In Stratford-upon-Avon, the wolves are running. And if you’re old enough to feel a little thrill of wintery excitement at those words, you’ll have questions of your own about the Royal Shakespeare Company’s The Box of Delights. Questions about talking rats and flying cars, and whether time and tide and buttered eggs still wait for no man. John Masefield’s novel thrived on radio adaptations for decades after its publication in 1935 but the beloved BBC TV version was in 1984, and four decades is a horribly long time. Piers Torday’s new dramatisation faces the double challenge of entertaining a new generation of youngsters while also pleasing the nostalgia-addled oldies who are, after all, splashing the cash.

When did the Royal Shakespeare Theatre last see such a teeming, joyous abundance of stagecraft?

I can’t speak for the kids, although the ones at this Saturday matinee seemed rapt. The first scene is ominous – a modern-day Kay Harker (Callum Balmforth) dressed in a tracksuit – but don’t panic. A familiar harp motif (from Hely-Hutchinson’s Carol Symphony, as used in all those classic adaptations) is an early signal that we’re among friends and the director, Justin Audibert, quickly goes all-in on a snow-covered 1930s world of steam trains, possets and schoolboys in caps.

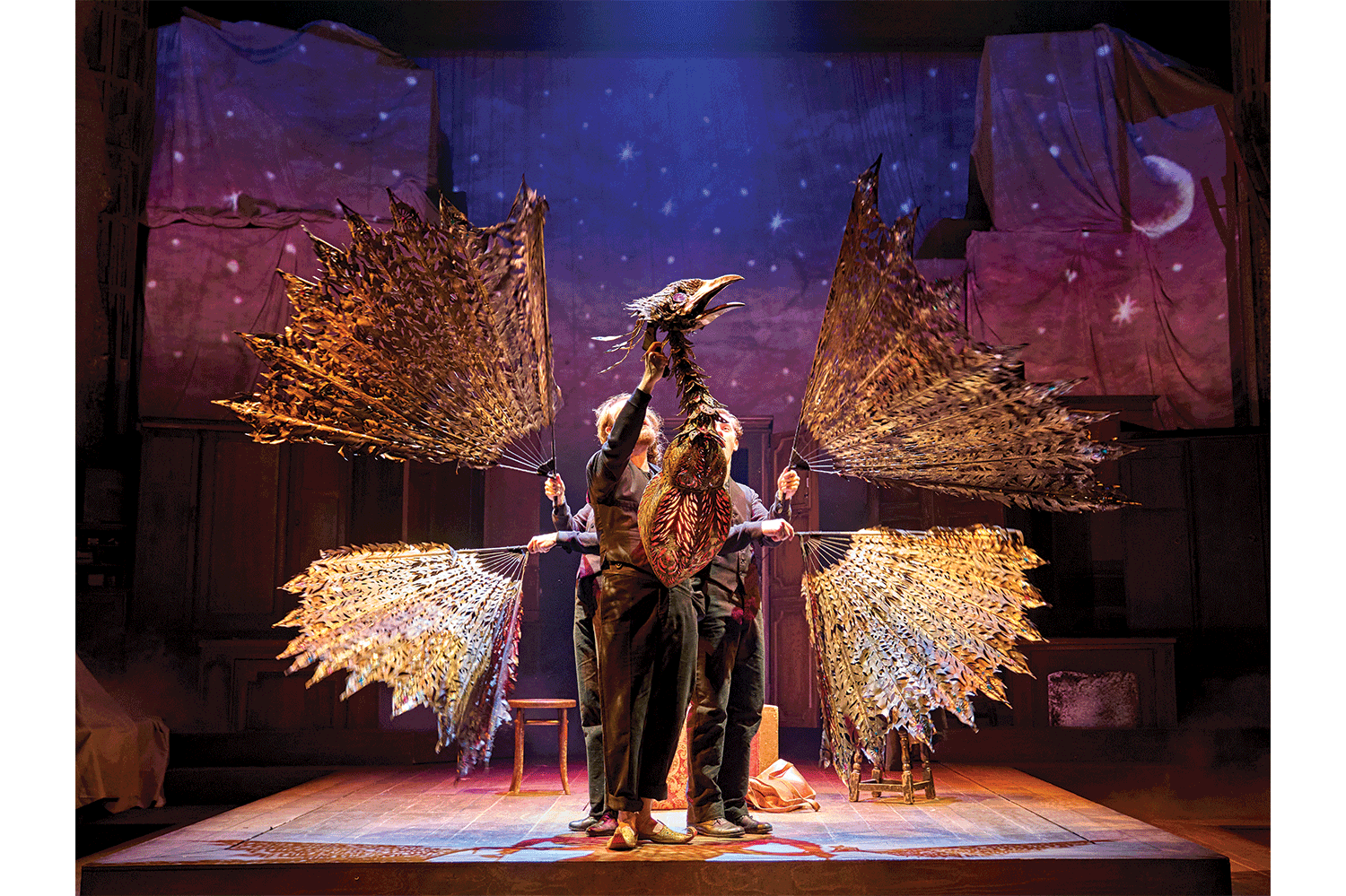

And all-in on the magic too: in Tom Piper’s designs a mountain of wooden wardrobes (a nice shout-out to another children’s classic) becomes a country house, Herne the Hunter’s forest and a tangle of half-timbered streets. Meanwhile Cole Hawlings (Stephen Boxer) vanishes into a painting, and video projections and rippling silk create an underwater world. There’s shadow puppetry and actual puppetry, including a beer-drinking, carol-singing dog. When did the RST – where scenery is usually treated as a micro-aggression – last see such a teeming, joyous abundance of stagecraft? Not since the Simon Russell Beale Tempest in 2016, I’d guess.

The nice thing is that Torday and Audibert resist any temptation to send Masefield up, or turn it into a panto. True, a few gags are on the broader side and the younger actors can’t do RP without parody (they soon default back to something more natural). Kay’s friend Peter (Jack Humphrey) seems to have turned into Walter the Softy.

