sentence which always stirs the imagination of Europe and which promises to deliver the unexpected: ‘Having arrived in Liverpool, I took ship for the New World.’ Raban unpicks the appeal of these lines. It is not just that they are ‘so jaunty, so unreasonably larger than life’. It is that what turned the Atlantic passage into the great European adventure was not so much the nature of the country that awaited as the character of the ocean, ‘a space too big for you to be able to imagine yourself across’.

And this was Raban’s other great obsession. The sea. He recounts in his collected essays For Love & Money how he first came across sailing by accident when on a journalistic commission; and discovered that a small boat in a big ocean suited both him and his writing. The element of risk and unpredictability prevented any journey from becoming stale.

For Coasting, he set off around the shores of Britain just as the Falklands War was starting: so the book becomes an extended meditation on a country he sees as ‘a dark smear between the sea and the sky like the track of a grubby finger across a windowpane – a distant, northern land’. It is ‘a test, a reckoning, a voyage of territorial conquest, a homecoming’. At one point, he hallucinates his small boat is actually standing still and the entire landmass of England is steaming past him to head south and take part in the conflict. He has never been afraid of such bold literary strokes. As his writing matured, you can see him adopt some of the cadences of Robert Lowell’s poetry: the sudden shifts of thought and attention from the personal to the political, from history to the here and now.

There is a trope which often recurs in Raban’s sailing books. A spell of bad weather upsets his cabin so books and possessions are flung about. As he restores order, his thoughts turn to the disruptions in his own life, like divorce and his difficult, distant father. But then, before he can become too maudlin, the title of one of the books will suggest a renewed investigation of that subject and he will surge away on a tide of intellectual curiosity.

Raban’s muscular and intelligent style remain an inspiration. Even his asides are glorious, as when he tries to make eye contact with New Yorkers at a subway entrance and ‘they swerve away in their sockets, as quick as fish’.

In his books, he always pursued the detailed and sustained interrogation of a country and of himself: how America worked; what it wanted; what he wanted from it. He was never content merely to observe, let alone grandstand over epic journeys, although his sailing exploits off Alaska and his journey down the length of the Mississippi command respect for the achievement as much as for the writing.

Old Glory, the book that resulted from that Mississippi journey, was a bestseller of its day in 1981 and established him as a master of his craft in every sense. Along with Bruce Chatwin, he helped revive travel writing as a flexible form with infinite literary possibilities.

But if Chatwin treated travel writing as a playful and elegant game of tennis in which he could swan around the world in white flannels, Raban was more like a gnarly squash player with a sweat-stained headband who was mainly playing against himself.

Despite the most English of roots – the middle-class son of an Anglican vicar – he fell in love both with America and an American and, this being confessional travel writing, paid equal attention to both the country and the marriage in the resulting books. His last years were spent living in Seattle and despite ill-health he continued to produce both novels and essays.

Raban was never dull and often brilliant. However, there is a curious paradox at the heart of his work. For a writer who sets out to be confessional – who does indeed tell us much about his broken marriages and family background – he remains a curiously elusive personality. Perhaps it has to do with his quicksilver intelligence. But unlike his contemporaries Chatwin and Paul Theroux, I have a far less clear impression of who he was. He once said of his beloved Robert Lowell that however much he wrote about himself he remained ‘an unknowable man’ – indeed that was part of the point, because we are so complicated as people.

Without Raban and his cohort, we would have no Will Self ‘psychogeography’, no Geoff Dyer playing coy games with his persona in Jeff in Venice, no Cheryl Strayed licking her emotional wounds in Wild. Some, of course, may blame him for this. But the best travel writing, he constantly reminded us, is about more than just looking out of the window. It means also looking at our own reflection.

Comments