If they have any sense – a proposition I will test later – officials from Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Plaid Cymru will be beginning meetings to work out a pact for the 2023/24 election. If they do not agree to a joint programme, there’s a good chance that Conservatives will be in power until a sizeable portion of this article’s readership is dead.

The next redrawing of constituency boundaries in 2023 is almost certain to favour the Conservatives, adding ten seats to the already unhittable target of 123 constituencies Labour needs to win to govern on its own. There’s a possibility that Scotland could be independent by the end of the decade, and that ought to terrify anyone who wants to stop the rest of the country becoming a one-party Tory state.

In other respects, the rolling costs of Brexit and Covid, the institutionalisation of chummy corruption in Downing Street, and the slowest productivity growth in 120 years are ensuring that the 2020s will be a disastrous decade that could end with Britain as a northern version of Italy but without the style. Does the centre-left really want to sit it out?

Naomi Smith of the Best for Britain campaign group, and one of the most realistic thinkers on the liberal left told me:

‘Given the impending boundary changes, Labour’s got one last chance to do the right thing for the majority of voters who didn’t back this nativist government. Its only path to victory is to work for a coalition government that can change the voting system.’

To understand why cooperation is essential you need to grasp how awful Labour’s position is

A pact would mean one centre-left candidate in each English and Welsh constituency, who would either be the sitting MP or the representative of the party that came second behind the Conservatives, running on a common platform.

To understand why cooperation is essential, you need to grasp how awful Labour’s position is. If I had the power, I would insist that an emphasis on the near impossibility of Labour returning to office on its own ought to begin all the ‘whither the left’ articles that fill liberal comment pages today. To win a majority at the next election, Labour needs a swing of ten per cent or more. I am not saying it cannot happen. But I cannot begin to imagine the circumstances in which it might happen.

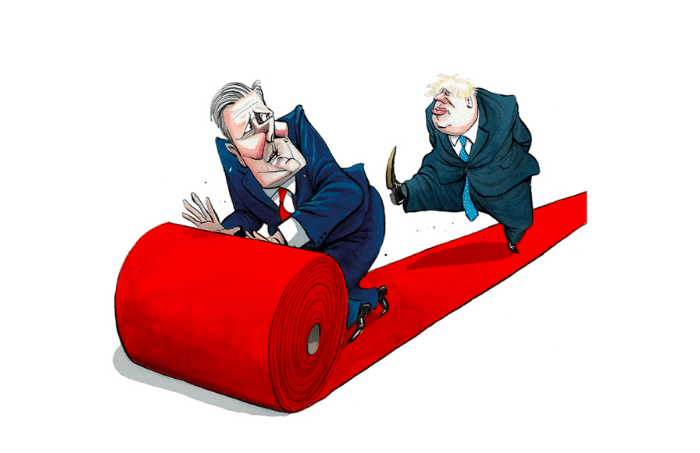

Victory appears impossible because Labour faces simultaneous political, cultural and national crises. Keir Starmer is a perfectly adequate leader. I have no doubt that thousands of lives would have been saved if he, rather than Boris Johnson, had been prime minister during the Covid pandemic. But Labour’s troubles require a politician of genius to solve. Starmer isn’t a genius, and once again my imagination fails me as I try to picture what a Labour leader who could resolve its troubles would even look like.

The war between left and right in the party has become a war without end. I always believed that communists or post-communists and social democrats cannot and should not be in the same party, and so it is proving. The worst electoral defeat since 1935 has not made the leading figures on the left abandon their tactics and cause. There has been no repeat of the impressive unity American progressives forged against Trump.

Perhaps Labour activists do not believe in their hearts that Johnson is as dangerous as Trump, despite the rhetoric to the contrary. The truth remains that each side in Labour’s civil war hates the other more than it hates the Conservatives. Labour will waste its energies on internal feuding for as far ahead as I can see.

Meanwhile there is widespread denial about the scale of the liberal-left’s cultural crisis. Many maintain the pretence that culture wars are fought only by the right-wing equivalent of Stalinists as they try to force the National Trust into airbrushing the truth about slavery from history. Alternatively, they hold that, because most people do not have the faintest idea what ‘woke’ means, the culture wars are phoney wars that pass the bulk of the population by.

The truth they duck is that two culture wars are being fought now. Both make the task of returning a Labour government harder. Within the liberal-left, there is largely suppressed resentment at the silencing of gender critical feminists.

The censorship within liberal institutions – by which I mean the 250 government departments and public bodies, and 600 or so private companies and charities that allow Stonewall to shape their workplace inclusion policies – is so effective it hides the anger of all but the bravest women. Conservatives MPs tell me they are noticing a pattern they first saw with progressive Jews. Women constituents are telling them that, although they have not become Tories and still deplore Brexit and Johnson, they now regard a Conservative government as the least dangerous option.

Meanwhile Labour, like centre-left parties across the developed world, is becoming the party of the educated and ethnic minorities. In 1987, almost four-fifths of Labour’s support came from working class, or C2DE, voters (7.8 million out of ten million). By 2019, that number had almost halved, to 4.1 million. In contrast, its middle class vote almost trebled, from 2.2 to 6.2 million.

Although you cannot click on a news site without hitting a piece on how Labour must appeal to lost voters in Red Wall seats, there are cultural constraints on how far it can go. Suppose it were to propose hunting down the 600,000 or so migrants who are here illegally. Or say that it is entirely happy with the disastrous Brexit deal Johnson has hung round this country’s neck. It might play well in lost seats in Tyneside and Lancashire. But a part of Labour’s liberal support would simply walk away.

Most serious of all is Labour’s national problem. The Tories and Liberals can trace their origins back to the English civil wars of the 17th century. Labour is a British party born and bred in the UK. Its collapse before Scottish nationalism, not only deprived it (and the country) of Scottish politicians of the quality of John Smith, Gordon Brown and Robin Cook but created an identity crisis.

How does Labour stop itself unravelling as the country unravels? It might offer a middle way between nationalism and the status quo and propose home rule for Scotland, but the Conservatives would run an English nationalist campaign, as they did in 2015, and accuse Labour of being in Scottish nationalist pockets. If it concentrates on lost Red Wall seats, Scottish nationalists will accuse it of being an English party.

The only way out for Labour and everyone else on the centre-left is for work to begin now on a progressive alliance to stop the Conservatives in England and Wales. A Best for Britain analysis from January showed that Labour could win 70 more seats if it was prepared to put aside its absolutist refusal to work with others. The idea should not be controversial: Nigel Farage entered a de facto pact with Boris Johnson when he withdrew Brexit party candidates from Conservative seats at the last election. He may well cut a similar deal in future.

I fully understand Labour fears that, if electoral reform comes, the party will split. But frankly the stakes are too high to get lost in partisan calculations. It is about time for all who oppose conservatism to stop the navel gazing and ask what they need to do to win.

Comments