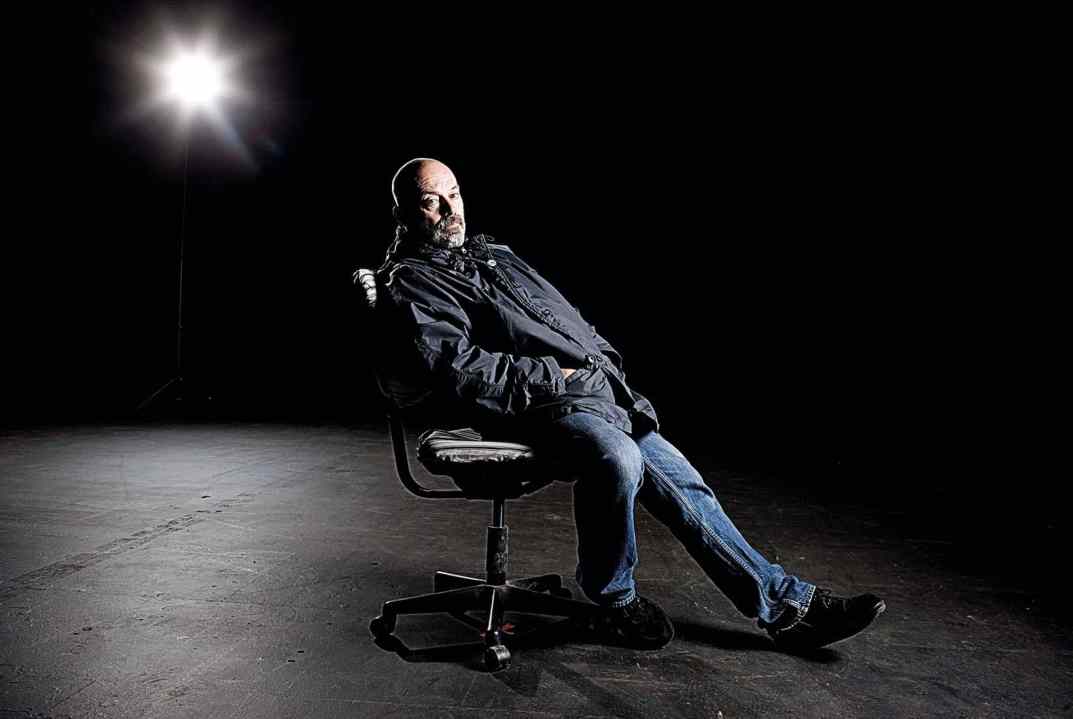

Keith Allen was cast in his latest show by Lady Antonia Fraser. He explains this odd circumstance when we meet during a break in rehearsals for Pinter’s The Homecoming.

‘I was asked if I wanted to do The Caretaker at the Theatre Royal Bath. And I said, “Yeah, I’d love to.” Then I had a conversation with Antonia Fraser who told me the script was licensed to someone else. She said, “Why not do The Homecoming instead – with you as Max?” And I said, “Yes.”’

Max is the thuggish head of an emotionally damaged Cockney family with criminal connections. His wife has died and he lives with his sons in a household that simmers with pent-up aggression. The plot is a quest to replace the dead mother with a powerful female figure.

‘It was always a dream of mine to play Max,’ says Allen. ‘A lot of actors want to play King Lear but I don’t think I’m up that ladder. Max has always been in my sights.’

The haphazard route that led him to the role is typical of his career. He doesn’t plan ahead and he’s unsure what he’ll be doing in a year’s time.

‘I have no idea. And I have to say I don’t mind. I’m coming down the hill now [he’s 68], so I don’t have those kinds of ambitions. I’m very happy where I am.’

Most biographies state that Allen made his stage debut in 1979 when he performed at the newly opened Comedy Store in Leicester Square. In fact he appeared earlier than that in Max Bygraves’s variety show, Singalongamax, as part of the chorus line. But he wasn’t supposed to be on stage. And he was stark naked.

