Just before I started to read this book I had been immersed in the letters written by Jewish merchants based in Cairo from the tenth to the 12th centuries describing the trade they conducted across the Indian Ocean all the way to the Malabar coast. These letters are written in a difficult cursive Hebrew script and in a Judaeo-Arabic dialect, so one needs greater expertise than I possess to read them in the original.

It was therefore with what was almost a sense of dejà vu that I encountered Joseph Sassoon’s fascinating account of the rise and fall of the Sassoon family, from the beginning of the 19th century to the disappearance of their trading name in 1978. Rare mastery of letters and business accounts written in Judaeo-Arabic — this time from Iraq rather than Egypt — has enabled him to write an intimate history of a Jewish family whose commercial successes and fabulous wealth have often been compared with that of the Rothschilds — with whom eventually they intermarried

Several Jewish families in France, Germany and even Tsarist Russia were admitted (though not necessarily welcomed) into the ranks of the aristocracy because of their skill and success as bankers. The Sassoons were not bankers but merchants, whose business methods reveal an uncanny continuity via the Jewish India traders of the Middle Ages back to the ancient Sumerians trading with India around 2000 BC.

The family argued that opium was no worse than tobacco, and even placed a poppy on their coat of arms

They understood the importance of working as a family, and had the instinct about when to invest, when to sell and when to hold on to goods that most successful entrepreneurs possess. Saleh Sassoon had been chief treasurer to the governor of Iraq; but, threatened by the political convulsions of the waning Ottoman empire, he fled Baghdad east to Persia in the 1820s, after which his son David moved to Bombay. Some of the family stayed on in Baghdad, and Joseph Sassoon ruefully admits that it is from this more modest branch that he descends.

He looks at his distant relatives dispassionately and does not cast a veil over activities that even at the time were regarded as controversial. For, once settled in Bombay, the Sassoons gradually became masters (and in the case of a remarkable woman director, Farha, mistress) of the enormously lucrative trade in opium to China. Facing criticism from both the British and Chinese, the Sassoons defended their business, arguing that for most users opium was no worse than tobacco. They even placed a poppy on their coat of arms.

Here, too, there are striking resonances across the centuries. The recent involvement of the Sackler family with the selling of opioids has led to demands that museums and libraries named after them should be renamed. Yet, just like the Sacklers, the Sassoons were exceptionally generous philanthropists. The author describes the hospitals, schools, libraries and synagogues they built in and way beyond Bombay. Early generations were extremely devout: Sassoons travelling deep into the Chinese interior would bring along live chickens to be slaughtered according to kosher rules. But over time their adherence to Jewish ritual became more relaxed. Sassoon women married into the English aristocracy, most famously Sybil Sassoon, Marchioness of Cholmondeley. Sir Victor Sassoon, in the mid-20th century, popped into the Liberal synagogue in London during the great Yom Kippur fast, but popped out again to have lunch with a friend.

