Kuniyoshi

From the Arthur R. Miller Collection

Royal Academy, until 7 June

Sponsored by Canon

The Royal Academy is making something of a reputation for staging exhibitions of Japanese printmakers: the current Kuniyoshi show follows on neatly from Hokusai (1991–2) and Hiroshige (1997) and adds considerably to our understanding of the genre. There hasn’t been a major Kuniyoshi show in England for nearly 50 years, and he is certainly one of the less well-known of the great Japanese print artists. Master of an unexpected versatility and variety of subject, Kuniyoshi was also possessed of an originality that stands out even among such talented contemporaries.

The son of a textile dyer and largely self-taught, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) was one of the last great artists of the Edo period in Japan, when the country was governed in the name of the emperor by a censorious military dictatorship. Samurai warriors were a fact of life and Kuniyoshi cornered a market with action-packed warrior prints and illustrations to tales of Chinese brigands from the classic adventure story, ‘The Water Margin’. In this culture of heroes, his powerful and imaginative designs found great favour. Thankfully he was not content simply to churn out images of derring-do, and experimented successfully with other subjects. Among these were landscape, beauties, the theatre and comic cuts. Cuts literally, because the technique of woodblock printing involved the cutting out from cherry wood of his designs, originally drawn on paper with brush and ink.

The process is quite complex, involving a ‘key’ block printed first in black, followed by a separate block for each extra colour (usually five). The size of the blocks was determined by the width of a cherry tree trunk, which resulted in the frequent use of diptychs or triptychs to achieve a more panoramic spread of image. Kuniyoshi, who was interested in European art, adapted Western ideas of perspective and cast shadows for his designs and made impressive use of them in his triptychs. This is seen to particularly good effect in ‘Mitsukuni defies the skeleton spectre conjured up by Princess Takiyasha’. Reading from right to left, the correct way to view a Japanese print, the giant skeleton rears and looms, forcing its way through the reed blind which forms a powerful diagonal across the image, extending through all three panels. An immensely powerful and arresting design.

Kuniyoshi designed some 10,000 prints in his life, no small achievement, of which the RA shows more than 100 fine examples. The first room includes cabinets containing the tools of the trade: inks, blocks, cutting and gouging implements, together with a couple of sketchbooks. Nearby is the skeleton spectre, alongside images of heroes wrestling with, respectively, a giant octopus and a monster carp. Here, too, is the more whimsical and immensely decorative ‘Phoenix and Lobster’, set amid swirling waves. (Prussian blue was a favourite and distinctive colour in the printmaker’s vocabulary.)

The second gallery, or long room, concentrates on the warrior prints, which I personally find less interesting, though the clarity and power of the designs are undeniable. In one image, stylised thunderbolts drop like an angular zigzagging net over a warrior and the monster he has slain. In another memorable print, the great Gojo bridge arches through all three panels of a triptych, while in the ‘Last Stand of the Kusunoki Heroes’, a storm of arrows slices across from the right in an inspired design which must be one of the best here.

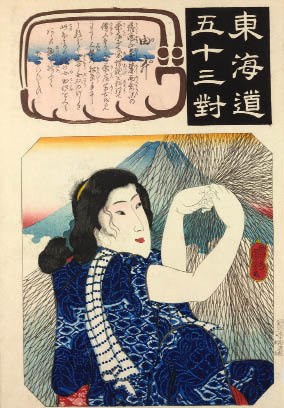

The third room, given over to Beautiful Women, contains altogether less inventive work, more repetitive and stylised, yet even here there are marvels. Look at the extended W-shape of the old plum tree with its intricate branching and flowers, or the vertical shuttering of summer rain. Women depicted weaving or mending a net are also of interest. But on the whole I was more enthralled by the landscape room which comes next, particularly by the red sprigging of fallen maple leaves on the autumn torrent. What a sophistication of pattern — entrancing. As they like to view the moon or cherry blossom, so the Japanese go in for viewing the autumn leaves. These civilised rituals punctuate their lives and offer moments for the contemplation of beauty. Those of us who rush from one task to the next do well to take note.

The last room focuses on theatre and comic images. My favourite here is ‘Sparrows impersonating a brothel scene’. Kuniyoshi was forbidden to depict courtesans by the publishing regulations of 1842 (there’s censorship for you), but got round it very wittily by drawing the girls and their clients as libidinous sparrows. The triptych of Kabuki actors dressed up as turtles getting tiddly on sake is almost as good. The so-called comic erotic work comes as something of a disappointment after all this invention. We are always told how important Japanese prints were for reinvigorating European art in the 19th century (especially in the work of van Gogh and Manet), and here you can see why. In terms of design, they are difficult to beat. This is a marvellous collection, lovingly assembled by Professor Miller, and now generously donated to the British Museum. A highly enjoyable exhibition.

Comments