What Radio 3 needs is a musical version of Neil MacGregor. The director of the British Museum and now a stalwart of Radio 4 is an intellectual powerhouse but his talks on radio are so clear, so crisp, so deceptively easy to follow that he draws you in and makes you feel that you too can understand the world in the way he does, with his enormously broad vision and his deep understanding of the way things connect.

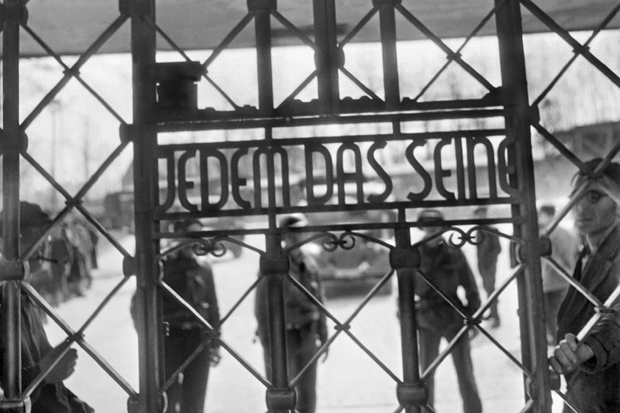

His latest series, Germany: Memories of a Nation, has for five weeks now been giving us these wonderful bite-sized insights into the history of that still-young country, taking a particular object and then using the image, with all the different meanings it might contain, to examine an aspect of German history, sometimes in a national, political sense but just as often from the point of view of the individual and their human story. Last week for instance one episode was devoted to the words blazoned across the entrance to the Buchenwald concentration camp from 1937 until 1945, using them as a jumping-off point to discuss the extermination policies of the Nazis.

‘Jedem das Seine’ (or ‘To each what they are due’) could only be read by those who were inside the camp and had watched the gates being closed behind them, MacGregor explains, as he walks through the gates on a sunny day filled with birdsong, closing them with an audible clunk and looking back. ‘What began here in cruelty and injustice in 1937 led to the destruction of cities …and the killing of millions.’ The dissonance between this now-peaceful setting and the reality of the blood that lies beneath the earth was palpable. ‘No words can carry adequately such brutality and such suffering,’ says MacGregor. ‘There can only be silence.’ And there is silence, seconds of it, an emptiness of sound that chillingly echoes the emptiness of place.

MacGregor has such an understanding of radio as a medium, pacing his words with a deliberation that ensures he extracts from them their fullest meaning, and recognising that sometimes silence is the best way to convey what he wants us to see in our mind’s eye, to hear and to comprehend. Of the words, he reminds us that Elie Wiesel and Bruno Bettelheim would have seen them every day as they walked back into the camp after a day of hard labour. You could read them simply as a threat, a ghastly warning. They were, though, once ‘noble’ words: Luther quoted them and Bach set them to music as a cantata. The sign itself was designed by a camp inmate with an aesthetic skill, elegant and bold in a ‘beautiful, dancing font’. ‘How can these different components of the German story come together?’ MacGregor asks of us, as a challenge almost, a warning that we, too, are going to have to think things through, to explore their full significance.

This series of 15-minute talks (produced by Paul Kobrak and now available to listen to when you have time) has not been arranged chronologically but has sought to create a tapestry of knowledge, of understanding, encouraging us to think about what the world looks like for a nation of such recent origin, whose frontiers have fluctuated so wildly throughout the centuries. Monday’s episode was dedicated to a rough-hewn handcart now in the German Historical Museum in Berlin. It was dragged from Pomerania into what we now think of as Germany at the end of 1945, piled high with bedding, clothes and food, by one of the 14 million Germans who were displaced and forcibly resettled at the end of the war, leaving their homes and most of their belongings behind them. Fourteen million! MacGregor knows how to make a dramatic impact with a single object. That number is many more, he says, than were resettled after partition in India; here, in the heart of Europe, less than 70 years ago.

The 15-minute one-off essay has always been a mainstay of the Radio 3 schedule since its earliest days as the Third Programme (and long before the now-fashionable TED talks on the internet). Radio 4, too, now has its Four Thought slot, a ‘thought-provoking’ talk before an audience in which the speaker is invited to air their passion. On Wednesday we were given an inspiring quarter of an hour by Claire Collingwood, an award-winning dancer who since she was 14 has been unable to stand without crutches (she suffers from osteoporosis). At first, she explained, she thought they would only be temporary. She ‘wanted to be fixed’. In 2005, though, she experienced ‘an epiphany’ after meeting a choreographer who suggested to her that she could use the upper-body strength she had acquired to create unusual dance movements. It became obvious that her hard-won abilities enabled her to move in ways the superfit able-bodied dancers could not match, creating performances that were very different but just as compelling. Why, she asks now, would she not want to be disabled?

Comments