‘I was squatting in Eaton Square at the time and it was very convenient for the Victoria Palace where I worked as a stage electrician. And I took umbrage with Max’s show. I knew my job was about to finish because I was off to France to pick grapes with my girlfriend. So I walked across the stage doing a Max Wall imitation. And the follow-spot operator fell off his stool. And the management made the rather stupid decision to drop the curtain. But I was in front of it. So it was just me and Max Bygraves. Afterwards he said to me, “You’ll never work in the theatre again.”’

As a youngster Allen was never drawn to the stage, and even now he talks of ‘proper acting’ as if it were something done by others.

‘I was the child of a naval man, a submariner, who lived abroad so you never put roots down in places. It was a wonderful childhood. It was great. I loved being a kid. And I never thought about acting. The only reason I went to drama college was there were loads of girls. When I left, I became a silkscreen printer so there was no ambition to go out there and be an actor.’

‘It’ll be interesting to see if people warm to Pinter’s piercing study of misogyny in this woke world’

He moved from job to job or, as he puts it: ‘You went to sleep as one thing and woke up as something else.’

He was a tyre-fitter, a butcher, a window cleaner and a coal miner at Brynlliw Colliery near Gorseinon.

‘God, I had so many jobs. But I always knew I was a performer in the truest sense of the word. I had a certain ability to – what would you call it? – command attention.’

He was living in central London, in the 1970s, when Tom Stoppard, Michael Frayn and Pinter himself were at the peak of their powers. Did he ever go and see their work?

‘I had no interest in the theatre whatsoever. I went to the theatre for the first time when I was 20 years old.’

A friend dragged him along to a production of Butley, by Simon Gray, at the Swansea Grand Theatre.

‘The lead actor was James Bolam, from The Likely Lads, and I’d seen him on television. And I just couldn’t believe I was in the same hemisphere as a bloke I’d seen on TV. I was pathetic. I was genuinely shocked that there was a man there in front of me who I’d seen on telly. I really could not believe it. And that was my introduction to the theatre. Nothing to do with understanding the play, just, “Christ. He’s been on telly. And I saw him.”’

Did it cross his mind that it might be him one day?

‘No. Never. Not at all. Funny, isn’t it?’

Though he had no interest in drama, he found himself in ‘the incredibly privileged position’ of watching the cream of fringe theatre at the ICA on the Mall. The ICA’s director wanted to expand the repertoire to include avant-garde drama companies, and Allen happened to be the in-house decorator.

‘I was painting the galleries at night when the exhibitions changed over. And I met two guys who were actually living in the ICA. One was Bill Drummond [the founder of KLF] and I got to know them.’

Allen was offered a job as stage manager.

‘I then watched virtually every single touring fringe theatre company in the country. And that had a real effect on me.’

The programme included the experimental absurdist Ken Campbell, whose sets were built by Allen and Drummond.

‘And Ken cast me in Illuminatus! as a waiter. It opened in Liverpool.’

This turns out to have been Allen’s debut as a paid actor.

‘It was a non-speaking part. Basically I opened the door and went across the stage. Just an entrance and an exit but I turned it into a virtual ballet of my own.’

Did he get big laughs?

‘Oh yeah. Yeah, it was great.’

Occasionally he overdid the ‘ballet’ and got yelled at by Campbell in mid-performance.

As he prepares to star in The Homecoming, Allen is concerned about the sensitivities of contemporary theatre-goers.

‘It seems to me that people are stepping out of two years of Covid. And they want knickers and songs. But a piercing poetic analysis of misogyny? That’s a tricky one to get your head around. It’ll be interesting to see if people warm to it in this “woke” world. Especially for younger audiences. I think they’ll have a lot more difficulty engaging with it than an audience in the 1970s.’

Because it’s a period piece?

‘Because of the things it’s about. Suppressed violence, male violence and the position of men in a male household. And the introduction of a woman and how they deal with her. But as far as I’m concerned she’s the winner by a metric mile.’

The play ends with a young woman being welcomed by the all-male household but it’s unclear whether she plans to exploit the men or vice versa. Audiences have found it bemusing or downright incredible.

‘I think that’s perfectly in keeping with Harold’s intentions,’ he says.

And what are his intentions?

‘Well, you just have to work it out for yourself. I don’t think you could ever answer that question.’

The Homecoming is at the Theatre Royal Bath from 30 March until 9 April, and touring until 21 May.

Comments