MPs are now in recess. Again. Cue plenty of moans about them escaping the zombie parliament and jetting off on holiday. There’s not much you can do about the former, but the latter is not, as any MP will angrily remind you, quite true. If you’re a type with a big majority who is a bit fonder of the Westminster game than you are of your constituents, then a holiday might be an option. But at this time of year, MPs are more likely to be found canvassing for the European and local elections, or holding extra constituency surgeries to catch up on time lost to Parliament.

The Conservative whips have told MPs, via one of their many text messages that they send throughout each day, that they are expected to visit Newark three times before the by-election, and that few exemptions will be allowed. Some MPs are planning to exempt themselves from this. One tells me that ‘I have no desire to be promoted, so I don’t need to get extra points on their little list of visits.’

But what’s life like for those plugging away back in their own constituencies? I wrote a blog a while back on the weird things parliamentarians are asked for help with, but more often than not, constituency surgeries are quite dispiriting affairs, as most people who come along for a meeting with their MP are in a dreadful tangle, often as a result of something the state has done to them.

I recently accompanied Labour MP Tristram Hunt on one of his constituency surgeries in Stoke-on-Trent. It was a textbook surgery, held at a small trestle table in a huge gymnasium. A rank of spinning bikes watched as people filed in and out to discuss their problems with Hunt. One or two had come for the wrong MP, and so their meetings were very short indeed: parliamentarians can only deal with those who live in their constituencies, and pass other cases along to the relevant colleague.

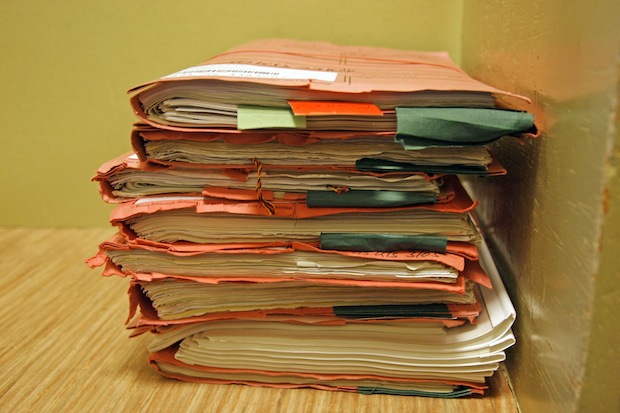

Most arrived with letters, bills and documents from court hearings, all setting out the ways in which they’d somehow been wronged, mostly by the state. There’s something intensely dispiriting about the mess in which our clunky and inefficient system of government departments, quangos, schools, local authorities and NHS bodies can leave perfectly innocent ordinary people. And that mess is embodied in these piles of papers. The piles often aren’t small piles, either. They’re terrifying, confusing piles of papers that have been stuffed into plastic folders or carrier bags. The MP and his constituency workers have to unravel their story, which doesn’t often set out the real problem in the first few paragraphs, and those piles of paper, before trying to intervene on their behalf. Children excluded from school because they have learning difficulties, housing problems, benefits stopped and then re-started at the wrong level: it’s an MP’s job to try to right some of those wrongs, if they can.

This is just another one of the jobs that MPs do week in, week out, that barely ever get reported on. But after watching Hunt talk to his constituents in Stoke, I realised that one of the charges levelled at MPs – that they are part of the ‘Westminster bubble’ – is quite unfair. Most of them meet more ‘ordinary’ members of the public than those who level that charge ever will. And many of those members of the public they meet are in acute distress: you’re less likely to make an appointment with your parliamentarian if you’re rolling in dosh. Some of the most acute observers of the political scene are MPs in marginal seats because they view it through the eyes of their constituents who they spend as much time with as they possibly can in an attempt to hang onto that seat at the next election. But their colleagues with safer seats do still leave the bubble to work week in week out with some of the saddest examples of our messy government and our messy society that you can find. No wonder they grow a little grumpy when everyone jokes that they’re disappearing off on holiday during the parliamentary recess.

Comments