During my time in No. 10 as one of Dominic Cummings’s ‘weirdos and misfits’, my team would often speak with frontline artificial intelligence researchers. We grew increasingly concerned about what we heard. Researchers at tech companies believed they were much closer to creating superintelligent AIs than was being publicly discussed. Some were frightened by the technology they were unleashing. They didn’t know how to control it; their AI systems were doing things they couldn’t understand or predict; they realised they could be producing something very dangerous.

This is why the UK’s newly established AI Taskforce is hosting its first summit next week at Bletchley Park where international politicians, tech firms, academics and representatives of civil society will meet to discuss these dangers.

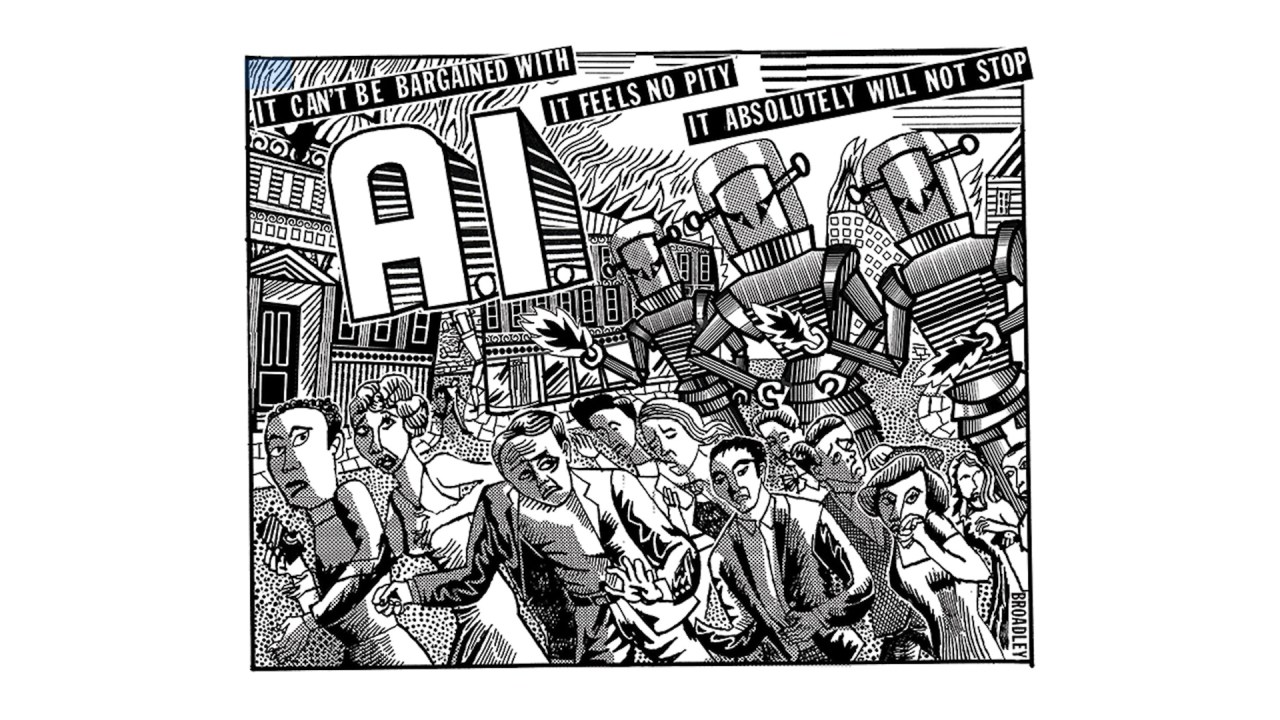

Without oversight, the range of possible harms will only grow in ways we can’t foresee

Getting to the point of ‘superintelligence’ – when AI exceeds human intelligence – is the stated goal of companies such as Google DeepMind, Anthropic and OpenAI, and they estimate that this will happen in the short-term. Demis Hassabis, of DeepMind, says some form of human-equivalent intelligence will be achieved in the next decade. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI (ChatGPT’s creator), reckons he’ll achieve it by 2030 or 2031. They may be wrong – but so far their predictions have usually been right.