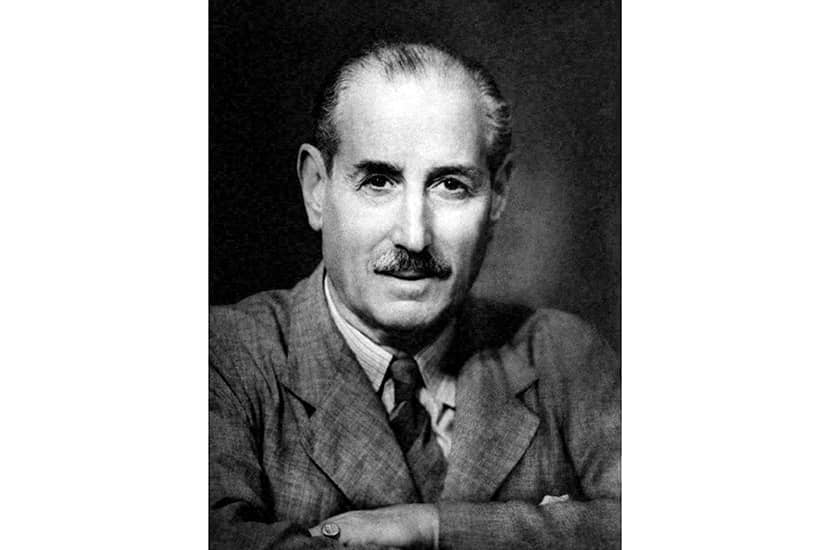

This process of gradual acculturation characterised the Jewish trading families of the 19th century and was particularly marked among the Sephardic and eastern Jews, who, after living mainly under Islamic rule in the Ottoman empire, Morocco and Iraq, became heavily involved in trade with Britain and within the British Empire. English was spoken, not Arabic or Ladino, and European clothing was adopted. Sir Albert, in the early 19th century, was happiest speaking Arabic; his grandson Sir Philip, who died in 1939, was an MP and junior government minister who, on an official visit, admired Iraq in a detached way but expressed no interest in exploring his family’s roots, which by that time some Sassoons seem almost to have found an embarrassment. Siegfried, whose mother was Catholic, was even less interested.

Some members latched on to a newly minted myth that the family had originated in Toledo, among the ancient Sephardic elite, which would have been more respectable in contemporary eyes. But, despite the author’s use of the term, they were not Sephardic Jews — that is, of medieval Spanish descent — but Mizrahi, ‘eastern’ Jews, from an even more ancient community deported to Iraq after Nebuchadnezzar seized Jerusalem in 586 BC.

In his book Ornamentalism, David Cannadine explains how within the British Empire official respect for local elites cut across racial divisions. The Sassoons benefited from this outlook and were as conscious of caste as their Indian neighbours. They did not associate with the ‘Black Jews’ of the Bombay region or the ancient Jewish communities of the Malabar coast. They were a closed group, thinking of themselves as neither Indian nor Iraqi. From the mid-19th century they increasingly wanted to think of themselves as English, and acquired town and country houses to prove the point. Even the buildings they charitably erected in India were in the neo-Gothic style. In the 20th century, horse racing took the fancy of Sir Victor, who famously quipped: ‘There is only one race greater than the Jews and that’s the Derby.’

Whether in India or England, the Sassoons put more and more energy into magnificent entertainment. They became part of the court circle of the future Edward VII. The author does not report any examples of visceral anti-Semitism directed at the family of the sort circulating in France after the Dreyfus trial. The Countess of Warwick wrote that her set resented the presence of Jews in the Prince of Wales’s circle ‘not because we disliked them… but because they had brains and understood finance’. The Spectator added a quizzical touch when it reported on the elevation of Albert Sassoon to a baronetcy in the New Year’s Honours list of 1890: ‘The rise of this Jewish family in England has been remarkably rapid, as they were still quite recently strictly Indian Jews, almost native in their way of life.’ But it conceded: ‘Much of the Central Asian trade is in their hands.’

So it appeared in 1890; but the winds had already shifted. Despite the victories of Britain and France in the Opium Wars, the bottom was falling out of the opium market — indeed, one solution the Chinese found to the outflow of silver the trade caused was to cultivate opium themselves. The Sassoons, now divided into two competing companies, had to diversify. An opportunity was provided by the American Civil War, which cut off supplies of plantation cotton and opened up the chance to exploit sources of cotton in India and elsewhere. Before long, the Sassoons began to invest in machinery for the cotton industry, which they shipped out to India, working with their Parsi neighbours, members of another entrepreneurial minority, the Zoroastrians.

But the upheaval of the first world war prompted even bigger changes. Victor Sassoon shifted the centre of gravity of his operations east to the Bund in Shanghai. His enormous Cathay Hotel was just one of his property enterprises in the city — until, that is, the Japanese invasion. He is still remembered in Shanghai for the help he gave Jews from central and eastern Europe who escaped Nazi persecution by fleeing across Asia, putting them up for a while in the hotel.

At the end of the book the author draws comparisons with other Baghdadi families, such as the Kadoories, who built their fortune on the trade of the British Empire. But there is a wider question: how and why Jewish entrepreneurs, outsiders who created worldwide commercial networks, have managed to play such a significant role in economic life over so many centuries. Whatever the answer, Joseph Sassoon has written a very readable, sensitive and original account of a remarkable family, deftly weaving together the history of the business, the history of the family and their place in the wider history of Britain, India and China.

Comments