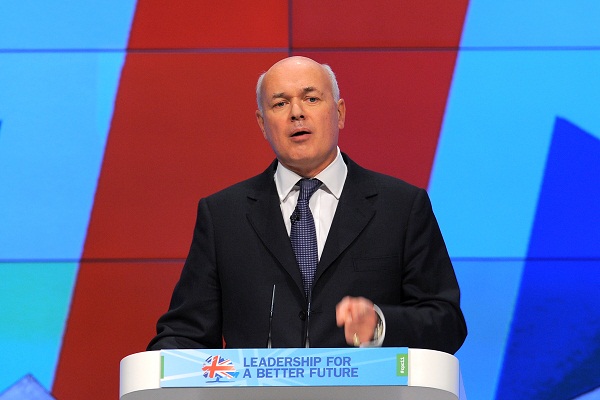

The problem about relative poverty is precisely its relativity. The child poverty index, which measures whether a family’s income is below 60 per cent of the average, is a case in point; when incomes go down, bingo, so does child poverty. Which means that one sure fire if controversial way to improve the Government’s child poverty record would be to drive down everyone’s earnings. Iain Duncan Smith, Work and Pensions Secretary, made just this point yesterday when he made a speech about whether the definition should be rather wider than it is.

‘As we saw last year,’ he observed, ‘when the child poverty level dropped by two per cent – a fall in the median income may lift a family out of poverty on paper. Yet at a closer look, real incomes did not rise and absolute poverty was unchanged. For the 300,000 children no longer in poverty according to the official statistics, life was no different.’

Well, quite so. This brings us to Mr Duncan Smith’s wider point, viz, that child poverty should be measured in all manner of ways which may not be entirely income-related. Family breakdown plainly has a proven impact on a child’s wellbeing – ditto whether he has two parents around in the first place, and whether those parents work and whether they are riddled with debt. Education and decent schooling matter; so does criminality in the area where he grows up. You could of course argue that some of these quality of life elements are related to income – if you weren’t poor, you wouldn’t be living in a poor area, for instance, and you’d be less likely to fall prey to loan sharks. But in general his point holds good. The official child poverty measure is a bit of a blunt instrument, which sets an arbitrary target that can distort overall social and fiscal policy. So, Mr Duncan Smith is launching a consultation to decide whether the measure should include other factors than income.

Of course, he’s right; there should be a wider, more discriminating measure that sets store on some of these other things that affect a child’s wellbeing. It doesn’t stop the Government using the existing way of doing things as well; I think we can cope with two measures of child poverty, don’t you? – one relative to income, the other giving a broader idea of wellbeing, of the ways children aren’t flourishing.

But these indices aren’t neutral, are they? They drive government spending one way or the other. Famously, the last Government set, and missed, its target of halving child poverty by 2010/11 but the effort of trying to achieve it had a profound effect – it resulted, according to Mr Duncan Smith, in an extra £170billion in spending on benefit payments. In other words, targets skew spending choices. As the Institute of Fiscal Studies observed in a study of child poverty:

‘But fiscal redistribution is not costless. There is an inescapable trade-off between increasing redistribution and strengthening financial work incentives. And a pound spent on benefits is a pound not spent on other things which might improve children’s lives more cost-effectively in the long run, such as education, health or social services (or indeed a pound spent on completely different objectives).’

So what would be the spending implications of IDS’s move to include, say family breakdown, in his child poverty index? One could be to give added impetus to the drive within the Tories to meet their manifesto commitment to give tax breaks to those couples who are married or in civil partnerships. So, there could be a transferable tax allowance between couples which would benefit families with one earner. I ought to confess an interest in all this: I’m my family’s earner; my husband doesn’t work outside the home at present (though he will); we don’t, therefore, subcontract the care of our children to au pairs and child-minders. In normal families, I may say, the gender roles would be different but either way, children benefit from the arrangement. A transferable tax allowance would make my life, and that of lots of married couples, easier. It wouldn’t be expensive to administer.

Fiscal favouritism for married couples and civil partners was a distinctive Tory proposal, and you can’t say that about much government policy these days outside welfare and education. So Iain Duncan Smith is onto a good thing here. If his consultation results in a new measure of child poverty, one that measures whether a poor child’s parents are married, it will give added impetus to the campaign to treat marriage favourably, not neutrally. It would, as it happens, benefit the middle classes, not just the poor, but that’s not an argument against, is it?

Comments