One of the things Philippe Sands clearly remembers from his grandparents’ Paris apartment — a rather sombre, silent place — is the lack of family photographs. There’s a single, framed, unsmiling wedding photo, and that’s all. There is no mood of bittersweet nostalgia, there are no nods to memory or history. Where did his grandparents come from? How did they end up as these people, whom he knew only towards the end of their lives? Retrieving that history, that deliberately unremembered story, is the beginning of Sands’s task in this remarkable book.

Generically speaking, the story is familiar enough. Leon Buchholtz — Sands’s grandfather — was born in what was then Lemberg, in the very heart of Europe. As the first world war began to take its toll on the family, young Leon and his surviving family moved west (like so many others), to Vienna. He married Rita, their marriage witnessed by her brother, Wilhelm, a dentist. Leon ran a liquor store. Then came the Anschluss; some Jews left, some remained. Leon was one of those who left. But his wife and their infant daughter — Sands’s mother — stayed behind. Why? Rita would only leave on 9 November 1939, the day before the borders closed. Sands’s two maternal great-grandmothers were soon on a train east, to Theresienstadt.

Eventually Leon and Rita settled in Paris, where he was involved with the French Resistance, sending packages to the camps and ghettos in German-occupied Poland. Among the documents Sands examined in his research were the postal receipts for these dispatches. For the rest of his life, Leon would keep a great deal of evidence — some of which ended up with Sands’s mother, Ruth, and another trove in a plastic shopping bag with his aunt Annie — but he did not speak of this time.

Sands is tenacious in his investigations, however. He examines construction plans and permits; he conducts careful analysis of photos (he is a lawyer, after all, a professional scrutiniser of evidence); he consults school registers and cadastral records, undergoes DNA tests, visits significant places (sometimes wandering around Lemberg with three different historical maps).

And he has a taste for detail. Does it matter that Wilhelm was a dentist? That aunt Annie’s stash of letters was in a plastic bag? It does. The detail makes for vivid reading, but it also serves posterity; it is memorial. We all know there are countless stories a bit like Leon’s. My family has them, and so perhaps does yours. But that very countlessness is the most grotesque kind of shorthand, especially at a time of such extreme, mechanised dehumanisation. Think of prisoners in concentration camps, all indistinguishable in their striped uniforms, their heads all shaved; think of the ghetto Jews, each distilled to the presence of his essential, defining yellow star, the four million Jews and Poles murdered in Polish territory. The things that make the stories individual should matter. The dignity is in the detail. Sands carefully assembles one such story.

But Leon Buchholz is only part of it.

Dr Julius Makarewicz was a professor of law at the university of Lemberg. His students in 1917 included a young man by the name of Hersch Lauterpacht, intelligent and intense with a striking sense of humour. Lauterpacht had been born in Zólkiew (where Leon’s family was from, too), and lived in Lemberg from his teenage years. Lauterpacht’s courses at the university included one on ‘optimism and pessimism’, while Makarewicz taught him Austrian criminal law. He, too, would move to Vienna; and 15 years before Leon would flee to Paris, Lauterpacht made for England. In England he would develop his ideas about the formation and enforcing of international law, regardless of state jurisdictions. ‘The well-being of an individual is the ultimate object of all law,’ he wrote. He remained deeply engaged with the situation in Poland, and kept up a correspondence with his family, but never spoke to his son of his own time there. More silences.

In time Lauterpacht would come to be a professor of international law at Cambridge, and a friend and adviser to the US Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, an ally against American isolationism and eventually chief US prosecutor at Nuremberg. It was in a conversation with Jackson that Lauterpacht first used the phrase ‘crimes against humanity’.

But back to Lemberg and 1920 — by which time the winds of change had blown once again. Lemberg had become Lviv, Lviv became Lwów, washed over by successive imperial tides. Professor Makarewicz was still teaching at the university, though his course was no longer in Austrian but Polish criminal law. And this year — so soon after Lauterpacht had graduated — his students included another remarkable young man, Rafael Lemkin. Following an influenza pandemic, he had taken an early interest in the destruction of groups, which came into horrific focus when over a million Armenians were murdered in the summer of 1915. Like his near-contemporary, Lemkin was to develop his own theories of international law, his focus being on group victims. He called this ‘genocide’. These were acts ‘directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of national groups’. (Lauterpacht did not approve of this concept.)

