These are going to be dark days of introspection for Conservatives. And, as they try to make sense of the 2024 election, some will look to the party’s past to put it into historical perspective. There is, however, no precedent for how awful the result was for the party in terms of vote share and seats won: it really was that bad.

Yet, as a comfort amongst the wreckage, but also an inspiration for future effort, some party members will likely alight upon earlier examples of how the Conservatives recovered from cataclysmic defeat. Of those modern instances – 1906, 1945 and 1997 – 1945 is by far the most appealing. After being thumped by the Liberals in 1906, the Tories needed the first world war to get back into government as part of a coalition; after Tony Blair took them to the cleaners in 1997, an international financial crash was required to help them win office again and then only in another coalition. But after 1945, the Conservatives bounced back almost immediately, through their own efforts and to great effect.

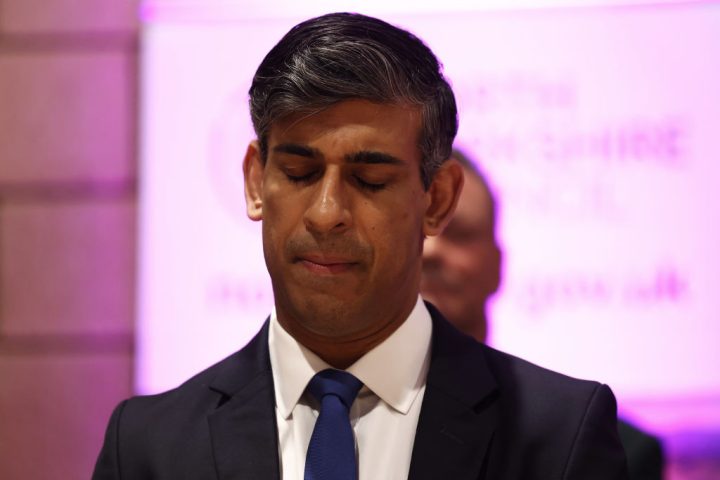

Moments such as this are especially disconcerting for Conservatives

In July 1945, Britons unexpectedly gave Winston Churchill a bloody nose, despite his warning that Clement Attlee would need ‘some form of Gestapo’ to implement Labour’s manifesto. Instead, voters rewarded Labour with its first ever Commons majority – and one of 145 seats at that. Commentators speculated that Attlee’s party would be in office for a generation. Such was the scale of defeat, Harold MacMillan called for Conservatives to change their party name and merge with the Liberals.

Yet by the February 1950 election, Conservatives had reduced Attlee’s majority to just five. When the prime minister sought to improve this position in October 1951, it was the Conservatives who triumphed, winning a majority of 17. The party would increase that majority in two subsequent elections and remain in office until 1964.

But if they go misty eyed at what happened seven decades ago, Conservatives should remember that the past is another country: they do politics differently there. Most obviously the party’s position is more complicated today than it was then. After 1945, Conservatives only had to move in one direction to improve their electoral position: to the left. And the leadership did that with alacrity, accepting most of Labour’s 1945 programme while insisting they were doing no such thing.

In 2024, however, the party has seen its vote fracture in various directions. Not only must Conservatives now appeal to those who abandoned them for Labour and the Liberal Democrats – but also for Reform. Nigel Farage’s intervention has massively complicated its path to recovery. Now, the party must determine which direction it should travel in during this parliament: left or right or both at the same time?

The Conservatives’ move left after 1945 was moreover imposed from the top on a sceptical but disempowered and deferential membership. Led by Rab Butler, who chaired the Conservative Research Department, policy was revised to become, in essence, a watered-down version of Labour’s statist reforms.

Despite ideological misgivings, the party grudgingly accepted this as the price of returning to office. Ideas mattered but not as much as exercising power. So, when Churchill was given a draft speech by a callow Research Department official embracing most of Labour’s nationalisation programme he told him: ‘I don’t believe a word of it’. Even so, the leader obediently read it out to conference delegates’ loyal applause.

In contrast, today leading Conservatives – most obviously Suella Braverman – refer to their party possessing a ‘soul’, a precious entity that has somehow been lost and needs to be rediscovered. To them, ideas – pure Conservative ideas, notably those of the small state and low taxation, are now themselves central to winning back power. And many party members, who ultimately determine the outcome of any leadership contest thanks to William Hague’s 1998 reforms – agree. The scope for a pragmatic leadership emulating Butler’s middle-of-the-road course back to power looks decidedly slim.

After 1945, Conservatives enthusiastically exploited Attlee’s problems as Labour tried to turn a wartime economy into an export-focused peacetime operation amidst a world in turmoil. Rationing, shortages and queues for essential goods became worse while nationalisation did not prove the panacea some hoped. The widespread frustration that things were not getting better allowed the party to appeal especially to middle-class voters who had supported Labour for the first time in 1945.

Conservatives will hope to do the same in this parliament as Prime Minister Starmer tries to encourage the kind of economic growth that has eluded most recent governments to finance promised improvements in the public services. But it is unlikely that critiquing Labour will be enough on its own if the Conservatives are to fully regain the initiative.

In contrast to Labour – which has suffered defeat so consistently and dramatically that it had almost become an old friend – moments such as this are especially disconcerting for Conservatives. So far, they have always recovered. But just because they have bounced back in the past does not mean they always will. Certainly, for the foreseeable future, the route back suggested by 1945 – adapt many of your opponent’s policies as the price worth paying for power – no longer seems open to a party forced to look left and right at the same time while its members argue over the precise character of Conservatism’s ideological ‘soul’. They could be in opposition for a very long time indeed.

Comments