Back in 2007, I went to war-ravaged Guinea-Bissau in west Africa to report on its rise as the continent’s first narco-state. Latino cartels were using it as a staging post for shipping cocaine to Europe, bribing its rulers to turn a blind eye. So much product was being landed that local fishermen would catch stray bales of coke in their nets – a modern twist on Compton Mackenzie’s novel Whisky Galore.

Guinea-Bissau’s new drug lords would go on to inspire a novel of their own. Back home on the Telegraph foreign desk in London a few months later, I got a call from no less a figure than Frederick Forsyth. His next novel, he told me, was going to be about the cocaine trade, set in coup-ridden west Africa: Narcos meets The Dogs of War. Could I fax him my article (he was a famous technophobe) and pass on a few contacts? Oh, and any recommendations for a hotel? Despite already pushing 70, he was still the roving correspondent that he started out as, keen to see things for himself.

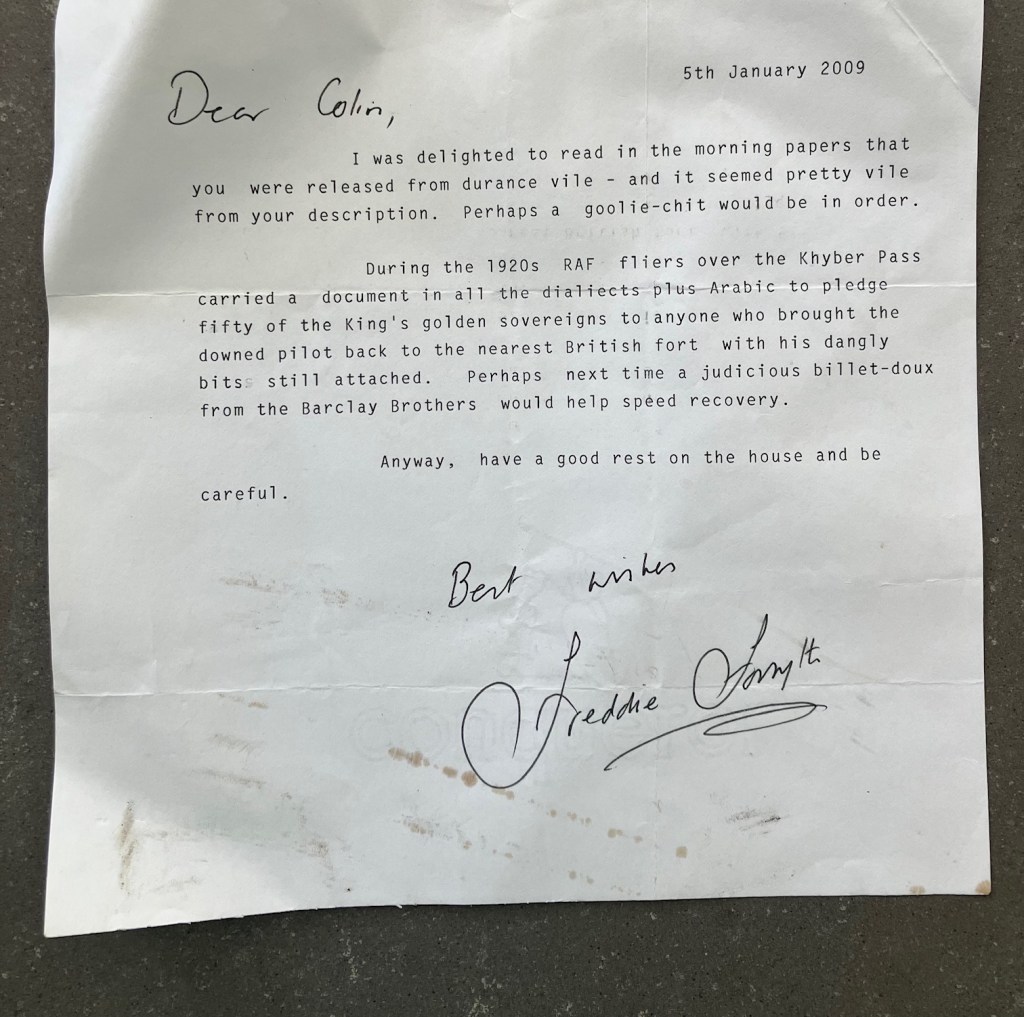

I didn’t hear from him for a while after that, during which an assignment to another African country got me into serious trouble. Sent to Somalia the following year to report on pirates, I was kidnapped and held hostage for six weeks in a cave. It was like a grimmer chapter from one of Forsyth’s own books, although it did earn me a personal note of consolation from the author himself. When I finally returned to the foreign desk after being released, a signed, hand-typed letter from him was waiting for me.

Dear Colin, I was delighted to read in the morning papers that you were released from durance vile – and it seemed pretty vile from your description,’ he wrote (referencing, I think, my account of wearing the same clothes for 40 days). ‘Perhaps a goolie chit would have been in order.

