Moonlight is, in fact, a traditional story about identity, and finding out who you are, but it has rarely been better told, or more achingly, or while navigating a subject that hasn’t come up much at the cinema, if at all. (Being black and gay.) True enough, everyone expected La La Land to win best picture at the Oscars, but it’s Moonlight that deserved the award – and every award going (aside from the one that’s been put aside for Annette Bening). I liked La La Land well enough at the time, but someone please make it go away now.

The film is written and directed by Barry Jenkins, as based on Tarell Alvin McCraney’s semi-autobiographical but never performed play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue. It’s set in the poor Liberty City projects in Miami, where both men grew up, and was filmed in just 25 days. This does give it a pressure-cooker intensity of the kind that, say, isn’t found in movies where white people endlessly mansplain jazz — what can I say? I liked it well enough at the time, but now it’s so annoying — yet it is also a film of the utmost delicacy. The love that dare not speak its name does not speak its name, but there is desire, feeling, yearning, tension in every frame.

The story is presented as a triptych starring three actors playing the same character, Chiron, at different ages. So it’s Chiron (Alex R. Hibbert) as a little boy, Chiron (Ashton Sanders) as a teenager and Chiron (Trevante Rhodes) as a young man in his twenties (which is the biggest shock; prepare yourselves). Jenkins did not allow the three actors to meet during filming because he didn’t want them to imitate each other, so they don’t, and neither do they bear much physical resemblance, yet the performances are so extraordinary that there is no question it’s the same soul throughout. How Jenkins did that I don’t know, but it may explain why he’s a film director and I am not.

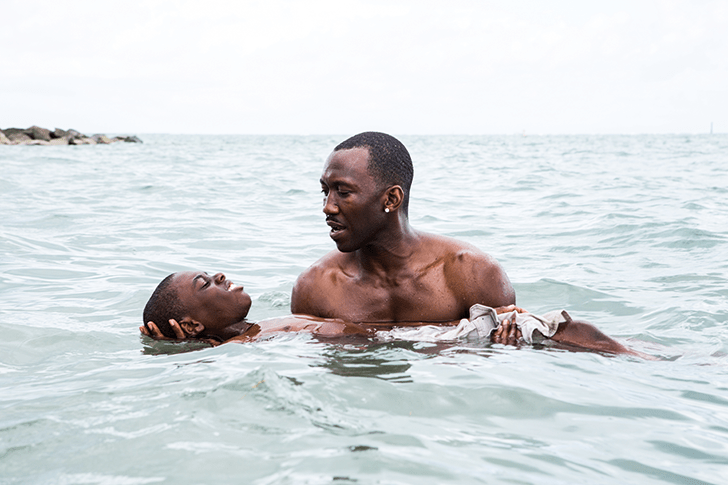

When we first encounter Chiron he is a withdrawn, watchful, near-silent child. He is vulnerably different in some way. He knows it. The other kids know it, chase him, throw bottles at him. He lives in the projects with his mother (a superb Naomie Harris). She’s a crack addict but she isn’t the usual stereotype. She is layered. There’s the drugs and the pain but you also feel the love she has for her son. (This isn’t The Wire.) Chiron is taken under the wing of the local drug dealer, Juan (Mahershala Ali; formidable). What does Juan want with the boy, we are thinking, while expecting the worst. But Juan isn’t a stereotype either. Drug dealers can do love, softness, humanity. There’s a breathtakingly beautiful scene where Juan teaches Chiron to swim. ‘What’s a faggot?’ Chiron will ask Juan. Oh God, how’s he going to reply? Here, I will only say that while homophobia is, indeed, prevalent in black male culture, not every black man is a homophobe. Important lesson.

There is, throughout, only one other significant person in Chiron’s life, and that’s his schoolfriend Kevin, whom we also see at the three ages (Jaden Piner, Jharrel Jerome, André Holland). Kevin can no more express his feelings for Chiron than Chiron can for Kevin but we feel the attraction between the two from day one. Chiron remains passive, quite annoyingly so, until the teenage section, when he suddenly snaps and returns as Chiron #3. It’s a shock. Has he betrayed his true nature for a certain kind of manhood?

This is a deeply compassionate film that not only does astounding work on the being black, being gay front, but is also about anybody who feels they exist outside the world they’ve been born into. A traditional narrative, that, but it’s rarely been better told.

This is an updated version of Deborah Ross’ review of Moonlight, which originally appeared in the Spectator last week

Comments