Is intellectual self-confidence a good thing? Ed Miliband was teased in parliament by David Cameron for claiming to possess it, and teased again by Lord Finkelstein in his notebook for The Times. ‘I know he thinks he is extremely clever,’ Cameron sneered at PMQs. Lord Finkelstein refers to a book that claims that intellectual self-confidence is a curse because it leads to wrong decisions. I disagree. We argue in the leader of this week’s Spectator that Miliband is very confident about bad ideas, and Cameron lacks confidence in good ones. More’s the pity.

Cameron was being unfair: intellectual self-confidence does not mean thinking you’re ‘extremely clever’. It’s about believing you have the right ideas, and being prepared to articulate and act on them. In my opinion, one of the main reasons that the Conservatives failed to win the 2010 general election (in a recession, against a loathed Prime Minister) was the failure to express a clear idea of what they stood for – and what they’d do in office.

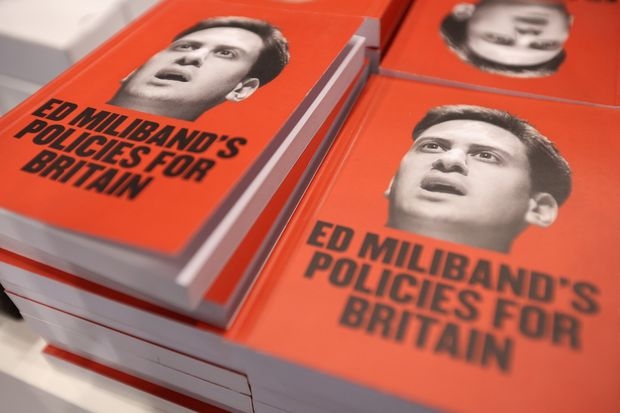

Voters want to know: what’s on offer? Ed Miliband is commendably clear. His founding philosophy is that the market has failed, that the recovery is going wrong by rewarding a handful of people at the top. That the Tories’ blind faith in the market is causing what Matthew d’Ancona has referred to as a ‘Bullingdon bubble‘ rather than a proper, shared recovery. Hence stagnant wages, and the need for something different. Miliband says he’d be a more assertive Prime Minister, he’d step in to correct market failures. For example: he’d impose energy price freezes three-year rent contracts to stop landlords hiking the rent, perhaps renationalize the railways – the list goes on. You can argue that this is very dangerous, but it’s coherent. It starts with philosophy and ends up in action: there is a straight line. That’s what Miliband means by intellectual self-confidence: he knows what he believes, he can talk about it, and plans to convert his ideas into action.

David Cameron, by contrast, shies away from this. Perhaps he believes, as Lord Finkelstein says in the column, that too much certainty is a defect in a leader. I can see Danny’s point, in that voters are unnerved by leaders who come across as ideologues. I’ve heard others (not Danny) make this point in quite heated terms, and behind a lot of it is the old Tory wars. (You’d be amazed, or perhaps you wouldn’t, about how many Tories are still, in their heads, fighting the battles of the last decade, thinking that ‘moderniser’ and ‘traditionalist’ are still useful terms in 2014. Such bizarre sectarianism remains the great Tory curse). Some Tories argue that swivel-eyed certainty kept the Tories in opposition for 13 years, and there is certainly some truth in that the party was hurt by being successfully portrayed as a bunch of zealots.

You can also argue that conservatives reject ideology, and are suspicious of stone-cold certainty. As Lord Melbourne put it two centuries ago: ‘I wish I was as cocksure of anything as Tom Macaulay is of everything’.

But voters do buy into the idea of principle – and a political party that represents a wider movement. The reason that Labour held on to so many seats in 2010 was the enduring strength of the Labour brand. Yes, the party was led by a reviled misanthrope, but the Labour movement was a lot more than Gordon Brown. People voted, then, to protect and sustain Labour values.

Can the same be said for the Conservatives? What are Tory values? The Cameroons are not really comfortable with defining this – so their enemies do it for them. (The latest Labour Party attack video is a ham-fisted attempt to fill this vacuum). In Charles Moore’s biography of Thatcher (p269), he quotes her just before she decided to stand for the leadership:-

‘In an artful interview in the Sunday Express, Mrs Thatcher insisted that “my only wish is to further the Conservative Party and the philosophy upon which it is founded”‘

And who defines that philosophy today? What’s the big Tory idea? I’d say that the Conservative philosophy is richer, deeper, more in tune with modern Britain than the 1970s revivalist stuff being proposed by Miliband. I’d also say that David Cameron is the single best chance that this country has at election time, because he would apply conservative insights that would best address the problems Miliband talks about (and many problems that he doesn’t).

Labour is being admirably clear about its philosophy – and I think it would not hurt the Conservatives to try do the same. You can muddle through an election without giving a clear idea of what you stand for, but as Cameron demonstrated last time, it tends not to work very well. This isn’t about being left, right, traditionalist or modernist – it’s just about being clear. About letting people know what direction you would take the country in. Cameron is always at his best when speaking form the heart; his instincts are sound. All told, Cameron has much to be self-confident about. He has the right ideas, and should talk about them more often.

Comments