If you’re looking for an early example of Tom Stuart-Smith’s work, you’d have to go to a car park to find it. The now world-famous landscape designer started his career doing ‘awful supermarket projects’ where ‘landscape was perceived as just something they kind of had to do’. This was in the 1980s: today, if you want to see a Stuart-Smith landscape, you can go to St Paul’s Cathedral, where he has designed a public ‘reflection garden’, the walled garden at the Knepp Estate, or the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield, where sculptures sit among naturalistic sweeps of grasses and perennials. (He recently unveiled his proposal for the Queen’s memorial garden, featuring a huge bronze cast of an oak tree and a ‘sonic soundscape’ of memories of the late monarch – but Norman Foster beat him to the commission.) He is also about to transform London’s Millbank with a new landscape for Tate Britain and is designing a huge new public garden in Edinburgh – the first new public garden to appear in the city for 200 years – on the site of the old Royal High School on Calton Hill. He’s received eight gold meals and three ‘best in show’ awards at Chelsea. That’s not to mention the numerous private gardens that he’s designed around the world.

He is in other words one of the big names of landscape design, but interviewing him in his own garden at Serge Hill in Hertfordshire is quite unsettling because despite all these medals and famous public gardens, Stuart-Smith is perfectly happy to talk about all the times he’s got things wrong. He’ll mention a tree he included in the Hepworth garden, for instance, and say that it is struggling because he hadn’t anticipated that the climate would be so wet in Yorkshire. This is not what I am used to. You can interview a politician for hours without them admitting they’ve done a single thing wrong – even when an official report has listed their failings. The stakes are rather lower for a mistake in landscape design, but then again planting a tree that fails isn’t cost-free either: mature specimens can be hundreds or even thousands of pounds. Why does he feel he can afford to be so honest? ‘I was brought up by a judge,’ he explains with just the sort of diction you’d expect from the son of a judge. ‘And I also know that I personally learn more from my mistakes than anything else. And so I think if there’s half a chance that somebody else might learn from them as well, then that’s a good thing. Everybody in our game knows that they make mistakes. I’m just not particularly fussed about owning up to them.’

He explains how his style has evolved since he created his own garden. He wouldn’t have such a structured, arts and crafts-style set of ‘rooms’ divided up by formal hedges if he were starting out now. As we wander through a prairie area on the site, I ask if he agrees with the many people who describe him as a naturalistic designer. ‘I suppose I am. I mean, look at this,’ he says, gesturing to the sweeps of perennials punctuated by loose, unclipped shrubs and young trees. ‘I am interested by what point we let nature take over, and in articulating that meeting between the human and the natural.’ But he insists that there isn’t such thing as a ‘Tom Stuart-Smith garden’. He’s a ‘contextualist’. He explains: ‘We as designers are led by the frame and the circumstances in which we are working. If I was making a garden for a 13th-century castle, I wouldn’t say, well, I’m going to put a Tom Stuart-Smith garden in. I never think of it like that. How can I make the place – I like Mary Keen’s expression of this – make a place more itself. Bring out its true character.’

