The French are falling back in love with nuclear energy, and so is their president. In 2019, only 34 per cent of people polled expressed a positive view of France’s nuclear programme, a figure that had increased to 51 per cent two years later. The most recent survey revealed it to be 60 per cent.

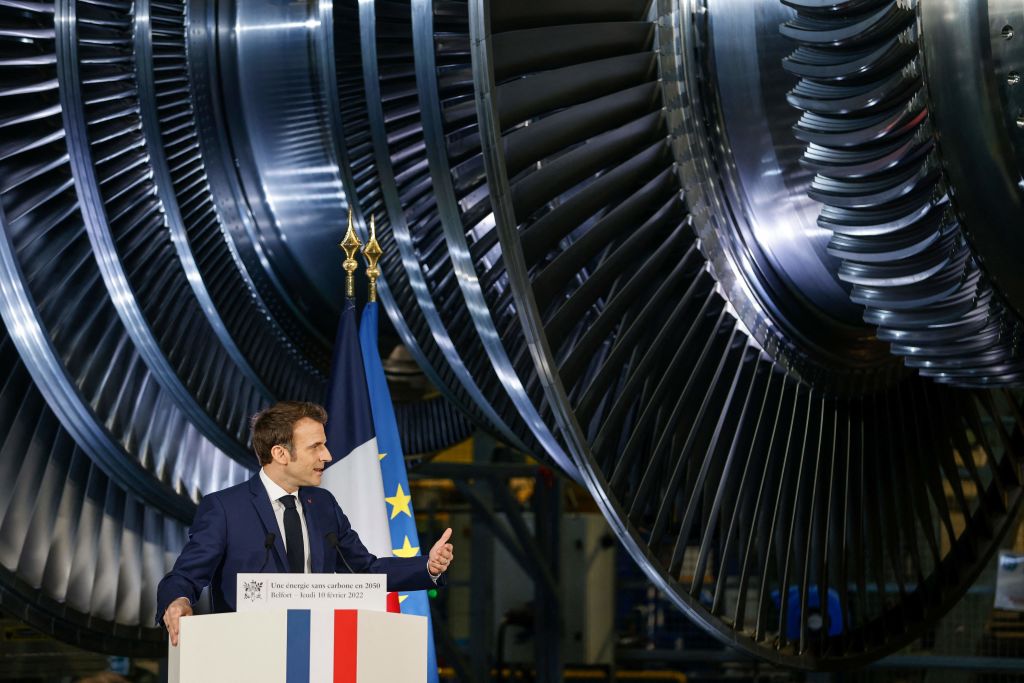

If Emmanuel Macron had been polled he would have given nuclear energy the thumbs up, a reversal of his position when he was first elected president in 2017. He came to office promising to reduce the share of nuclear power in the energy mix to 50 per cent by 2025.

If France has understood the urgency of relaunching its nuclear programme, Britain appears slower on the uptake

The next year he delighted Germany by announcing that France would shut down 14 nuclear reactors by 2035, six of which would be closed by 2030.

But as the reality of reducing France’s dependency on nuclear energy began to bite, so Macron began to have second thoughts. First, he pushed back his 50 per cent reduction target from 2025 to 2035, and then last February he announced in a speech the ‘renaissance of the French nuclear industry’.

Six new-generation reactors would be built, declared the president, with the possibility of a further eight. ‘Some nations made radical choices to turn their backs on nuclear,’ said Macron. ‘France did not make this choice. But we did not invest because we had doubts.’

Vladimir Putin dispersed those doubts. Two weeks after Macron’s volte-face, Russia invaded Ukraine, plunging Europe into an energy crisis and the French president into a political one. As energy bills have risen, so has the anger of the people, particularly small traders unable to pay bills that they quadrupled and more in the space of a year.

On Tuesday evening the French Senate began examining the bill for the relaunch of the country’s nuclear programme, which currently produces 70 per cent of its electricity. Only the Greens are opposed to the construction of new nuclear reactors; Communist and Socialist senators approve, while also supporting the development of renewable energies, and the only gripe of the centre-right Republican senators (by far the biggest group) is that the nuclear industry should never have been questioned in the first place.

The future of the nuclear industry was a major theme of the 2012 presidential election; the incumbent, the Republicans’ Nicolas Sarkozy, argued in favour of its maintenance, while his challenger, the Socialist Francois Hollande – spurred on by German chancellor Angela Merkel – wanted to rid France of its reliance on nuclear energy.

Hollande won the election and the French nuclear industry went into decline, to the point where last summer 32 of the country’s 56 reactors were not operational.

Last month the former CEO of EDF, the state energy giant, Jean-Bernard Lévy, appeared before a parliamentary committee that was examining ‘the loss of energy sovereignty of France’. Lévy didn’t pull his punches, accusing successive governments of neglecting the nuclear industry. ‘It is not possible to be competent and efficient when one builds a reactor every 15 years’, he said.

France is now playing catch-up and the Nuclear Safety Authority (ASN) wants the government to launch a ‘Marshall Plan’ for nuclear power. The indifference to the industry this century has led to a shortage of skilled technicians and engineers – one reason why the maintenance of the reactors takes so long – and the ASN has submitted a plan to recruit 10,000 people per year until 2030. EDF is scheduled to begin preparatory work for the first new reactor at Penly (close to Dieppe) next year. The bill being examined by the Senate will ensure that this work goes to schedule by shortening administrative and environmental procedures.

The relaunch won’t come cheap. According to Le Figaro, the first six reactors will cost €51.7 billion, a hefty sum at a time when the state’s – and EDF’s finances – ‘are stretched to the limit’. EDF has incurred €65 billion of debt, and is expected to post a loss for 2022 that will rank among one of the heaviest ever by a French company.

Once the Senate have approved the bill it will go to the lower house for ratification, but Macron knows it will pass, having the support of the Republicans and Marine Le Pen’s National Rally MPs. Even the Communists are behind it, their leader, Fabien Roussel, explaining that: ‘I took this pragmatic position after many discussions with researchers and experts… We need to increase the share of the energy mix, but we must be careful: these energies must be truly renewable.’

Only Greens and some left-wing MPs are expected to oppose the bill, maintaining that the future should be 100 per cent renewable energy.

If France has understood the urgency of relaunching its nuclear programme, Britain appears slower on the uptake. A report in Monday’s Daily Telegraph accused the government of ‘feet-dragging’ over the question of increasing Britain’s reliance on nuclear energy.

A strategy report published in 2022 set the target of nuclear plants supplying a quarter of Britain’s power by 2050 (it is currently 14 per cent) but this objective will be met only if the government acts with the same alacrity being shown by the French. But according to the Telegraph, since Boris Johnson left No. 10 enthusiasm for expanding Britain’s nuclear plants has waned with the Treasury ‘queasy about the generous public subsidies required for new plants.’

The most recent survey revealed that nuclear energy is becoming more popular with the British public, with 48 per cent supportive last September, a rise of 10 per cent since the start of the war in Ukraine.

Last Friday former energy minister Chris Skidmore published a Net Zero review that stated nuclear power is a ‘no-regrets option’ and he advised the government to move its capacity targets from 2050 to 2035. Tom Greatrex, chief executive of the Nuclear Industry Association, was more blunt: ‘Nuclear is an integral part of a future secure, clean power mix,’ he said. ‘Rather than further procrastination, the government should respond with pace and urgency.’

As they are doing in France.

Comments