We already know that Britain has a massive sick-note problem but we did not, until today, know just how large. Every three months, the ONS surveys 35,000 people and uses the results to guess how many (for example) are not working due to long-term sickness. That figure had been 2.6 million. But it has today been revised upwards by 200,000 – equivalent to the population of Norwich or Aberdeen – to 2.8 million. The chart of those too sick to work, already one of the most alarming in UK economics, now looks even worse.

The Labour Force Survey – the tool that statisticians use to work out employment, unemployment and economic inactivity (those out of work and not looking for it either) – has been ‘reweighted’ because population estimates had undercounted how many people live here.

This matters because the UK is still suffering massive worker shortages (almost a million vacancies) which has been sucking in immigration. So the sick-note culture is creating a vacuum in the heart of the labour market, increasing net migration and resulting pressures. This is projected by the DWP to get much worse: we have compiled its forecasts in the Spectator data hub. One of the charts is below. The shaded grey area will be the challenge confronting whoever wins the next election.

The good news is that there are more people in employment than previously thought (as a result of a bigger population). The official unemployment rate was also revised down to 3.9 per cent, having previously been estimated at 4.2 per cent. However, the actual number of people unemployed and economically inactive went up too. Employment went up from just under 33 million to just over, and unemployment went up by 30,000. The biggest revision was for inactivity, rising by nearly half a million people to 9.3 million Britons out of work and not looking for it either.

Britain’s workforce is getting bigger and sicker

The revised population estimates showed Britain to be a younger country than we had previously thought too. These changes, along with an increase in the number of women in the figures, drive the increase in unemployment and inactivity, since more and more young people are studying rather than filling jobs.

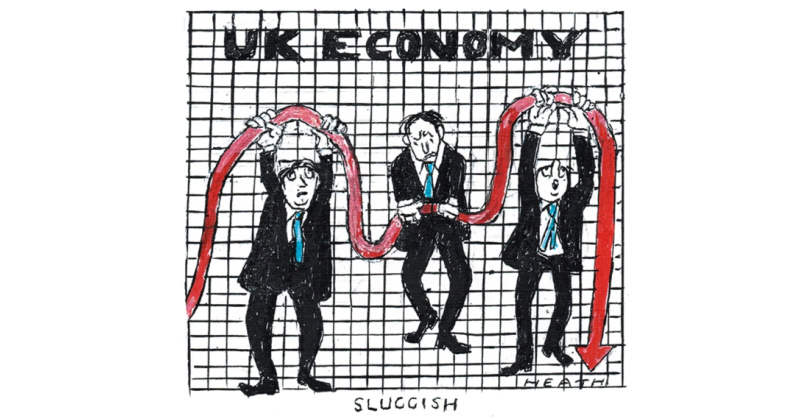

These figures are not what the government wanted to hear. There had been hope within the Department for Work and Pensions that revisions to the LFS would lead to positive news on Britain’s’ labour market – which has seen one of the slowest recoveries in the developed world – but the opposite has happened.

Rate setters in the Bank of England will be keeping a keen eye on any further revisions to the jobs market figures too. If the employment rate is indeed falling, as the corrections suggest, then the labour market is not loosening fast enough for the Bank to quickly cut interest rates. Right now, markets expect to see cuts to rates in the spring. If unemployment rates remain low and vacancies remain high, we can expect that to change.

Hopefully these revisions – which will be included fully in next week’s job market figures – will put an end to months of uncertainty and mistrust in the ONS’s estimates. Whilst this reweighting was long planned, the Labour Force Statistics were stopped in their entirety last Autumn because the data had become so unreliable. Response rates had sunk dramatically and, as has been shown today, the population underpinning them skewed old and male when the labour force was getting proportionally younger. During this time Britain has existed in a dangerous era of economic uncertainty. You cannot make decisions about which levers to pull if you don’t know how many people are in work, looking for jobs or out of the labour market completely. Let’s hope this time the figures are watertight.

Comments