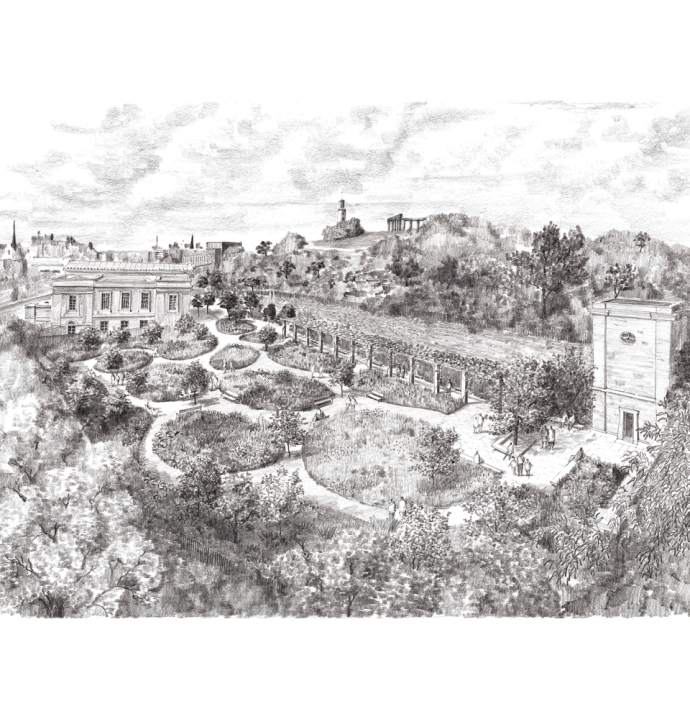

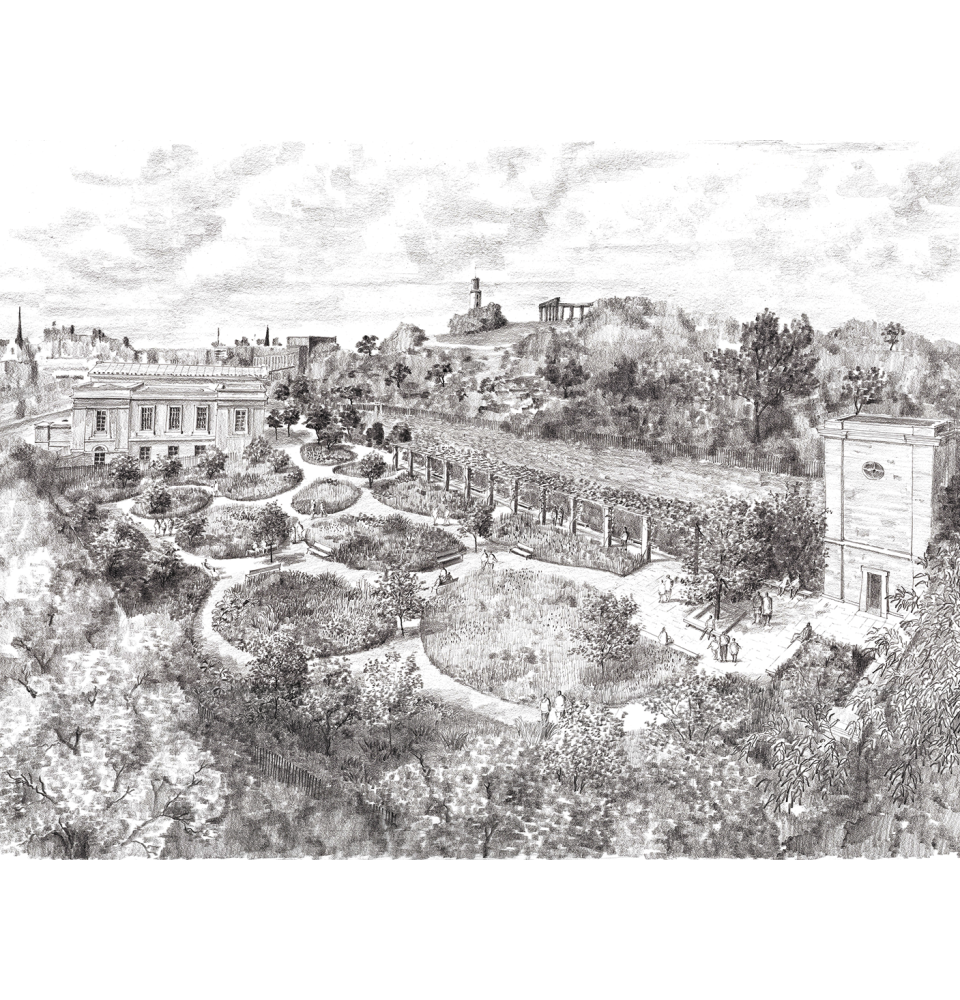

Perhaps that is why part of his Edinburgh project includes a large garden planted entirely with Scottish native plants, to bring out the true character of that site. It is on the same dark brown basalt as Arthur’s Seat, and Stuart-Smith is hoping to leave some of that rock exposed through the garden. Does he not worry that a purely native planting palette might be too limited, and frankly too bleak in winter to excite the general public? Britain’s flora is unusually meagre compared with the North American or Himalayan habitats that many popular garden plants hail from. ‘Well, Molinia [a native moor grass which turns a beautiful yellow in autumn and winter] looks beautiful in winter. But there’s not going to be a vast amount of evergreen other than little bits of heather, vacciniums [bilberries and cranberries], of course, which, even if they’re not keeping their leaves, have bright green stems. We’ll have a bit but not too much gorse, too. So all that kind of acid yellow.’ In the summer, there will be the rich pink-flowered sticky catchfly, Silene viscaria, which grows wild on the rock faces of Arthur’s Seat but has become critically endangered in Scotland, and whorled Solomon’s-seal, Polygonatum verticillatum.

As with all of his designs, Stuart-Smith has produced his vision for the Edinburgh garden in pencil. Other designers now parade their designs using ultra-realistic CAD visualisations, but these hand-drawn gardens have become Stuart-Smith’s calling card, a piece of fine art with a garden thrown in. They take him about six hours each, he says, though if he chooses to imagine a garden in winter, it takes longer because the naked trees are more complex.

Stuart-Smith is perfectly happy to talk about all the times he’s got things wrong

He is also intensely interested in the lives of the plants he designs with – more than many landscape architects, who are often not known for their botanical knowledge. To rectify this, Stuart-Smith set up something called the Plant Library next door to his home, buying some land from his sister who owns the neighbouring plot. The library grew from a twin desire to set up a community gardening project and also to educate other designers, including those working in Stuart-Smith’s busy studio of around 20 staff, about how plants grow and how they might look at