Benghazi

On the surface, at least, these are youm maasel, or sweet days, in Benghazi.

Benghazi

On the surface, at least, these are youm maasel, or sweet days, in Benghazi. Strolling along the seafront I pass the exuberant crowds who have set up camp in Liberation Square. There are carpets laid out for prayers and around them, flags and trinkets coloured in the distinctive red, black and green of Libya Hora — free Libya. Around the square triumphal marches take place and from a ramshackle platform excitable rebels deliver speeches about imminent victory. Two colonels, both called Ali, have set up shop on the Corniche in front of an old Mig fighter. Their stand displays exciting paintings of engagements between the free Libyan air force and troops loyal to Colonel Gaddafi.

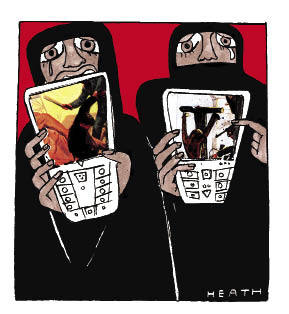

But Benghazi could easily return to youm basal — onion days. Even amid the celebrations, the tragic cost of the battle is visible. The mothers of the fallen sit in the shade under a makeshift tent in front of the courthouse holding pictures of their loved ones. The hospitable nature and cheerful countenance of the average Libyan hides (at least initially) the concern and grief over lost relations, but every day more stories of appalling atrocities emerge, backed up by graphic mobile-phone footage. It’s hard to watch. It’s hard to think of the crimes against history being perpetrated, too. The rebels say that Gaddafi’s forces have begun to shell the ancient oasis town of Ghadames. I went to Ghadames when I was last in Libya 12 years ago with the travel writer (and Spectator contributor) Justin Marozzi. We began in the city and bumped along for 1,500 painful miles by camel. According to Mohammed Ali, the guide mentioned in Justin’s excellent South from Barbary, ‘It is a very old city — 2,000 years old or 5,000 or 12,000.’ Whatever its age, Gaddafi’s shelling of this World Heritage Site is heartbreaking.

The greatest worry here in Benghazi is that the National Transitional Council is running out of money. The Libyan rebels are grateful for the Nato campaign, although there is some confusion about the scope and objectives of the mission. They are also grateful for David Cameron’s help in getting UN resolution 1973 passed so speedily. But Britain has not yet been able to solve the problem of cash, and in seven days, the council will be broke. This can be solved: De La Rue, the banknote company, should be permitted to release the 1.4 billion Libyan dinars (approximately £700 million) of printed cash that is sitting in Britain. The Attorney General has said that for legal reasons this is not possible. But the government can and must resolve this difficulty, so the cash, ordered by the Tripoli government before the rebellion, can be put into the hands of the council. The inflationary effects will be minimal, with only around 300 Libyan dinars per person being put into circulation, and this would give the council an additional four months leeway. When the four months are up, oil might well be flowing from the eastern fields, or, even better, Gaddafi might be gone. If we let the economy of liberated Libya fail, we risk throwing away much goodwill. It will cause untold havoc and risk prolonging a conflict that has already caused great misery, quite apart from damaging Britain’s standing. And of course we also risk creating a fertile environment for extremists. Libya should and could be an example to her neighbours, particularly Egypt. Now that we’ve joined the battle, we must not fail her on this most basic of issues.

A wander through the hotels of Benghazi is instructive. The Tibesti Hotel houses the Foreign Office and its security team and is strategically placed next to one of the three buildings used by the National Transitional Council. The Uzu is the haunt of a depleted journalist pack — most of the hacks have followed the front line to Misrata. And within this hotel-based ecosystem is an alphabet soup of organisations: Unmas, WFP, OCHA, Unicef. The representatives of these acronyms sit discussing matters far beyond my understanding. They talk about capacity-building and leveraging networks, gender-balancing, empowering diversity and tribal dynamics, using shorthand and more acronyms. It is a truly Catch-22 environment. Yet among this crowd are many who are impressive. The WFP have managed to ensure that food is delivered to those who need it both in the east and through Tunisia in the west and, in what might be a unique concession to the Libyan palate, pasta has been added to the menu.

After only a week here, I’m getting Benghazi leg — feeling the need to get out, sharpish. The expats talk of escaping for weekends in Malta, whilst I’m keenly aware that on the doorstep are some of the finest Greek ruins in the Mediterranean: Apollonia, Cyrene and Slonta. But first for me is Ptolemais, where my guide book promises gentle sea breezes, soft sand and hraimeh, a spicy local seafood dish. With any luck, in the future, these will be the reasons we all flock to Libya as tourists.

Comments