If you want a monument to the winner-takes-all conservatism developed by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan and reduced to absurdity by George Osborne and Donald Trump, look at the pulverised public realm and browbeaten citizenry around you. The project is a wreck. And I have seen few better examinations of its ruins than The New Serfdom, published tomorrow by the Labour MP Angela Eagle and Labour researcher Imran Ahmed.

Arguments have their time. The self-confidence with which Eagle and Ahmed take apart the ruling ideology ought to be a sign that Britain is ready for a reforming government that can ease the pain and remedy the injustices the Conservatives have presided over. Yet the authors cannot bring themselves to admit that, if radical change comes, it will be a radicalism that destroys them and their ideals. Think about what is not said in this excellent book and you begin to understand the extent of Labour’s tragedy, and Britain’s tragedy too.

The title is a play on Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom, the foundation myth of modern conservatism. George Orwell reviewed it in the Second World War and saw at once what was wrong with Hayek’s call to defend freedom by slashing back the state and taxation. The notion that free markets are free ignores their tendency to monopoly, so striking today in the dominance of Google and Facebook. The notion that taxation is state tyranny means many must endure the tyrannies of poverty and neglect. Again, look around you, and see how the destruction of the power of organised labour and Osborne’s tax cuts have not produced a new age of entrepreneurial success. Real wage growth has been stagnant for a decade. The economy has never ‘gone back to normal’ after the 2008 crash. Normal now for the British is to watch spluttering growth while waiting for the next recession to knock us back and the next wave of technological change to enrich the already wealthy.

The power of capital over labour means our high employment rate is built on insecure work with all the physical and mental health illnesses it brings (Fifteen per cent of the workforce is now self-employed; six on short-term contracts; three on zero hours contracts.) The authors are adept at deploying information that ought to become part of the common sense of the times. If the proceeds of growth had been fairly shared since 1990, wages would be 20 per cent higher in Britain (and 40 per cent higher in the US). George Osborne would have abolished the budget deficit by this year, if he had not cut taxes, including the taxes of the wealthiest.

As for the public realm, I defy anyone except the most purblind conservative to deny the evidence of its disintegration. The health service has a chronic shortage of doctors and beds. Local government is unable to maintain the roads, care for the mentally and physically ill, or begin to cope with the care needs of the aging baby boomers. The police can’t catch criminals. The army can’t fight wars. As Orwell said of Hayek, ‘The trouble with competitions is that somebody wins them’. It is all too clear who has won and who has lost in Britain today.

Twice now in recent history the need for an opposition has appeared to vanish. I wrote at the height of Blair and Brown’s rule that radical time travellers from late Victorian Britain would see every cause they campaigned for had triumphed: universal health care and education, the relief of poverty, votes for women – along with new feminist and gay rights campaigns that had barely occurred to their generation. Anthony Crossland’s The Future of Socialism expressed much the same thought in the early 1960s. The Conservatives had accepted the welfare state and the NHS: surely, the old struggles were over.

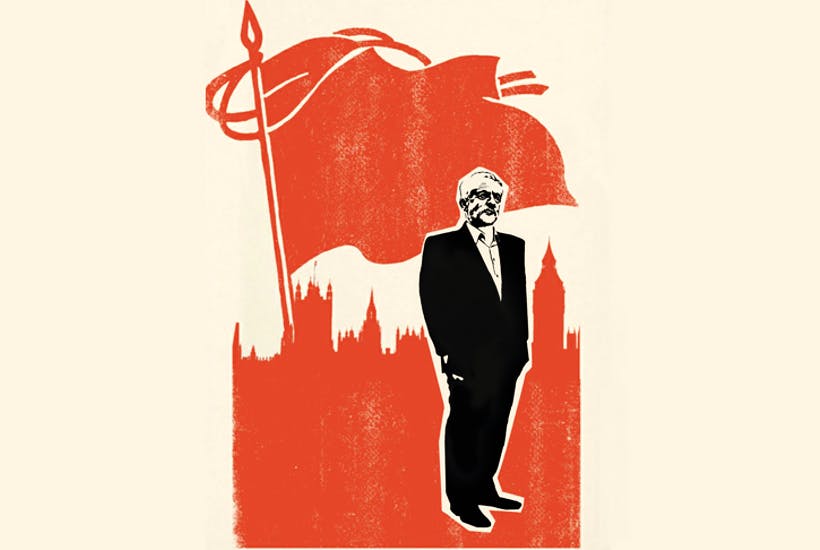

The experience of Conservative governments provides a reason to return to old fights. By rights, Angela Eagle and scores of other competent Labour politicians should be preparing to rescue Britain. But instead of being members of a reforming government in waiting, they are spectators as a far left animated by a hatred of the West and fascistic conspiracy theory takes over the party. I don’t want to overanalyse the Corbyn movement, and worry too much about which box of left-wing thought it fits into. You only have to look at candidates who endorse anti-Semitism or suggest the murder of Jo Cox was a false flag operation, to dispense with political science and conclude that a portion of its supporters appear mentally ill.

Eagle may not survive. The remnants of the Militant Tendency are strong in her Merseyside constituency and she challenged Corbyn’s leadership. As for Ahmed, he ought to be an MP and has the intellect to be a cabinet minister in the future. As it is, I struggle to see him finding a winnable seat.

Yet search through this book and you find only once do the authors mention Corbyn’s name, and then in passing. Their embarrassed silence contains a warning.

The Labour establishment made a mistake when it decided that its main argument against the far left was that it could not win an election rather than it should not win an election. It ought to have said that either course leads to a swamp. If the far left keeps the Tories in, then the rich will continue to run riot and the country will continue to sink. If it wins power, then its behaviour in government will damn radical politics for decades. What is Corbynism? Above all else, it is a scandalous wasted opportunity.

Comments