But on the whole, The Box of Delights is played for what it is, by a cast and company who clearly love the material. Balmforth is a likeable, sweet-natured Kay, and if Mae Munuo’s irrepressible tomboy Maria gets all the best lines, well, that’s pretty much exactly what happens in the book. Boxer plays Cole Hawlings as a Victorian showman, wearing his air of mystery with gentle authority and making a powerful foil to Nia Gwynne’s vampish, predatory Pouncer and Richard Lynch’s Abner Brown: properly psychopathic in his silk dressing gown and delivering vintage Masefield-isms in a pinched, eldritch rasp. ‘Scrobble who you have to!’ he screeches, and you’d better believe people get scrobbled.

It’s not a show for very small children (and the first half is on the long side). But Masefield’s spookiness and lack of sentimentality remain central to its appeal, which is why the one major new element – a Harry Potter-ish back-story about Kay’s absent parents – rang false. To this oldster, anyway: possibly the pre-teens expect redemption arcs these days. It’s their story now, and this is a smashing way to pass it on.

Shortly after 7 October, it was reported that Tracy-Ann Oberman’s touring production of The Merchant of Venice 1936 had been obliged to take on additional security, and this reworking of Shakespeare could hardly be more timely. Cold comfort for Oberman, for whom the idea of a Merchant set in the East End Jewish community before the Battle of Cable Street is apparently a long-cherished passion project. In order to grapple directly with the problem of Shylock, Oberman and director and co-adaptor Brigid Larmour strip away huge tracts of the original play. Essentially, Shakespeare’s B plot becomes the centre of a fast, fierce and intensely troubling interrogation of antisemitism.

Oberman is commanding as Shylock: occasionally playing to stereotype, at other times shockingly raw in her brutalised humanity (she trembles with revulsion as she steps forward, knife in hand, to claim Antonio’s flesh). In keeping with the focus, Antonio (Raymond Coulthard), Bassanio (Gavin Fowler) and the rest are cruel, constipated toffs, while Hannah Morrish’s Mitford-alike Portia isn’t so much icy as entirely emotionally frigid. Jessica (Grainne Dromgoole) recoils as if struck when addressed as ‘Jewess’ and the pronoun problems created by cross-gender casting simply don’t arise because – as you gradually realise – Shylock is more likely to be called (they spat the word out) ‘the Jew’. No graceful evasions, nothing to let us off the hook: the Act Five idyll is savagely cut. This isn’t an easy watch, and some would doubtless prefer to think that it isn’t really Shakespeare. But right here, right now, it shakes you to the core.

Comments