The epic story of the Antarctic voyage of the Belgica (1897-9) has all the ingredients of a truly glorious misadventure: an aristocratic expedition commander who carries the pride of a small nation on his shoulders; an eccentric American surgeon who was to become known as one of the greatest frauds in the history of polar exploration; a cantankerous crew, racked by madness, scurvy and mutiny; a desperate sunless polar winter stuck in shifting sea ice that threatens to crush the ship; and finally an escape plan that involves half a ton of explosives and hand-sawing through a mile and a half of sea ice. It is an extraordinary tale of ambition, folly, heroism and survival, superbly told by Julian Sancton, who has rescued the Belgica’s story from relative obscurity and brought it to magnificent life.

The opening quote of the book, by the would-be Everest conqueror George Mallory, sets the scene: ‘Sometimes science is the excuse for exploration. I think it is rarely the reason.’ For the well-born Belgian naval lieutenant Adrien de Gerlache the idea of commanding an expedition to the as-yet unexplored Antarctic was the fulfilment of not just a personal but a national dream. ‘The questions Why me? And why Belgium? do not seem to have occurred to him,’ writes Sancton. ‘Instead he asked himself, Why not me? Why not Belgium?’

Raising enough money for a Belgian polar expedition was not a problem. Two-and-a-half-thousand citizens stepped forward to crowdfund the venture: a schoolteacher gave one franc, a mailman three, a senator 1,000. Concerts, lectures, a cycling competition and hot-air balloon rides were organised. But with the massive support came a burden:

The journey that had lived only in de Gerlache’s mind for many years now lived, too, in the minds of his countrymen, hungry to share in the glory. He had made it real, but in doing so he had generated a national emotional investment that he had no choice but to pay back.

Finding enough Belgians qualified for (or crazy enough) to go proved more challenging. In the end de Gerlache accepted adventurous foreigners, notably a young Norwegian named Roald Amundsen and Frederick Albert Cook, an eccentric American doctor. Between them, they would save the lives of the entire crew.

Screams echoed in the polar night. One sailor became raving mad and tried to escape across the ice

Things began to unravel well before the Belgica reached Antarctic waters. De Gerlache proved too young and diffident to control a group of rebellious crewmen:

Ethnic rifts ran throughout the ship, dividing officers and crew: Norwegians vs Belgians, Dutch-speaking Belgians from Flanders vs French-speaking Belgians from Wallonia. Meanwhile, no one could get along with the belligerent French cook Lemonnier.

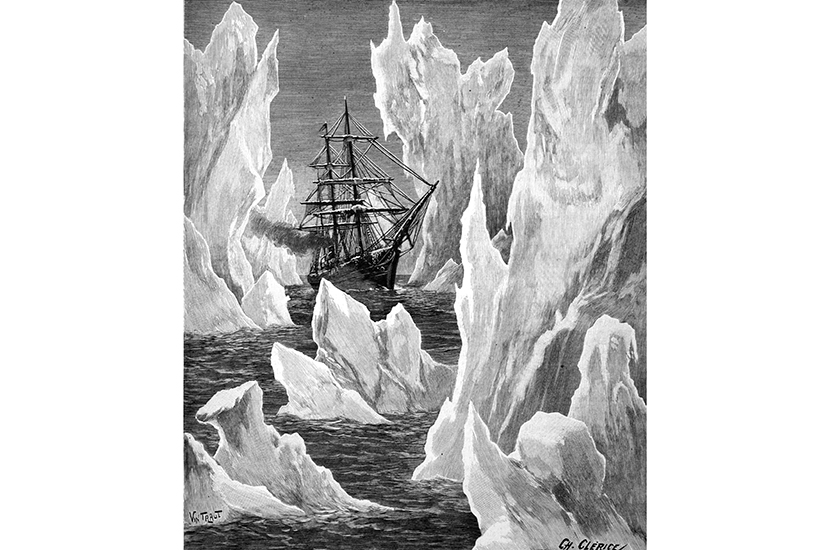

After weeks of drunkenness and insolence, the worst troublemakers mutinied in Punto Arenas at the southern tip of Chile and had to be arrested by a local gunboat. A storm carried away the expedition’s magnet-ologist, a childhood friend of de Gerlache’s, and despite the captain heroically jumping into the frozen sea to pull the man to safety, his hand slipped from his rescuer’s grip at the last moment and he was lost. By the time the ship reached the edge of the towering icebergs that marked the edge of the Antarctic polar ice cap, the summer of 1897 had all but slipped away.

