The Enchanted Island is a baroque concoction at the New York Met which has been widely touted and last Saturday was relayed worldwide to cinemas, a transmission that went less smoothly than any I have seen before, with some sharp variations of volume and a temporary complete breakdown. On the whole, the sound level is very high, as if everyone is singing at the top of their voice; while it’s nice to have ample volume, it is clearly and disconcertingly a misrepresentation. Danielle de Niese, for instance, has a small voice which just about fills Glyndebourne’s house. Here she sounded like a Wagnerian on the make, with coloratura sounding like ‘Hojotoho!’. That could mean severe disappointment, or maybe relief, for anyone who hasn’t encountered her in the flesh and gets to do so.

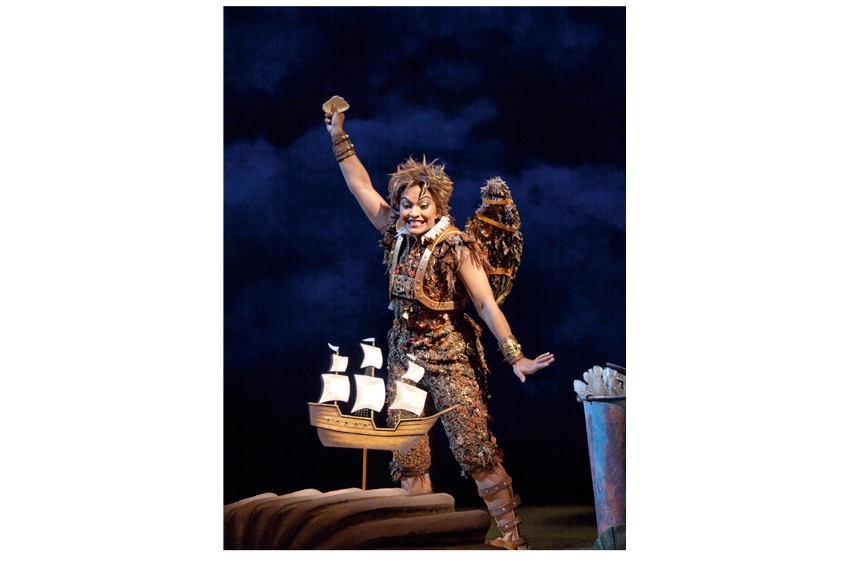

De Niese was playing the pivotal figure, Ariel, in this adaptation by Jeremy Sams of some of the plot of The Tempest and some of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Sams’s idea was that there isn’t enough love interest in The Tempest, so he has Ariel incompetently shipwreck the wrong boat, on which the two pairs of lovers from Dream are on a honeymoon cruise. When they arrive on the island there follows a lengthy series of non-recognitions, mistaken infatuations, and the other ingredients which make me find Dream a tiresome play. Shakespeare’s language isn’t used, with the exception of a few celebrated quotations. One trouble is that though The Tempest might need more love interest — questionable — another two pairs of lovers makes for an awkwardly large cast, and guarantees a chaotic plotline. This in turn leads to an unsteadiness of tone, so that it becomes impossible to decide whether to take some of it seriously and regard the rest as a send-up, or to regard the whole thing as an amiably confusing parody of high baroque opera.

Of course Handel’s operas — and Handel is the composer most heavily raided for this score — are remarkably flexible in tone, as has only recently been realised. He can move smoothly from grief to mischief. The trouble here is not so much movement from one state to another, as uncertainty about how seriously we are to take any state. Though that’s not wholly accurate — it is clear that Prospero and Sycorax are to be taken at face value, though with Joyce DiDonato hamming it up to the last degree that wasn’t always easy.

With such a large cast, and the whole of baroque opera and for that matter oratorio to raid — go to the Met’s website and you can see listed the sources of all the music — one envisages some pretty intense jockeying for who had how many arias, and which they were to be. They were clearly chosen with the singers available in mind, as they would have been in the 18th century, so it isn’t surprising that everyone, or everyone but one, had music to show off their voice to best advantage. The exception, alas, was Placido Domingo, inserted as Neptune, wearing an astonishing proportion of the contents of an ancient male godswear store, and singing in a language invented and I hope patented by himself. He can speak English perfectly well, as the inevitable intermission interview showed. But when he sings it he drops not only syllables but also whole words, and distorts others in the weirdest way — he threatened, in the interview, to sing two or three more baroque roles.

Opinions will differ sharply about de Niese. I found her, as I always have, intolerably cute and pleased with herself, though it would be churlish to deny that she has quite a lot to be pleased about. And, as organiser of the general chaos, she was given every chance to throw her glances and her weight around. David Daniels as her master Prospero gave the work dignity, producing fantastic rich countertenor tone, and looking superb: a pity he was given some of Prospero’s finest lines to speak at the end, which he did badly. Joyce DiDonato showed that she is the unsurpassed mistress at present of coloratura, mainly used for vengeful purposes; but she can be, and was, also inward and affecting. Caliban is played as a wholly sympathetic figure, and Luca Pisaroni made him a movingly grotesque figure.

Everyone else was adequate, and William Christie, who played a large role in the work’s inception, accompanied stylishly. I would be interested to see more projects of this kind, since there are many operas that are mainly tedious but have the occasional magical aria needing to be rescued. That might be done with Italian operas of the first half of the 19th century, too. I doubt whether The Enchanted Island is destined for a life independent of this lavish production, even by Met standards decadently luxurious. And the first part lasted for an interminable 100 minutes, wandering aimlessly. The second contained more interesting moments, and was more teleological, but still begged to be described as an exotick and irrational entertainment.

Comments