The title Her Deepness is partly satirical, partly reverential. The woman herself, Sylvia Earle, is an American oceanographer and a global campaigner for maritime preservation. She dropped into London last week to collect a medal from the Royal Geographical Society and her visit coincided with a month-long promotion at Selfridges in Oxford Street. The shop decked itself out in deep-sea livery to alert us all to the perils of overfishing. Frogmen patrolled the escalators. Kids cavorted on whale-rides. Cardboard silhouettes of leaping marlin dangled from the ceilings. The shop windows were blazoned with slogans intended to foster alarm. ‘For every shrimp caught, ten other lives are lost.’ ‘In the blink of an eye sea-life could be extinct.’ I’m due to meet Her Deepness in the Ultralounge, which sounds like a private club where film stars inject heroin but turns out to be a cosy little lecture-room in the basement, halfway between Kitchenware and Luggage.

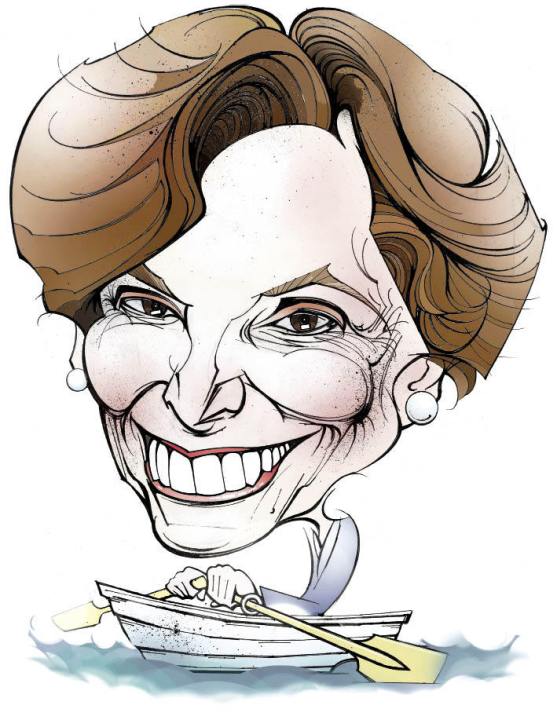

She’s in her mid-seventies, beautifully turned out, her chestnut hair bobbed and combed, her eyes shrewd and faintly steely. Her Deepness exudes gravity and purpose. She’s dressed in a trousersuit of costly but unremarkable green. It’s the armour of the successful pressure-groupie, the ethical arm-twister. We start with a bit of small-talk which, in oceanography, means plankton. One of the bolder assertions outside the shop had caught my eye. ‘Fifty per cent of the air we breathe comes from plankton.’

‘It’s more than 50 per cent,’ says Her Deepness immediately.

‘But breathable air from plankton?’ I ask. ‘Are there some connecting stages in that statement that I’m missing?’

Her Deepness pauses. She has come face to face with His Shallowness, an inquisitor so ill-informed that he doesn’t know a petal from a dorsal or an octopus from a crab-apple. ‘A process we call “photosynthesis”,’ she says, giving each syllable a slow and even stress, ‘enables organisms to take carbon dioxide and generate oxygen and produce food. It’s what grass does. It’s what trees do.’

‘Oh God,’ I say. ‘I’ve got plankton completely wrong. Are they animals or plants?’

‘Both,’ she tells me.

‘Phew. I didn’t realise they could be plants as well.’

She explains the interdependent cycles that sustain our oceans and which reckless fishing threatens to destroy. ‘When a whale eats krill in Antarctica it returns nutrients to the sea which drive the plankton that feed the krill that feed the whales. It’s been doing this for hundreds of millions of years. We’ve come along, mostly in the latter part of the 20th century, and we’ve become expert at finding, extracting, shipping and marketing ocean wildlife on a global scale.’ She suggests that we move towards ‘sustainable closed systems’, aquariums and ponds, ‘where you can raise plant-eating fish, like carp, which are low on the food-chain. And they grow fast.’

The campaign faces a major difficulty, the ‘cold-fish’ problem. We humans struggle to care about species that aren’t furry or cuddly, that don’t pout for the cameras or wear wounded expressions or bleat pathetically when being hunted down. The solution is to establish an explicit connection between fish and their softer, more snuggle-friendly cousins on land. ‘Think of everything in the fish-market as bush meat,’ she says. ‘These are the eagles, the owls, the lions, the tigers, the snow-leopards, the rhinoceroses of the ocean.’

Though reluctant to condemn people’s eating habits, she clearly reviles the impulse that has put shark on restaurant menus. ‘There’s nothing in our biology that suggests that eating sharks is good for us. Maybe we think it’s a macho meal. If I eat a shark I’ll be like a shark! People like to do exotic things.’ She tells me of a deep-sea delicacy, orange roughie (Hoplostethus atlanticus), which is prized for its exceptional lifespan. ‘It takes 30 years to mature. It may be 200 years old when it’s caught. So it may have started its life at the beginning of the industrial revolution. And there it is on my plate to be demolished in 20 minutes. That’s too costly. It’s left a hole in the ocean we can’t fill.’

Does she eat fish at all? ‘I lost the taste because I asked the question: where did this lobster, this clam come from? When I hear the answer, I think, no thank you.’ This is the key to her campaign. Ask before you eat. The customer’s power will help minimise the threat to the seas.

Her only disadvantage, as a campaigner, is her proficiency. Decades of lobbying have furnished her mind with a thesaurus of soundbites that she can reproduce automatically, almost without feeling. Some phrases are designed for kids. ‘The ocean is the big blue engine that drives the planet.’ Some might easily be turned into songs. ‘Trawling is like using a bulldozer to catch humming birds.’ Some might already have been turned into songs. ‘The ocean touches us all. Even if you’ve never seen the ocean or smelled the ocean or felt the ocean, it touches you. Every breath you take, every drop of water you drink. Drain the ocean, dry it out, and you have a planet that’s as hostile to life as Mars.’ At times, her speeches have the simplicity and balance of great political rhetoric. Imagine Ronald Reagan savouring the cadences of this: ‘For the first time in all of human history, there is a species that can disrupt the nature of Nature. And that’s us. Our primary focus beyond anything else should be: hold the planet steady. Make sure that the earth works in our favour.’

Only when I mention ‘subsidies’ does she react with genuine emotion, with real pain. She shudders. ‘Subsidies are killing the livelihoods of fisherman by killing the livelihoods of fish. We’re taking too much out.’

Hollywood is waking up to the cause. ‘Leonardo di Caprio is a supporter,’ she says. ‘Daryl Hannah, the original mermaid, she really understands. She started swimming and diving when she was seven. Ted Danson is totally committed, Chevy Chase. And James Cameron.’ She knows the director well enough to have joined him aboard a Russian Mir submarine to celebrate his birthday. His upcoming film — working title, Blue Avatar — promises to bring the issue to worldwide attention.

The next crisis for Her Deepness isn’t wildlife but mining. ‘China has the technology to go to 7,000 feet and extract polymetallic crusts and deposits associated with hydrothermal vents using what are, basically, deep-sea bulldozers. These systems are full of unique forms of life. They’ll take everything.’ But that’s a fight for another day. ‘Just remember,’ she says, leaving me with best phrase in her collection, ‘vote with your fork.’

Comments