As the Belgica steamed down what is today known as the De Gerlache Strait, the unexplored continent revealed itself in all its forbidding majesty. Captain Georges Lecointe observed:

The sun had dipped behind the mountains to the west but was still catching their peaks and illuminating the sparse clouds above, forming a golden canopy that stretched over the darkened valley and reflected against the blue-black water. Icebergs glided silently along, like apparitions.

The men on the ship had become ‘denizens of an icy Eden’, writes Sancton, ‘giving a name to every island, coast, cape and previously undiscovered species’. The expedition’s scientists gathered flora and fauna from the icy waters and rocky coasts. The Romanian naturalist Emile Racovitza’s treks across the barren landscape were rewarded by the discovery of the largest strictly terrestrial animal indigenous to Antarctica — a black, five-millimetre-long flightless midge that would be named Belgica Antarctica in honour of the expedition.

For the expedition’s ambitious leader, though, a new midge was not enough. Something far more notable must be accomplished to please the public back home — for instance, attempting to sail further south than anyone had ever done before. Keeping the decision from the crew and even the officers, de Gerlache ordered the captain to steer south, with the inevitable prospect of a winter trapped in the Antarctic ice:

Despite its dangers — rather, because of its dangers — an imprisonment in the ice would solve the Belgica’s glory deficit. It wouldn’t cost any more money, de Gerlache wouldn’t lose any men — at least not to desertion — and it would make for a dramatic story.

This reckless decision very nearly cost de Gerlache and his 18 men their lives, health and sanity. ‘In reality… we are as hopelessly isolated as if we were on the surface of Mars,’ wrote Cook, ‘and we are plunging still deeper and deeper into the white Antarctic silence.’ Soon the ship was stuck fast in drifting ice that over the next six months was to carry her on a crazy zigzag journey of hundreds of miles as the millions of tons that encompassed them were imperceptibly shifted and turned by unseen ocean currents.

Cook took photographs of his colleagues clowning around with penguins (de Gerlache leads an Emperor on a string, like a large dog) and went on long cross-ice expeditions with the gritty and professional first mate Amundsen, by far the most serious and experienced explorer among them. Amundsen, who would of course go on to beat Robert Falcon Scott to the South Pole in 1912, honed his survival skills among the shifting crevasses and iceberg ascents of the Belgica expedition.

Soon, however, the penguins deserted them and the polar night closed in — and Cook’s photographs of the icebound ship, exposed for one-and-a-half hours in moonlight, take on the quality of nightmare visions. ‘We are no longer navigators,’ wrote de Gerlache, ‘but a small colony of prisoners serving their sentence.’ The ice creaked and groaned incessantly as it shifted, pushing the ship up above sea level as the shelf thickened. Cook began to worry that the men’s minds would likewise come untethered and drift into fear and insanity. As the weeks of darkness stretched into months, screams echoed in the night. De Gerlache locked himself in his cabin. One sailor became raving mad and tried to escape across the ice. Cook ordered the malnourished men to stand naked in front of an open fire, and to eat raw penguin meat to combat scurvy. ‘Murder, suicide, starvation, insanity, icy death and all the acts of the devil, become regular mental pictures,’ Cook observed. The Polish geologist Henryk Arctowski put it more succinctly: ‘We are in a mad-house.’

As the sun returned, so did the men’s sanity. But the ice showed no sign of cracking. The half-ton of explosives brought for just such an eventuality turned out to be largely spoiled. Desperate, de Gerlache ordered the crew to literally saw for their lives, cutting through the thousands of yards of sea ice that separated them from the nearest open water with long hand-saws. The remaining unspoiled explosives were placed as close to the hull as they dared, ready to blast the thickest ice away. But to their despair, the shifting ice closed their hard-won channel, apparently condemning the Belgica and her crew to certain death from starvation and cold.

How did they make it out? You will have to read this splendid, beautifully written book to find out.

Comments