So you see the conundrum. AI that has the power to damage society is being created by people who know the risks but are locked in a race against each other, unable to slow down because they worry about becoming irrelevant in their field. Yet, even though they aren’t slowing down, all the major lab CEOs signed a letter earlier this year saying that AI was a nuclear-level extinction risk.

The dangers are real. Two years ago, an AI was developed that could, in a few hours, rediscover from scratch internationally banned chemical warfare agents, and invent 40,000 more ‘promising candidate’ toxins. And as Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei testified to the US Senate in July, Large Language Models such as ChatGPT can already help with key steps in causing civilisation-scale harm through biological weapons.

As superintelligent AI develops the ability to interact with the world without restrictions and oversight, the range of possible harms will only grow in ways that we can’t foresee. Just this week, a letter co-written by two of the three ‘godfathers’ of AI, Yoshua Bengio and Geoffrey Hinton, warned that AI systems could soon plan, pursue goals and ‘act in the world’.

If you went back in time and asked people how humanity should approach creating something vastly smarter than itself, a sense of caution would likely be a central suggestion. Yet as superintelligence comes nearer to being achieved, there are huge financial interests in Silicon Valley for the race to move even faster.

It is concern over the speed of progress that lay behind the British government’s decision to establish its new £100 million taskforce, hoping that it will give the answers to what the UK should do about the looming prospect of superintelligence. The AI Taskforce is modelled on Kate Bingham’s Vaccine Taskforce. But it faces a bigger hurdle than Bingham’s did. When that was launched, everyone knew the goal was to roll out a vaccine to combat Covid. This was something tangible – and obviously there was a sense of urgency that Covid needed to be tackled. There is, by contrast, no consensus among governments about whether AI is a big risk, let alone if states need to regulate its development.

The firms producing AI are not keen on proper outside regulation. They prefer to evaluate themselves with self-selected partners. They refer to this as ‘evals’, which involves the companies assessing the risk of their models only after they’ve been created. Sure, this has some benefits, but it’s retrospective; it does nothing to slow the race, and means there’s no external oversight of what they are creating. As it stands, when (rather than ‘if’) superintelligence is achieved, the technology – and the oversight of it – will be controlled by a few private companies. That’s not in anyone’s interest.

The government should push for more oversight, so that the next generation of AI will not be released without a proper audit of the risks. It should also set up an independent body to appraise them.

Given the political paralysis in the US, and the lack of expertise in other countries, regulation is reliant on goodwill by the tech companies, not on binding rules. This runs the danger of ‘regulatory capture’, whereby the AI companies effectively write their own tests and regulations – marking their own homework, in other words.

At the moment, AI is allowed to grow in ways we can’t understand. That these machines can grow without human input is cheaper, faster, and easier for the firms, but also more dangerous. One suggestion is that the government should control the development of AI through an international collaborative lab, so that there are multiple actors involved rather than a lone company.

Big tech wouldn’t like this, as it would be more expensive and make the work harder. But it would go some way towards stopping things running out of control. The government could also promote the idea of capping the computing power used to train models, so their development ceases being so exponential. The taskforce should argue for enforcing physical security around advanced models, such as implementing ‘kill switches’ to ensure they can’t escape and evolve on their own if they seem to be posing a problem.

The government has done a decent job of being ahead of the curve just by hosting an international summit. But this doesn’t change the fact that there needs to be a global consensus on what civilisational risk we are prepared to take in developing AI – and who should be responsible for making the decisions. These are going to be some of the most important questions of our time.

James W. Phillips is a former special adviser to the prime minister for science and technology. He was a lead author on the Blair-Hague report on AI.

Comments