A ‘goolie chit’, he explained, was the nickname for the promissory note that RAF pilots carried when flying over the tribal belt of the Khyber Pass in the 1920s. Written in local dialects, it promised 50 golden sovereigns ‘to anyone who brought the downed pilot back to the nearest British fort with his dangly bits still attached.’ Had I been issued with a goolie chit by the Telegraph foreign desk, Forsyth added, the pirates might not have detained me so long.

Here, I suspect, the master thriller writer was wrong. An up-front cash offer would likely have just tempted my captors to demand ten times more. But to this day, the letter has pride of place in my box of foreign correspondent memorabilia, alongside a golden dummy gifted to me by the Gaddafis for my newborn daughter, and an airline sick bag autographed by Midge Ure (long story).

The letter was also proof, I think, that despite becoming one of the world’s most famous novelists, Forsyth remained an old-school hack at heart. He didn’t put on airs and graces, and still knew the value of the personal touch – to the point where he was happy to ring up nonentities like me rather than have some researcher do it. It was his journalistic shoe leather, though, that also made his novels so realistic, the fiction merely a tweaked version of the facts he’d already researched.

As he records in his bestselling biography, The Outsider, Forsyth started life as a reporter on the Eastern Daily Press in Norfolk, before working for Reuters in Paris, East Germany and then the BBC in Nigeria during the Biafran War. Every foreign correspondent thinks they could get a book out of their reporting days: Forsyth got at least three, including his most famous ones.

The Day of the Jackal was based on his stint in Paris, where his job was to tail General de Gaulle around lest he were assassinated. The Odessa File was based on his time as Reuters’ man in East Berlin, where he heard of secret networks of ex-Nazis. And The Dogs of War drew on his encounters with British and French mercenaries in the Biafran War. He also spent two years in Nigeria as a freelancer, no easy task in a war zone. As a former freelancer myself, I wonder whether that informed his empathy for the nameless hitman in The Jackal – another loner living by his wits.

It was the minor detail in Forsyth’s books, though, as much as the big themes, that sold them by the million. To find out how the Jackal might acquire a fake identity, Forsyth interviewed a professional forger. By hanging around with de Gaulle’s bodyguards, he learned that the French secret service were already monitoring France’s top hitmen – hence the Jackal being English, not French. By consulting a gunsmith, Forsyth came up with a feasible blueprint for the Jackal’s assassin’s collapsible, concealable rifle.

Yet when Forsyth went on his research trip to Guinea-Bissau, he walked into what seemed like an overheated version of one of his own scripts. During his visit, a violent military coup attempt unfolded – caused, allegedly, by feuding over cocaine profits within the country’s elite. Forsyth later recounted how he was staying in his hotel (hopefully the one I recommended) when he heard the sound of fighting. ‘I was reading and heard a hell of a bang down the street and I knew it was not thunder but an explosion,’ he said. ‘I didn’t come for a coup d’état or regime change, but that’s what I ran into’.

To this day, the letter has pride of place in my box of foreign correspondent memorabilia, alongside a golden dummy gifted to me by the Gaddafis for my newborn daughter

The following day, it emerged that a bomb had killed General Batista Tagme Na Wai, the armed forces chief of staff. In revenge, his men had attacked the house of Guinea-Bissau’s leader, President Joao Bernardo Vieira, hacking him to pieces. While it lacked the finesse of the Jackal’s killing methods, it was the first time that cocaine cartels had been linked to the assassination of a head of state. As Forsyth himself put it: ‘In Guinea-Bissau, there is no need to exaggerate. This place is for real.’

When Forsyth’s Guinea-Bissau thriller, The Cobra, was published, he sent me a trade proof copy – a roughly produced first draft usually only sent out to reviewers. As he pointed out in his letter, ‘it may not have the glitter of a published hardcover, but it is one of only 20 issued’. He was hinting, I think, that it might one day be a collector’s item – and that if I wanted to, I could always flog it. Once again, I sensed the hard-bitten freelancer talking.

That was not to be the only time that Forsyth’s world and mine blurred into one. In his 2013 book, The Kill List, there’s a hostage negotiator called Gareth Evans, employed by London insurance firms to secure the release of sailors hijacked by Somali pirates. Like a very high-stakes poker player, Evans knows every bargaining trick in the world. He also bore a resemblance to ‘Leslie Edwards’, the negotiator who’d secured my release back in 2008. Sure enough, when I asked Edwards earlier this week, he confirmed that Forsyth had got in touch.

‘A very decent chap – he invited me to lunch,’ Edwards told me. ‘He completely ignored my advice, as it happens, with some daft plot line about a pirate chief who was gay, and who wanted to bugger the hijacked ship owner’s son, who was on board. The book was a commercial and critical flop, if I remember rightly. But it was a fine lunch.’

OK, so perhaps even the finest thriller writers can over-egg the plot sometimes. But mostly, Forsyth got his facts spot on. The year after my kidnapping, I returned to Somalia’s pirate coast – this time on a Royal Navy frigate doing an anti-piracy patrol. On board was a helicopter pilot, who had the unenviable task of skimming the coastline taking photographs of pirate hideouts. In the event of his helicopter crashing, he was equipped with a wad of $20,000, along with a note in Somali promising more to anyone who took him to safety. Or – as I already knew to call it – a ‘goolie chit’.

Comments