different times of the year. It’s impossible to create a catalogue library of plants, so the selection seems to be based largely on ‘plants that we like or are interesting, or rare, or might be difficult but beautiful, or occasionally you get a genus that you think is really, really great and not so widely known’. That mix is then laid out in a grid across the site, which happens to have two different soils in it: light sandy loam at the top, ‘solid clay’ at the bottom. It’s so solid that they’re now creating a swamp garden in one corner, which currently looks ‘embarrassing’ but will soon be filled with bog plants.

Some of the beds have been made with 10cm of sand, which is currently the fashionable planting medium of choice for garden designers, along with crushed concrete from buildings. Designers love both substrates for their low nutrients. This means fewer weeds, and plants that take care of themselves rather than needing endless staking because they have become too blousy. Not everyone is a fan of this vogue. The phrase ‘sand is the new peat’ keeps cropping up horticultural circles, as sand has to be extracted from somewhere. Stuart-Smith disagrees: ‘Well, you don’t have the carbon knock-on of extracting peat. But if you accept you’re going to want to plant with some kind of mulch of some sort to help with weed control, what do we mean by sustainability? I would say that if this project is made more viable in terms of its aftercare by doing this technique, then that’s a pretty good measure.’

Weed control brings us onto another touchy subject in gardening: the herbicide glyphosate. Stuart-Smith has used it, notably on the rock garden at Chatsworth, where he felt the carbon footprint of digging out brambles, bindweed and other perennial weeds would be much worse than the impact of a weedkiller like Roundup. ‘It’s pretty filthy stuff,’ he admits, ‘I would say if you use it as a gel on very, very intractable weeds like bindweed, very, very small amount, the amount you are using is so minute, I wouldn’t personally have a problem with that, but I think continued repeat use is just not on, like on maintaining your paths. That’s got to be nuts.’

‘But,’ he adds – very much the son of a judge – ‘by and large it would be a good thing if glyphosate was banned because it does a lot more harm than it does good. You’ve got to take a big picture view, not use special pleading.’

Comments