Politicians are said to campaign in poetry and govern in prose. In the case of Keir Starmer, he campaigned in the most uninspiring, plodding prose imaginable, and has now chosen to govern in what might politely be compared to a child’s first attempt at poetry. It is all word-vomit and incomprehensible mumbo-jumbo.

The country needed a leader who could make a passionate and convincing case for the importance of literature. What we got instead was an Arsenal obsessive

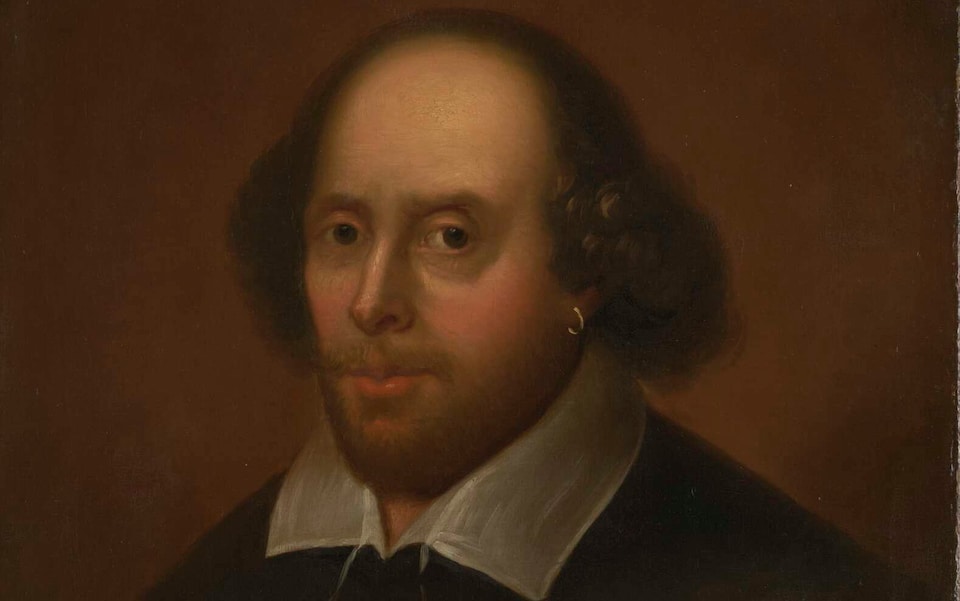

Still, this befits the character of a man who, according to reports, has overseen a steady exodus of portraits of key British figures from the walls of No. 10. First came down Margaret Thatcher, then Elizabeth I, and now, perhaps most egregiously of all, William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s place in British national cultural life is, for most literate people, without parallel, but it is politicians who have the most to learn from his work. If you remove all the tiresome buzzwords used about Shakespeare now – such as ‘accessibility’ and ‘universality’ – and go back to his actual plays, you are faced with one of the great treatises in how to govern and how to use power. In everything from the history plays to the tragedies – with even some of the comedies and problem plays chucked in – Shakespeare presents a guide to political life that is even more relevant to 2024 than it was in his lifetime. Any halfway literate prime minister would do well both to study the plays, and to venerate their author.

Starmer is certainly more than halfway literate, which is why it is an enormous shame that he seems to have adopted a persona that most would find both perplexing and disappointing. Get him on football – or, indeed, the oeuvre of Taylor Swift – and there’s no stopping the man. But if you ask Sir Keir questions about books, drama or literature, he seems to express precisely no interest. Before he was claimed by high office, he suggested that he knew Kafka’s The Trial back to front, and expressed admiration for James Kelman’s novel A Disaffection, a much-acclaimed stream-of-consciousness Scottish novel written in Glasgow dialect. But now, he seems to have forsaken such pursuits, even suggesting in his recent Desert Island Discs appearance that the book he would choose was ‘a detailed atlas, hopefully with shipping lanes in it… a big atlas, with real details.’ The point that Starmer was making was an unsubtle one. That as premier he would guide the country away from the isolation and confusion of the last 14 years of Conservative government, and turn Britain into a modern, outward-looking nation, rather than a forsaken little island.

In the first few months of the Labour government, nothing of the kind has happened, and so we must despair of both the accuracy and the philistinism of the metaphor that he chose to use. If Starmer had said instead that his favourite book was Kelman’s – or even the complete works of someone decidedly frivolous, such as the great PG Wodehouse – then he would have seemed like both a more genuine human being and a more rounded one. Instead, it’s back to technocratic posing and a sense that, somehow, reading is bourgeois and self-indulgent.

Sir Jonathan Bate recently complained that university students are reading less than they ever did before, and that those studying English literature have gone from being able to cope with three books a week to one every three weeks. He was criticised in some quarters for intellectual snobbery, but it is undeniably true that reading has become a dispensable luxury for many, and that the primacy of the written word has decreased immeasurably over the past decade, thanks to the rise of low-attention forms of entertainment.

What this country needed was a leader who could make a passionate and convincing case for the importance of literature, and its life-changing powers. What we got instead was an Arsenal obsessive. Good for football; bad for our country’s intellectual growth. Shakespeare, at least, had it about right, when he wrote in Richard III ‘Woe to that land that is governed by a child’. If Starmer could be prevailed upon to study the plays, he might find it desirable to bear his words in mind.

Comments