Anyone who thinks opera singers and orchestral players are overworked should spare a thought for the Mariinsky Opera on its trek round England and Wales this week. After Prokofiev’s Betrothal in a Monastery in Cardiff on Sunday, the whole caravan rolled up at the Barbican in the shorter — but not exactly lightweight — first version of Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov. And by the time you read this it will have added Shchedrin’s The Left-Hander and (in Birmingham) the first two instalments of Wagner’s Ring, plus, for the chorus (not required in The Ring till Sunday’s Götterdämmerung), two concerts of Russian sacred music in London and Cardiff.

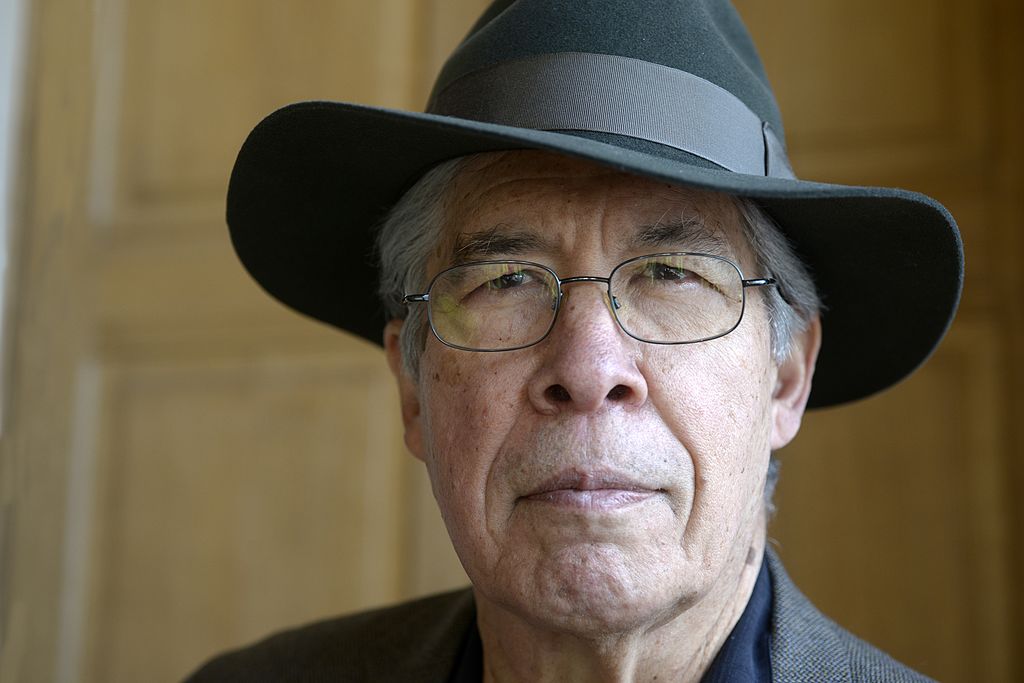

The mad genius behind this odyssey is of course the Mariinsky’s musical director Valery Gergiev, who is conducting all the operas and, for all I know, hypnotising the singers into performing under conditions that would give most voice teachers a tic douloureux. Gergiev creates the impression that his hectic itineraries survive on a knife-edge of timing. He was 15 minutes late for the Prokofiev, and by no means prompt with the Musorgsky. Yet there was nothing chancy about the performances. Prokofiev’s brilliant Russification of Sheridan’s Duenna went like a dream from start to finish, with superb singing and playing and a well-organised semi-staging. There were traces of weariness in Boris Godunov. But these were mere specks on the surface of a revelatory performance of this fascinating but problematic masterpiece.

In opting for the original 1869 version, Gergiev was perhaps making a play for rarity value — not easily achieved in London these days. But while it reduces the cast and duration, it creates problems for the singers. Musorgsky first came to Pushkin’s drama after trying to set Gogol’s comedy Marriage as a syllable-by-syllable prose opera, and something of the same approach survives, much softened, in the first Boris. It’s an austere affair virtually without set numbers and largely devoid of female characters, love interest, and all the other trappings of conventional opera.

Probably for this reason (rather than politics or religion) it was thrown out by the censors. Musorgsky promptly rewrote it, adding the revolution and Polish scenes, complete with ballet, prima donna and love duet, splicing in some folksy set pieces for the girls (including the Innkeeper’s song, which Gergiev naughtily included on Monday), and cutting out some of the best bits of ‘dialogue opera’, as Musorgsky called it.

These episodes give marvellous opportunities for singing actors, but add work for company performers used to the revised score. The Kremlin scene alone, in which Boris reacts to news of the Pretender by hallucinating the bloody image of the murdered Tsarevich, is half an hour of only partly familiar music with many traps and possible wrong turnings. It’s also, it must be said, less exciting, if more concentrated, than the more colourful revision. Mikhail Kazakov, a svelte, young-looking Boris, made powerful capital out of his altercation with Evgeny Akimov’s irresistibly malevolent Shuisky and the ensuing breakdown, and he was good, too, at St Basil’s, face-to-face with Andrei Popov’s marvellously simon-pure, dry-voiced yurodivy (holy fool), a scene that never fails to bring tears.

Mikhail Petrenko took similar advantage of Pimen’s thrilling extended Chudov monastery scene, turning in an instant from solemn old chronicler to vivid storyteller as he related the infanticide at Uglich and the capture of the murderers. But he also exposed the weakness of this version, in its tendency to overshadow the soon-to-be Pretender Grigory (the excellent Sergei Semishkur), who has a couple of brief solos here, a few lines in the Inn scene, then disappears from the opera of which he is the evil genius. Musorgsky remedied this imbalance in the new Polish act. In the original we have to make do with Grigory’s excommunication in absentia at St Basil’s.

There are other anomalies, some of which remained. Varlaam — here the brilliant but tiring (after Prokofiev) Sergei Aleksashkin — has only the Inn scene; Boris’s daughter Xenia (Anastasia Kalagina, a star soprano) has an exquisite but different five minutes, then vanishes; her brother, Fyodor (the lovely Ekaterina Sergeyevna), hangs around a bit but with little to sing: later Musorgsky wrote him/her a pair of charming songs.

So the original has an inchoate feel, along with its purity of intention. But the power and intensity are already present, and Gergiev missed nothing of this in his discreet, contained direction, which brought out many details of Musorgsky’s once-reviled orchestration that one misses in the pit. The choir (with boys from Tiffin School) was secure rather than exciting: their scenes ideally need the stage. But, even with music stands and a certain necessary choreography of metal chairs, there was no shortage of music drama on offer.

Betrothal in a Monastery, for anyone who missed it at Glyndebourne a few years back, will have been a real find. When he read Sheridan’s libretto in 1940, Prokofiev called it ‘champagne’; and certainly his score bubbles like an uncorked bottle of fizz. The plot is conventional enough: elderly father tries to marry lovely daughter off to rich old fish-merchant but is thwarted by her lover, brother and, less typically, duenna (we are in Seville, as usual), who wants the fish-merchant’s cash for herself. But the music has the lyrical flow peculiar to the Prokofiev of Romeo and Juliet, plus the wit and pace of Love for Three Oranges 20 years before.

The performance was as near flawless as one could imagine, with a cast too good overall to single out, and immaculate direction from Gergiev. No wonder voices were tiring by the end of Boris. In every sense this has been a company tour.

Comments