It’s 2022 and classical music is, again, dead. It’d be surprising if it wasn’t. In 2014 the New Yorker published a timeline by the industry analyst Andy Doe showing the precise chronology of the decline and fall. Ageing audiences in the 21st century, the gramophone in the 20th, the dangerous new technology of the pianoforte in the 1840s: all, in their time, were considered proof that the rot was terminal. Doe traced the root of the problem back to a papal bull in 1324, giving new potency to Charles Rosen’s remark that ‘the death of classical music is perhaps its oldest continuing tradition’.

Anyway, the fatal blow this time is the Great Awokening. The symptoms are allegedly widespread in university music departments: students who can read music are being made to check their privilege, and Beethoven, if he hasn’t been cancelled as a sonic rapist, has been relegated to the status of ‘above average composer’. As described in these pages by Ian Pace a few months back, it sounds chilling. One feels pity for the scholars who’ve found themselves on the wrong end of some musicological Maoist struggle session — and a profound relief that off campus, among the non-peer-reviewed civilians who actually perform and enjoy classical music, it has practically no effect at all.

The financial realities of most UK classical promoters put revolution far outside their price range

What, none? Log off Twitter and scroll through the upcoming concert listings: there’s Vaughan Williams in Manchester, Verdi at Covent Garden and — yes —Beethoven in Birmingham. Cancellation should be made of sterner stuff. In reality, it’s difficult to overstate just how little effect academia has upon the way that British performing companies operate. Even genuinely useful work goes largely ignored: Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations was heavily doctored by its 19th-century publisher. Musicological research restored Tchaikovsky’s original, strikingly different version in 1956, but seven decades on, you’ll almost never hear it performed live.

No, boringly enough (and Covid restrictions aside — the one form of cancellation that poses a genuine threat), it’s largely business as usual in the concert hall. No pitchfork mob is likely to topple Mahler any time soon, and the financial realities of most UK classical promoters — overstretched, understaffed and rarely more than half a season from insolvency — put revolution far outside their price range. Despite public arts subsidy, a healthy box-office income remains vital for most organisations. Market forces do the rest, and as a non-musicologist once put it, the facts of life are conservative.

It’s not that concert programmes are immune to change. Classical music, as a profession, skews soft-left: decision-makers are aware of current debates, and generally aspire to do the right thing. They’re also acutely aware of what their audiences are prepared to pay for. A ten-minute sinfonia by a forgotten 18th-century violinist is inexpensive and listenable, and if the composer’s mother was a slave, social justice (in its current definition) has been served. Probably 99.9 per cent of all music ever written goes completely unplayed, regardless of the composer’s race or gender. It’d take a mean-spirited music lover to object to more variety, and anyway, there’s still Brahms after the interval.

