Everyone loves a private view, and I am no exception. I don’t know how many hours I must have spent trudging around central London’s art galleries in search of warm white wine – my social life doesn’t extend much beyond the confines of that circuit to be honest. Lately, however, I’ve been to some dreadful things; shows that seem to exist purely in order to enable their ritzy opening galas. I suppose I have only myself to blame for turning up to an evening at London’s stupidest gallery last week, but it was truly horrible: a party thrown for a scenester artist who turned DJ for the night, spinning butchered mash-ups of 1980s club hits to a scrum of pouting influencers. As for the art: suffice to say I’m not giving anyone the dignity of a namecheck. (The gallery was Saatchi Yates.)

It was all making me feel a bit cynical. But then, at the tailend of the week, I saw two exhibitions of such remarkable quality that I remembered why I got into the game in the first place. The first came courtesy of the indefatigably brilliant Suzanne Treister, an artist of such dazzling originality that she puts most contemporaries to shame. And Prophetic Dreams, her career retrospective at Modern Art Oxford, is unquestionably one of the shows of the year.

Treister (b.1958) has spent much of her career being labelled as a conspiracy-obsessed paranoiac: decades ago, she was warning that personal technology offered a gateway to pernicious new forms of surveillance. Nobody listened, but the leaks and revelations that spilled out after 2014 proved her right.

But she’s more than a mere Cassandra, and the show does a fine job of demonstrating the breadth of her uncanny, heavily researched practice. Things kick off with a series of Balthus-inflected surrealist paintings that she made in the early 1980s, marrying Jewish mystical signifiers to weirdo, cod-symbolist arrangements that mimic the aesthetic of Soviet socialist realism: they’re eerie things that seem to prefigure the concerns and mood of her various projects to follow.

Treister fields custom-designed video games, including delicate miniatures painted on to floppy discs; mocked-up CD cases; even a music video, purportedly the work of a time-travelling pop star called Rosalind Brodsky – the song, rather marvellously, is entitled ‘Satellite Of Lvov’. Then she switches tack again, presenting a series of informational flow charts encompassing the totality of modern society, from monetarism to the American government’s weird ventures into the realm of mind-expanding drugs. You could spend a month in here following the connections Treister teases out in her work: I had an hour and loved every second of it.

You’ll never look at a discarded KFC box in the same way again

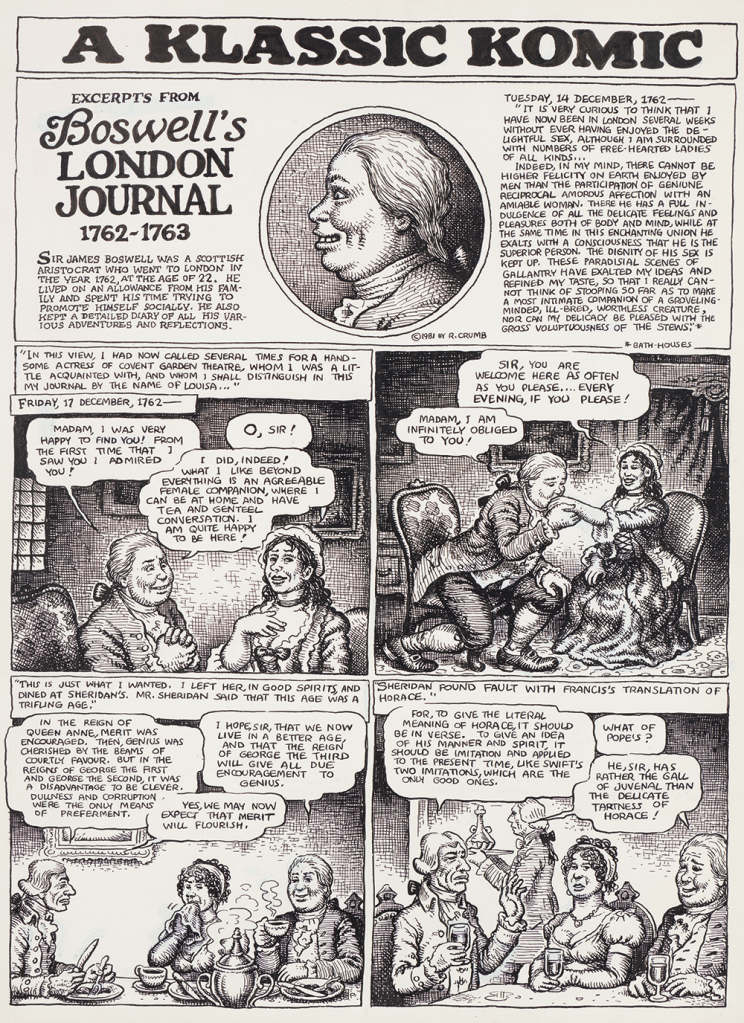

The second stunner is on at Cassius & Co, a delightful gallery in Knightsbridge with a short but superb track record of exhibitions. The cause this time is Robert Crumb, the great American cartoonist described by Robert Hughes as the Bruegel of our times. I don’t know about that, but he’s certainly our Hogarth. The latter artist looms large in this show, which is devoted to a 1981 comic he made based on James Boswell’s marvellously picaresque London Journal (1762-63, see below). Crumb follows a boozy year in the life of the young Scottish aristo as he smooths his way through various Georgian salons, gets rejected by an actress, recruits a whore, swears he’ll never do that again and – obviously – ends up making a habit of it.

