‘I know our Lord told us to be wise as serpents and innocent as doves,’ muttered a colleague after a waspish College meeting; ‘but, being busy men, some of us find it advisable to specialise.’ I detected that approach in Matthew Parris’s contention, in The Spectator last week, that Christianity, particularly the Gospels, cannot help us prioritise when faced with the vast, terrible refugee crisis. We all want to help, he said, but the teachings of Jesus don’t tell us how to do it.

All right: much popular reaction, Christian included, has been little more than anguished arm-waving. But soundbites are not the real clue. What counts is action. To look no further than my own church, the Anglican chaplaincies in Budapest and Athens have been working with tireless generosity. The Canterbury diocese, close to Calais, has been going the second mile, then the third and fourth. It’s risky to say, ‘Look what we Christians do’; history is littered with our follies and failures. But the early Christians were first in the field of caring for strangers, the poor and refugees, just as they initiated public medicine and education. We’re still doing it.

This still begs Matthew’s question about priorities. But there should be no puzzle. The gospels pick up the ancient Israelite narratives of hope: hope for a coming king who would do justice for the poor, defend and deliver the needy, overturn oppression and take pity on the weak. ‘Remember the poor,’ St Peter reminded St Paul. By the end of the second century, the Roman authorities didn’t know exactly what Christianity was, but they knew what bishops were: pesky nuisances, always banging on about the plight of the poor.

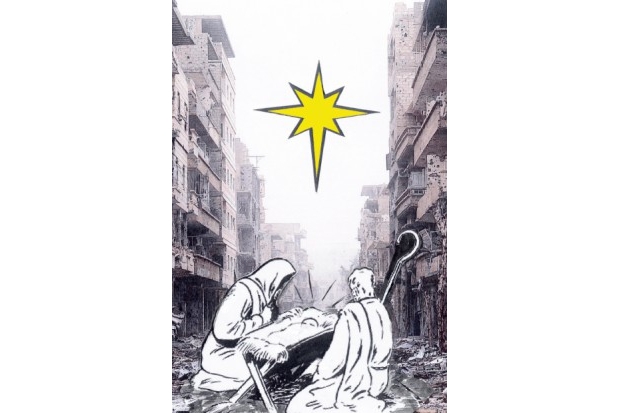

Hardly surprising: because the Bible is one long story of exile and refugees. Starting with the expulsion from the garden, it continues with slavery and wilderness wandering. It reaches a climax in the Babylonian exile; then a greater one with Jesus himself, a refugee in infancy, then with ‘nowhere to lay his head’ until he slumps on the cross. St Paul finds himself adrift in the Mediterranean, washing up on an island where the locals welcome him and he joins in with the work in hand. Homeless wandering is part of the world-out-of-joint into which, in the biblical story, God himself came, to identify with its plight and so to rescue and transform it.

The gospels are not, then, a compendium of detached moral maxims for individuals. Jesus’ sayings find their meaning within the larger story about new creation struggling to be born. ‘Supposing God was in charge,’ Jesus was asking, ‘might it not look like this?’ – as he healed the sick, fed the hungry, rebuked the arrogant, told sharp-edged stories, wept with distressed friends, and (not least) confronted cynical authorities. ‘God’s rule’ poses its challenge to nations and cultures, not just individuals.

Matthew Parris’s dismissal of key gospel sayings is a kind of hare-and-tortoise sophistry. You can ‘prove’ that the hare will never overtake the tortoise but we all know he will. Thus, despite his prevarication, nobody who truly wants to follow Jesus will have much difficulty discerning occasional apparent exceptions to the Golden Rule. Mature wisdom will recognise that ‘loving your neighbour as yourself’ may mean volunteering for a local charity rather than leaping in your car to solve the problems alone. The Good Samaritan story is not impatient with the idea of ‘community’; it opens it up to embrace the whole world.

What about ‘render to Caesar’? A quick and sharp answer to a dangerous question. Jesus’ wider teaching about ‘God’s rule’ makes it clear that he cannot have meant what we think of as a ‘church/state’ split. In Matthew 28 he claims ‘all authority in heaven and on earth’.

This brings us to the other key point. Along with the absolute priority of looking after the weakest and poorest, the church has a specific vocation. One of the tasks Jesus bequeathed his followers is to hold earthly rulers to account. This doesn’t mean clever clerical soundbites, still less theologians aping one strand of popular prejudice. It means drawing on the sustained wisdom of the worldwide church, across space and time, to remind rulers (often distracted by the next election or referendum) what they are there for. Back once more to the Psalms, the prophets and Jesus’ vision of God’s Rule. At the climax of the fourth gospel, Jesus confronted Pontius Pilate on the topics of kingdom, truth and power. His followers need to do the same.

Of course, this can’t be done in a crisis. When the house is on fire, you don’t sit down and read four books comparing different types of smoke alarm. But once the fire is put out, you ought then to do the homework omitted earlier. The hugely complex current crisis has many roots. They include the refusal of western leaders to attend either to the irreducibly religious dimensions of the problems or to the ancient Christian wisdom which would have suggested alternative narratives and strategies. Western secularism has instead parodied the Christian mission: imagining we now know how the world works, we claim the right to impose our solutions from a great height. The grossly inappropriate reaction to 9/11, led ironically by two professing Christians, Bush and Blair, has given a generation of Muslims excuses for supposing that ‘being Christian’ means ‘killing Muslims’. That was compounded by the misreading of the ‘Arab Spring’, as though toppling a few tyrants would automatically result in peace, love, flower-power and liberal democracy. Wrong stories lead to wrong solutions and unintended consequences.

The present crisis, like 9/11 itself and the Holocaust before it, is another sign that our present western civilisation has shaky foundations. Our self-enclosed consumerist dreams have a cost, and the bill is now being presented. Of course, the Syrian crisis comes on top of anguished debates about other migrations, from the subcontinent, from Eastern Europe, from Africa and elsewhere. These raise other important questions. But that shouldn’t get in the way of immediate response, and subsequent wise reflection.

One gospel passage might have caught even the sceptical eye. In Matthew 15 a Syrian mother appeals to Jesus on behalf of her desperately sick daughter. The disciples try to shoo her away. Even Jesus (who had hoped for privacy) challenges her. She answers him back, and Jesus heals the girl. The relevance is obvious.

By themselves, the serpent offers cynical cunning, and the dove naïve oversimplifications. We need proper balance, not specialisation. Let’s put out the fire by all means possible. Then let’s study the books about smoke alarms.

Tom Wright, a former Bishop of Durham, is Professor of New Testament Studies at the University of St Andrews

Comments