In the autumn of 1945, when the Nuremberg indictment was published, it would include two groundbreaking new notions: Lauterpacht’s ‘crimes against humanity’ and Lemkin’s newly coined ‘genocide’. The difference between these two was fundamental, essential — is the focus on the individuals or the group? — but they had much in common, not least the peculiar coincidence that their originators, though not known to each other personally, had developed their thinking in the very same classroom, under Professor Makarewicz. Leon’s grandson, this book’s author, would grow up to be a human rights lawyer, too.

So, we have three men — Leon, Lauterpacht and Lemkin — each of whom spent some of their early life in Lemberg, and the grandson of one, our author, following the threads that connect them. But there is one life left to tell.

Hans Frank was also a lawyer. But he was Hitler’s lawyer. He helped to draft the Nuremberg decrees, stripping Jews of the rights of citizenship, and he argued for ‘non-interference in the internal affairs of foreign states’, and for a legal system whose protections for ‘national community’ — over individual rights — were paramount. He also spent five brutal years in charge of German-occupied Poland, with both Lauterpacht’s and Lemkin’s families suffering under his rule. A cultured man, Frank liberated countless works of art from Polish collections (a ‘protective’ measure, apparently). Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Lady with an Ermine’ hung in his private offices. ‘This is how you should comb your hair,’ he told his young son, Niklas.

As a boy, Niklas Frank had been taken to visit the Kraków ghetto. Unable today to love or forgive his father, Niklas accompanies Sands to Courtroom No. 600, where his father was tried. ‘This is a happy room,’ he declares, ‘for me, and for the world.’ But Hans Frank, the ‘Butcher of Warsaw’, is now ‘Niklas’s father’. (If you thought it was impossible to create emotional complexity around an arch-Nazi, you were wrong.) Alongside Niklas Frank, Sands also meets Horst von Wächter, son of Otto von Wächter, the governor of the district of Galicia — but Horst tries to find ways of exonerating or mitigating his father’s guilt (‘I must find the good in my father’) — he was operating only as part of a group, part of a larger system, after all. Sands’s book is about individual vs collective victimhood, but it’s about individual vs collective guilt, too.

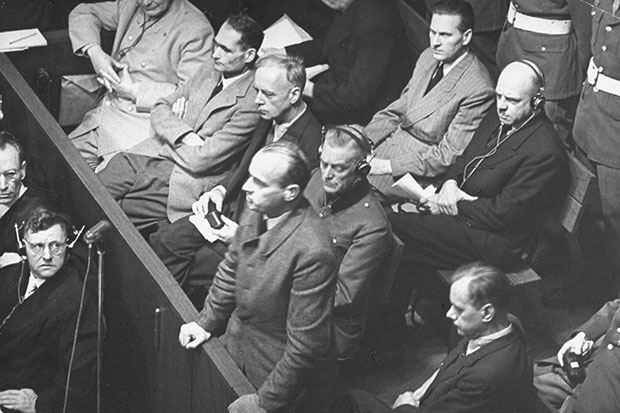

Which brings us — the key participants now in place — to Nuremberg. Frank’s name appears on the list of 24 defendants; and the charges referred to in the indictment, in autumn 1945, include both ‘crimes against humanity’ and ‘genocide’. When Frank took the stand, Lauterpacht was in the room.

The trial and judgment at Nuremberg would be the first test of Lauterpacht and Lemkin’s legacies, and Sands’s extensive account of these manages to be both complex and gripping. But the book’s implicit argument is for the longer legacy of these great legal ideas, each of them developed by one man.

East West Street is a fascinating and revealing book, for the things it explains: the origins of laws that changed our world, no less. It’s also a readable book, and thoughtful, and compassionate. Most fundamentally, though, it’s a book that tells a few individual human stories that lie behind the world-changing ones. That storytelling isn’t redemptive — what could be, in this context? — but it confronts all those silences and challenges them. That challenge makes it an important book, too.

Comments