Elaine Sciolino was advised to find herself a French lover for research purposes; as far as it’s possible to tell, she didn’t, but this may be the only stone left unturned in this extraordinarily thorough study of French seduction.

Elaine Sciolino was advised to find herself a French lover for research purposes; as far as it’s possible to tell, she didn’t, but this may be the only stone left unturned in this extraordinarily thorough study of French seduction. Sciolino, a correspondent and former bureau chief for the New York Times, has managed to turn the mysterious process of seduction into a thesis.

Armed with a seemingly unassailable volume of evidence, she argues that life in France is about process rather than results, charm rather than truth, pleasure rather than toil. She has a broad definition of seduction:

The tools of the seducer — anticipation, promise, allure— are powerful engines in French history and politics, culture and style, food and foreign policy, literature and manners.

She meets France’s grands séducteurs — not just the skirt-chasers, but also the purveyors of other kinds of pleasure — chefs, diplomats, lighting engineers, underwear designers, gardeners, her butcher. Some of the most enjoyable parts of the book are these meetings with people who will go to any lengths to create a perfect product. ‘Seeing him transform milk into Camembert is like watching a dancer,’ she writes of a Normandy dairy farmer. In Grasse, she tours the farm where they grow flowers for Chanel. The farmer

knows when a rosebud is full and with a tiny movement of his finger can coax it open. He knows when his jasmine plants are ‘under stress’ and need more water.

He needs to: it takes seven million jasmine flowers to produce a kilogramme of the concentrate used for scents.

Captivating descriptions of sausages, petals, peas and lace give the sense that appreciating these pleasures is a skill that should be taken seriously. Sciolino is taken aback when a food critic tells the chef Guy Savoy that his carrots are sublime. ‘I couldn’t quite believe it and said so. “Carrots are carrots,” I said flatly.’ There follows a lesson in carrot eating, and in the end Sciolino can’t quite resist agreeing:

I don’t know whether it was the food on the plate or the excitement in Savoy’s voice that made the carrot experience memorable, but it helps explain why the French don’t eat alone. It is simply too delicious an experience to keep to oneself.

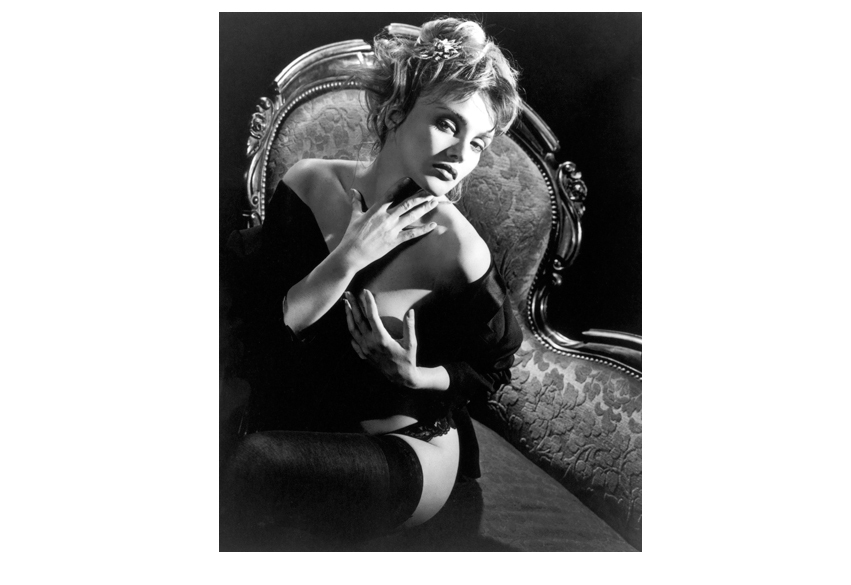

When it comes to sex, Sciolino manages to avoid repeating the clichés. The singer and actress Arielle Dombasle comes out with unsettling, darkling knowledge: seduction is war, nudity is a violent thing, do not be naked in front of your husband or he will not buy you lunch.

Sciolino has an engaging tone, and is happy to shrug in incomprehension rather than breathlessly accept whatever the husky voices are telling her — Dombasle, she says, was just too sexy for her. In another scene, the philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy and the journalist the late Françoise Giroud solemnly discuss the difference between a charmer and a tease — a charmer, says Giroud, is engaged in ‘offering oneself and holding back, giving in and remaining aloof, an odd mixture of playfulness and reticence.’ Sciolino doesn’t buy it: ‘Sounded like a tease to me.’

The French are unapologetic about extra-marital sex. The writer Jean d’Ormesson is quoted advising an American reporter against it:

We cheat in so many, many, many hundreds of years that now you know how to manage. Don’t try. It’s very difficult…you have to be French.

On smiling, on diplomacy, on make-up and privacy: the book is full of amusing attitudes and anecdotes. Occasionally you feel that the ‘experts’ are delighted to light up a Gauloise and give her a theory, off the top of their heads, but they’re usually enjoyable.

It’s straight reportage. Sciolino quotes without passing judgment on the unfaithful husbands or the lecherous old presidents. She asked members of an elite women’s club whether they felt undermined by sexual politics. Nearly all of them said they used seduction as a weapon, as part of a game of power, as a tool to get things done. Things like this cast some doubt on the efficacy of seduction — the gender statistics are not good in France, and perhaps Sciolino gets a little carried away by the romance of her subject. She argues that many of France’s problems demonstrate a failure of seduction, without engaging in any feminist angst about the downsides.

Still, it’s rather a relief that she doesn’t, and the subject is irresistible: you’re being pulled into a rarefied world where the lights are always dimmed, the people always beautiful and the carrots always sublime. If it’s not a complete France, it’s a wonderful side of it that’s certainly worth visiting.

Comments