Flitting between earnest Enlightenment discussion and gripes about the women he encounters – ‘her avarice was large as her a–––!’, he complains of one contractee – Boswell is a natural subject for Crumb, a leering 18th-century cousin to his earlier Fritz the Cat. The artist lifts compositional structure from various plates of A Rake’s Progress, rendering the panels in a heavy cross-hatching that consciously and reverently nods to Hogarth’s hand.

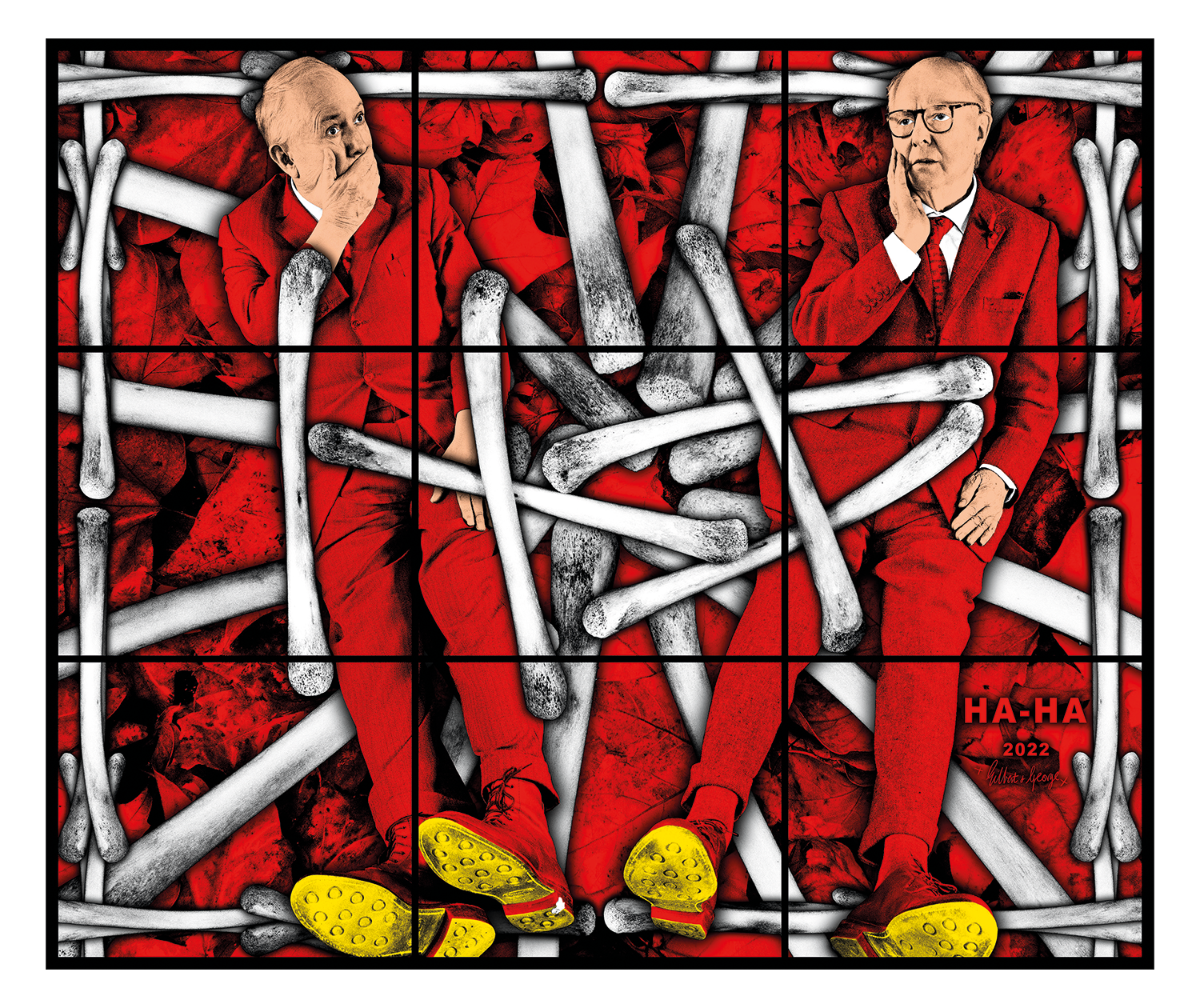

Now in their eighties, the artist duo Gilbert and George are being celebrated with a late-career retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, a typically entertaining show which contains some of the most striking memento mori in all modern art. They’re still making the same, aggressively-coloured multi-panel works for which they’re best known, but lately a new motif has crept in: chicken bones, scavenged from the pavements of east London and repurposed as intimations of the inevitable. It’s a simple, effective and very on-brand shorthand – and, I thought, a deeply moving one. Your wider impression of the exhibition will depend on your tolerance for Gilbert and George themselves; whatever you think, you’ll never look at a discarded KFC box in the same way again.

Comments