Is a 35 per cent pay rise reasonable? That’s the question which, rightly or wrongly, is at the heart of the junior doctors row.

We are part way through a 96-hour walkout which the NHS national medical director for England warned would cause ‘unparalleled levels of disruption’. Coming straight after the Easter weekend, coinciding with Ramadan and Passover, and lasting longer than any other walkout in NHS history, it has been timed for maximum impact. The health of sick people will be compromised: hernias will rupture, appendixes burst, cancer treatments will be delayed. But it will have subtler effects, too. One letter in yesterday’s Telegraph expressed dismay at the advice to ‘avoid risky behaviour’ during the strikes. The octogenarian author explained that ‘getting out of bed can be risky’, adding that ‘It saddens me that, on top of all the other anxieties that come with age, this avoidable one has now been added to the list.’

The government is up a creek without a paddle. In a 77 per cent turnout of junior doctors, 98 per cent voted in favour of strikes. The British Medical Association appears to have the public on its side. Believing doctors ‘deserve’ more, and seemingly willing to endure more misery and harm in order to support their claim, 54 per cent ‘strongly’ support the walkout, according to a recent Ipsos Mori poll.

True, many junior doctors often work antisocial hours under stressful conditions. Many are reportedly suffering ‘burnout’ post-pandemic, and they have seen a real-terms reduction in their pay over the past 14 years. The role can be difficult to square with family life and carries immense responsibility – though this was previously viewed as more of a privilege than a burden. There are concessions that the government could reasonably offer that don’t involve a 35 per cent pay rise, such as some degree of student debt forgiveness, which would have no immediate budgetary consequence and would not bake in much higher salaries.

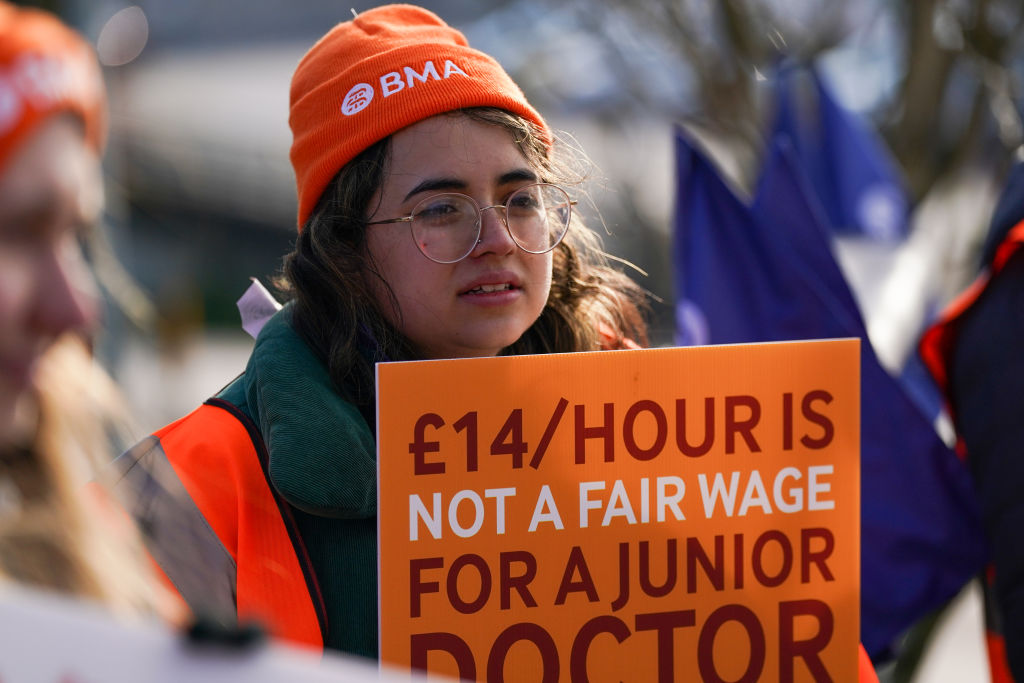

But the BMA, its members and supporters are at risk of overplaying their hand. They claim doctors are earning £14 an hour, equivalent to a door supervisor or teaching assistant. But this figure doesn’t include extra payments which can raise pay by up to a third, on top of the £29,384 basic salary for foundation year doctors in England (itself above the average graduate starting salary). And unlike bakers or baristas, there is consistent wage progression. The average annual NHS earnings of a junior doctor, including those working part-time, is £55,420, with the full-time equivalent average salary hitting £57,118.

Further, NHS employer pension contributions are over 20 per cent, compared with an average of 6 per cent in the private sector. NHS staff are in a privileged minority of workers who receive defined benefit pensions, which were all but wiped out in the private sector in the years to 2015. Regardless of how much NHS workers accrue, their pension income is guaranteed to a certain level calculated by a formula. This is tough on taxpayers.

As to the argument that doctors graduate with up to £100,000 of debt, unlike baristas or bartenders, that may well be correct, although most owe less. And remember that the taxpayer doesn’t spend over £200,000 subsidising the tuition, living costs and clinical placements of staff at Costa.

The fact that doctors and their supporters compare pay to that of other workers like this underscores a fundamental issue. Despite what the BMA may believe, all jobs are important. If they weren’t valued by some of us, they wouldn’t exist. Society needs hairdressers and security guards. It needs supermarket workers and millions of others who, in securing their own futures, contribute to the welfare of their fellow citizens in countless different ways. Those workers do not find it easy to repudiate their duties in the pursuit of a pay increase of up to £20,000 a year.

Think about this differently. The only reason we have such fierce and principled debate over doctors is because there is no functioning labour market in healthcare. We tie ourselves in rhetorical knots over doctors and nurses, but don’t have a national discussion over the pay of beauticians. The NHS’s rigid pay structures make it difficult to address specialty shortages and to reward those working hardest. They strip employees of the freedom to seek higher pay in other parts of the country where there may be demand but low supply.

And by attempting to control university recruitment, the government has failed to train new doctors in sufficient numbers. Only 9,500 places are available across the UK this year, meaning we do not have a sustainable supply without recruiting qualified doctors from abroad. Labour has said it would double the number of places and open up 15 new medical schools, but it too will come under pressure from a BMA resistant to any move that could force down doctors’ salaries. Government has also failed to contingency plan by, for example, bringing older workers out of retirement.

The NHS is a socialist relic with too many problems to list. But addressing the training, recruitment and rewarding of doctors, by expanding places and decentralising pay, should be a priority. It would, at least, put an end to the miserable holding pattern we now find ourselves in.

Comments