In his autobiographical book Surely You’re Joking, Mr Feynman! the late American physicist Richard Feynman described how he amused himself by cracking open the safes at Los Alamos, which stored design papers for the Manhattan Project. He started out picking locks, which he describes like this:

Now, if you push a little wire gadget — maybe a paper clip with a slight bump at the end — and jiggle it back and forth inside the lock, you’ll eventually push that one pin that’s doing the most holding, up to the right height. The lock gives, just a little bit, so the first pin stays up — it’s caught on the edge. Now most of the load is held by another pin, and you repeat the same random process for a few more minutes, until all the pins are pushed up.

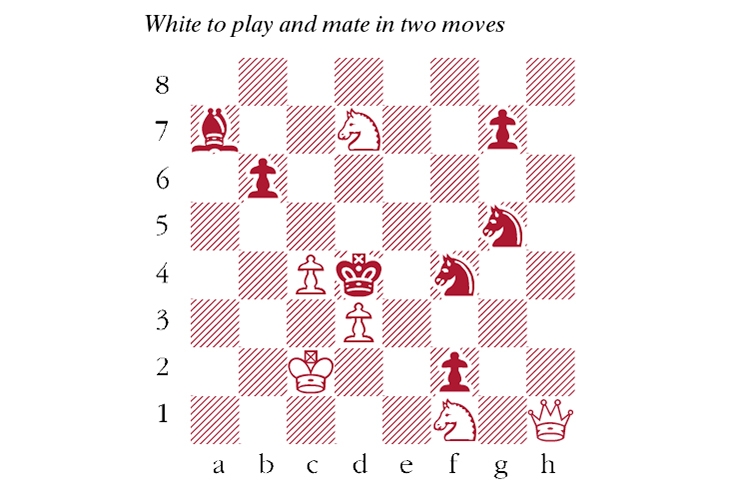

My lock-picking isn’t up to much, unless you count one time when I lost the key to my own suitcase and had to break into it. But I’ve solved a lot of chess problems, and, the resemblance is striking — particularly with composed problems of the ‘White to play and mate in two’ variety. Indeed, in the jargon of chess composition, the first move is known as the ‘key’.

The position shown in this week’s main diagram is the starter problem for the Winton British Chess Solving Championship, an annual competition. White must force mate in two moves, against any defence. (White moves, then Black moves, then White delivers checkmate). For entry details, see the final paragraph.

Hunting for checks or captures feels like applying brute force, which is unlikely to be the intended aesthetic effect of the person who devised the problem. A more fruitful approach is to treat the position as a locking mechanism, and notice which figurative ‘pins’ are already in place. Black’s king is immobilised, and out of Black’s 14 possible knight moves, 12 can already be met with Qe4# or Qd5#. But our key move must also account for the possibility of …Ng2 or …Nf3, blocking the queen’s path. Black has three other legal moves with the bishop and pawns, one of which already has a subtle drawback. One may seek out a key move which carries no direct threat but creates a situation of ‘zugzwang’, in which each Black move can be met with mate. Of course, one must maintain the equipoise which already exists among the other pieces. Like Feynman’s lock-picking, it can take considerable trial and error to find a move which aligns everything correctly.

Entries are by email to winton@theproblemist.org no later than 31 July. Only the first move is required. Successful entrants qualify for a postal round, so do include a name and address. Mark your entry ‘The Spectator’! Those who were under 18 on 31 August 2020 must give their date of birth. For more details about the competition, including how to enter by post, visit https://bit.ly/38Q46E2. For more information on the rich world of problem-solving, visit ‘theproblemist.org’. The website has an excellent section titled ‘For Beginners’, in which the ‘Two-Move Secrets’ section may provide inspiration.

Comments