The most striking and difficult aspect of this novel is its incredible scale. How can a reviewer best discuss an enterprise containing a vast survey of life in Germany, Britain and the United States and the transformations of these societies from the end of the 19th century to the 1980s?

Two volumes cover the experience of age and youth, the rise of the Nazis in Mecklenburg, the second world war, life and death in a small German town, the evolution of East German communities and the emergence of a Soviet state after the war.

The New York Times appears in more or less every chapter, as the conveyer of the story of the Vietnam war and events in the city of New York itself. There are accounts of Mafia dealings and other street crimes. The protagonists of the novel, Gesine Cresspahl and her daughter Marie, live where Uwe Johnson himself lived between 1966 and 1968: apartment 204, 243 Riverside Drive, New York, NY10025.

Gesine has been living in New York for six years with her clever, restless daughter Marie. Against a background of murder in Vietnam and riots and conflict in Manhattan, Gesine decides to tell Marie the story of Germany and her own life before she arrived in America.

This vast work covers the Holocaust, and in various chapters the deaths of German war criminals and other felons are mixed in with different events:

Herr Paul Zapp, 63 years old, has been arrested in Bebra, a small Hessian town, for the murder of at least 6,400 Jews in the occupied Soviet Union. Until the day before yesterday, an assumed name was all he needed.

The text is dense with detail: Mrs Ferwalter, a neighbour in the building, sits in the park with Gesine, who sees a number tattooed on the inside of her arm and instantly recognises it. The sharp observation of the refugee colonies, the structure of an American office and the way New Yorkers commute all play a part in Gesine’s existence. Her office life adds to the identity of the foreign woman in an American company. Gesine’s addiction to the newspaper reveals the peculiar cult of the New York Times, which she calls ‘Auntie’ (and in 2018 its cult has not changed).

In the meantime, the residents in Jerichow, a small town in Germany, live their parallel lives, as the 1930s and the 1960s merge. Sections in italics express Gesine’s views, but sometimes simply report events. The two worlds of Germany and America overlap when the cemetery gardener’s wife in Jerichow sends a bill to Frau Cresspahl: three graves, 20 marks each.

One of Marie’s homework assignments is ‘Look out the window…’ She records a fire in a neighbouring building:

All the side streets were packed with nervous headlights. My mother said, ‘this is what it’s like in a war.’

‘I did not say that.’

‘You did too.’

‘Did not. . .’

They then argue about what Gesine did say and Marie ends up rewriting the conclusion:

Tomorrow Sister Magdalena will ask her if she is thinking about Vietnam. And it will become a topic at the next parents meeting. ‘You are raising your child improperly, Mrs Cresspahl.’

This wonderful passage between Gesine and Marie grows out of the news about the Holocaust and the fire in Marie’s essay. No transition links the sections, but they fit perfectly. Indeed the text tends to jump from subject to subject without connective prose. It just takes a well-focused eye and ear to catch the link. Gesine and Marie argue about Gesine’s passivity during the anti-Vietnam demonstrations and Marie’s activity. The dialogue is long and rich and reoccurs.

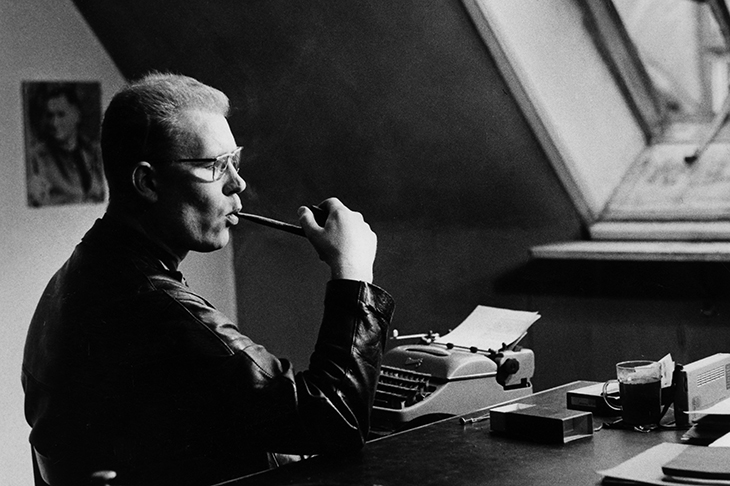

In one episode, Johnson addresses a meeting of the Jewish American Congress on recent developments in Germany and gets rattled. He looks for solace from Gesine, sitting in the back — character and reality interchange:

Who’s telling this story, Gesine? We both are. You know that.

November 29, 1967. Today I’m going to tell you some things on tape ‘for when I am dead’… Listen Marie, if I let myself get involved with someone, their death could hurt me. I don’t want to feel that pain ever again. So that means I can’t let anyone in. This proviso does not apply to a child by the name of Marie Cresspahl. Sorry. You know I don’t talk during the day.

Gesine now tells the story of her life and thoughts, as promised.

After the time in New York we move back to Germany and then to postwar events. Johnson strikes a different tone because Marie grows up and learns to cope with her mother. The occupation of East Germany by the Soviets gives her father Heinrich Cresspahl the chance to become the Russian agent in Jerichow. The relationship between Marie and her mother deepens and gets even more complicated. As indeed the world of the 1950s and 1960 alters all the relationships.

There is no easy way to summarise this immense work. The constant references to the Mafia, the crimes on the streets of New York, the emergence of new characters in the 1970s who enrich the lives of the Cresspahls, the unrest in American politics serve as a background to the lives of the two main characters. Many figures in corporate America engage Gesine for her languages and careful conversation. We follow her resistance to American values, the way the Upper West Side becomes poorer and the residents older and Marie grows up to provide her own story. All I can say is that nothing I have read resembles these narratives, and in their ambition, construction, spirit and atmosphere they constitute an astonishing achievement

The end is melancholy:

As we walked by the sea we ended up in the water. Clattering gravel around our ankles. We held one another’s hands: a child, a man on his way to the place where the dead are, and she, the child that I was.

Comments