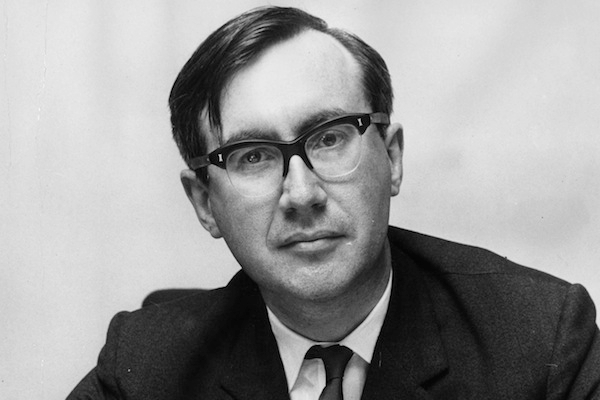

William Rees-Mogg, who has died, the Oxford-educated member of an old Somerset family, was widely seen as the archetypal ‘gentleman journalist’, but he aspired to be rather grander than that. Even before he became editor of the Times in 1967 he had upstaged his landowning forebears by buying himself an enormous 18th-century country house, Ston Easton Park near Bath, complete with fancy plasterwork, which he set about restoring and embellishing. He even asked the Times’s then Rome correspondent, the late Peter Nichols, to see about getting a replica made of Bernini’s boat-shaped fountain in the Piazza di Spagna — the famous Fontana della Barcaccia — for placing on the gravel sweep in front of the house. Nothing came of the idea, and perhaps it was never completely serious; but it was what Peter told me, and, given the character of the man, it seemed quite plausible.

Rees-Mogg felt destined to become a pillar of the Establishment; and when he was thwarted in his political ambitions, he achieved his goal through journalism. His grave, thoughtful appearance assisted his rise: he just looked the part of an Establishment grandee. And he was a reassuring presence among the rich and powerful, someone who could articulate their opinions for them and make them feel cleverer than they were. He was himself, of course, clever and an excellent journalist, and he was far from being the pompous ass he was sometimes caricatured as. He was kind and generous, and, like most journalists, he enjoyed gossip and jokes and trouble.

It is to Rees-Mogg’s troublemaking side that I owe the fact that ever since 1980 my birthday has been published in the Times each year. In 1979, the late Auberon Waugh, in one of his weekly columns in The Spectator (of which I was then editor), had described what happened when he tried to get his own birthday mentioned in the Times. He had written to the paper’s Court and Social page editor, a young woman he had never met, to say that he was shortly to be 40 years old and would like to invite her to lunch to discuss this important event. She declined the invitation in a letter saying that she was too busy, but wishing him a happy birthday. Nevertheless, the anniversary passed unmentioned in the newspaper. This prompted Waugh to refer to her in The Spectator as ‘the cow’.

Rees-Mogg rang me at home that evening to ask when my birthday was. He said he would have been happy to put Waugh’s birthday in the Times; but since he had called his Court and Social page editor a ‘cow’, he now intended to get his revenge. He would do this, he said, by putting my birthday in the paper instead — something he guessed would annoy Waugh considerably. So, thanks to Rees-Mogg, my birthday has for the past 33 years been reported annually in the Times and, consequently, in the other ‘quality’ newspapers as well — the one exception being the Guardian, which dropped me from its list a few years ago, possibly on the grounds that, as one of its columnists, I could not possibly deserve such an honour. Being dropped is, of course, much more hurtful than not being included in the first place because (as Peter Fleming once wrote in The Spectator after his birthday had been dropped by the Times) it means that somebody has consciously taken the decision that you are no longer worthy of inclusion.

Rees-Mogg was once offered the editorship of The Spectator, but turned it down, only to become editor of the Times soon afterwards. But he did the magazine a great favour in 1978, the year in which we celebrated our 150th anniversary. The magazine was then at a very low ebb, selling perhaps around 13,000 or 14,000 copies a week, and widely considered to be in danger of extinction. Indeed, at around that time, Anthony Howard, former editor of the New Statesman, was to write an article in the Times sounding the death knell of the political weeklies. But suddenly, on the editorial page of the Times on 22 September 1978, there appeared a leading article written by the editor himself in which The Spectator was hailed as the standard-bearer of ‘the most interesting intellectual movement of our times’, the movement away from collectivism. The Spectator, Rees-Mogg said to our surprise and bemusement, was now a powerhouse of intellectual originality and vitality. Since then we have never really looked back.

Comments