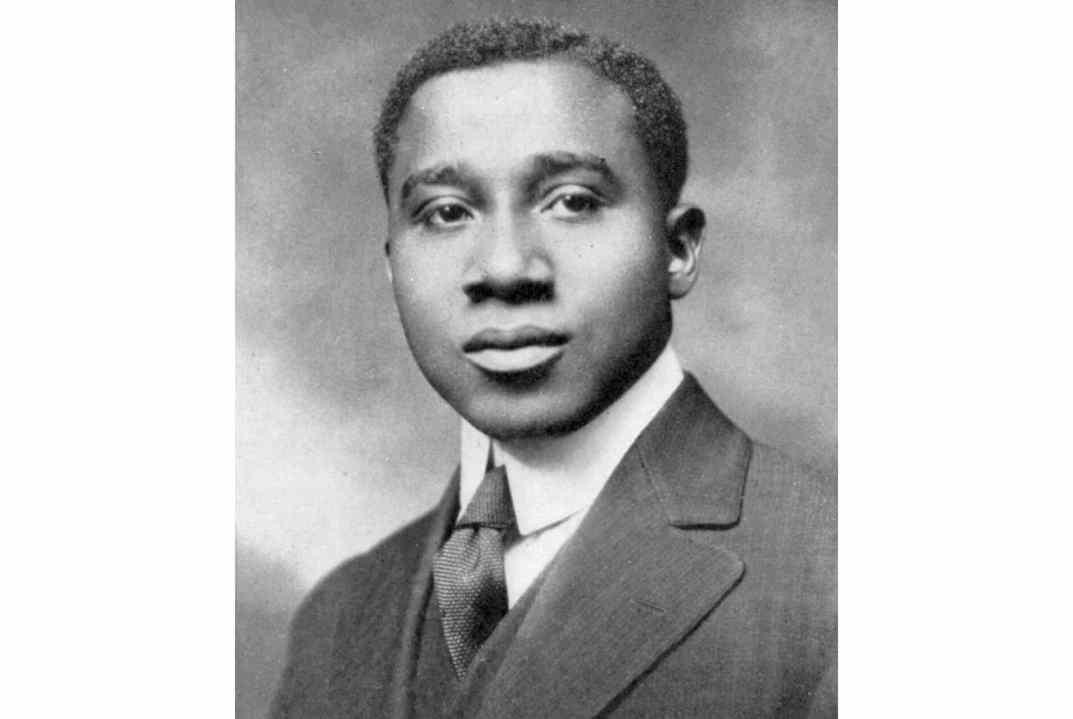

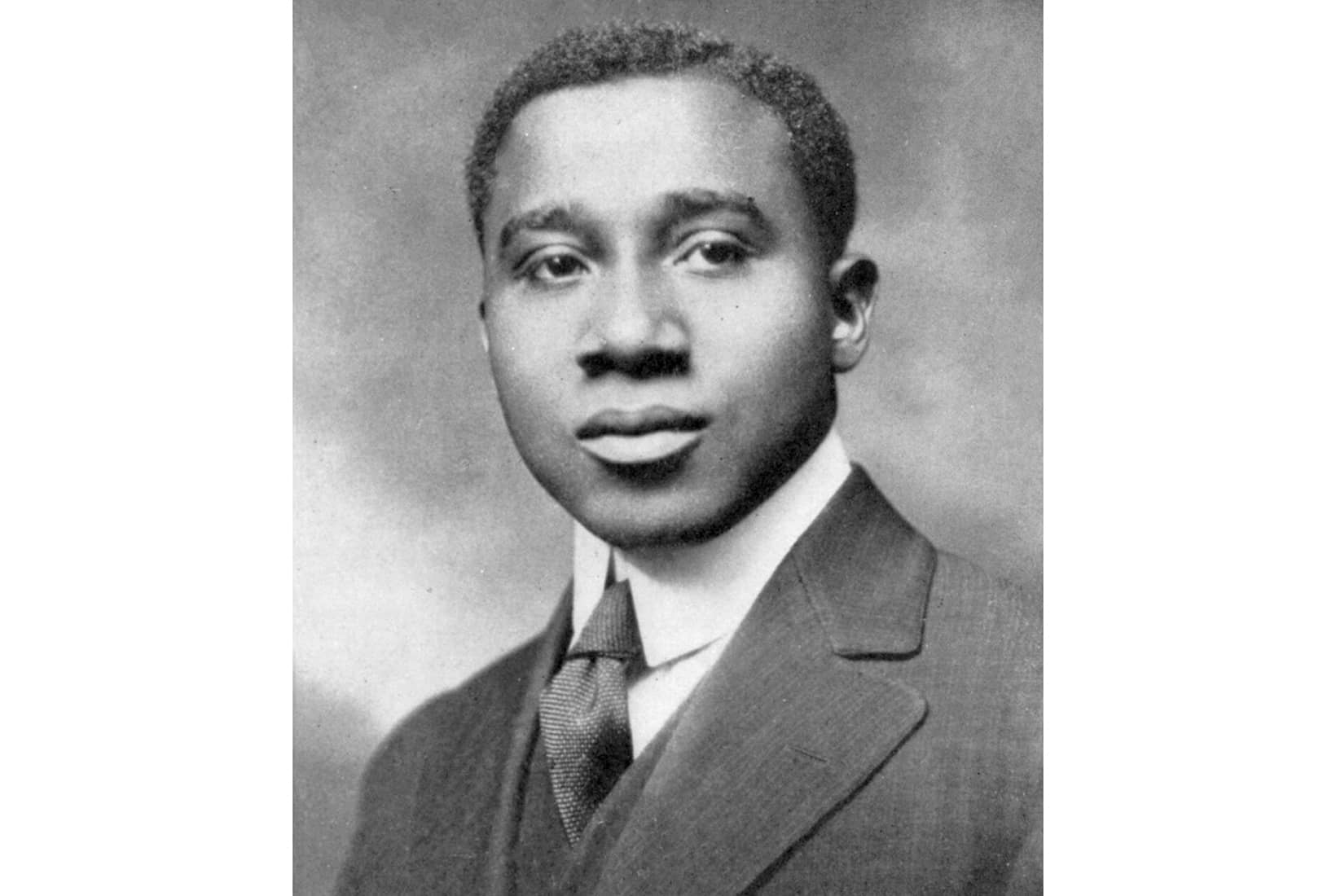

So there’ve been a few of these recent additions to the concert repertoire. Cynics might laugh at the way that, in the wake of #MeToo, orchestras suddenly discovered that a couple of short, royalty-free pieces by Lili Boulanger could be dropped into concerts for instant gender balance, and how, since BLM, Boulanger’s stock has dipped while the mixed-race American symphonist Florence Price and the Edwardian Englishman Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (whose father was from Sierra Leone) have risen. It’s tempting to bristle, too, at the way history is fudged to suit the preferred narrative: the notion that Coleridge-Taylor (whose choral music sold out the Royal Albert Hall between the wars) was a marginalised figure is — to put it mildly — a bit of a stretch.

But the end result is that some worthwhile music gets a second chance — and more often than not, finds a welcome, too. Curiously enough, in the looking-glass logic of identity politics, music that would once have been dismissed as unchallenging is now deemed progressive. It’s noticeable that the cause of gender balance has generally been addressed through approachable (and copyright-free) 19th-century Romantics like Clara Schumann or Louise Farrenc, rather than spiky postwar modernists like Elisabeth Lutyens or Priaulx Rainier.

Meanwhile the music of Price, Coleridge-Taylor and Robert Nathaniel Dett (whose Parry-like cantata The Ordering of Moses is being performed in Birmingham next month) would be considered positively old-fashioned in any other context. If a radical agenda has put engaging melodies, warm harmonies and sprawling Romantic symphonies back at the cutting edge, that, surely, is an unintended consequence to make conservative hearts leap. Come for the Beethoven, stay for the Coleridge-Taylor. You might find that you rather like the sound it makes.

Comments