Nothing more gladdens this reader’s heart than a book that opens up an interesting and underexplored historical byway. Well, perhaps one thing: a book that opens up a historical byway that turns out to be a complete catastrophe. On that count, A Merciless Place more than delivers. Here is one of the great colonial cock-ups.

It all started with a question that resonates to this day. When your jails are overcrowded academies of crime, and the respectable public lives in fear of what it imagines to be a violent criminal underclass, what do you do with your surplus convicts? Ken Clarke not yet having been thought of, conventional opinion in the 18th century was: ship them overseas and let them be somebody else’s problem. Yes, it hurt. Yes, it worked. For years, Britain had been cheerfully exporting to America such criminals as it didn’t care to imprison and couldn’t quite bear to hang.

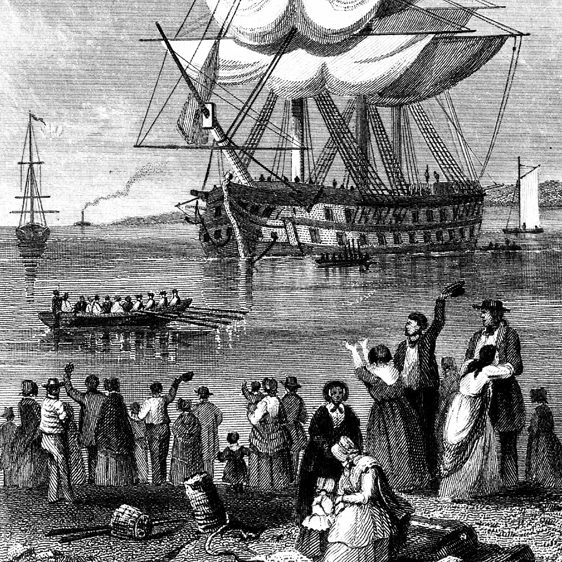

Among other inconveniences, however, the American Revolution more or less put the kibosh on that racket. So with London’s jails overflowing, and prison hulks offering an agreeably inhumane but essentially limited solution, His Majesty’s Government started casting around for somewhere else to send its undesirables.

As we all know, it finally settled — and with some success — on Australia. Emma Christopher, however, turns her attention to Britain’s abortive first attempt: a series of experiments in the second half of the 18th century with sending convicts to West Africa. Initially, they went as soldiers — in the form of the 101st and 102nd Independent Companies — and later there were schemes to send them as labourers or colonists.

Ostensibly the 101st and 102nd were there to grab Dutch possessions along the coast, but the soldiering was really a dodge. Because the British slaving forts in what was then Senegambia were run by the Royal African Company, personnel couldn’t be imposed on them by the Crown, and most of the men of the Royal African Company didn’t want the convicts there. They feared that the natives would lose respect for the white man if they met his convicts, and speculated that the whole tense business of running a slaving post — not knowing whether you would at any moment be attacked by slaves, overrun by locals or shot at by the troops of rival colonial powers — would be made no easier by adding hundreds of criminals to the mix.

On the whole, though, the convicts behaved rather well. Such behavioural shortcomings as they did have — a tendency to contract tropical diseases and die in agony, or run away and join the Dutch army instead — were understandable. No: the real horrors were their commanders.

The Mr Kurtz of this particular account is Kenneth Mackenzie: a Highland Scot who never wanted to go to Africa in the first place. Deep in debt, and having lost most of his property after his wife divorced him for his whoring, Mackenzie had raised a company of men in the hopes of fighting for the King in America and restoring his fortunes in prize-money. To his humiliation, all the halfway fit men in his company were promptly requisitioned to fight in America and he was packed off to Africa, his company’s numbers made up with knock-kneed London convicts.

Mackenzie made a bad start, militarily. His assault on one Dutch fort went hopelessly wrong, and he fled half a mile back behind his own lines to order a retreat. He sulkily refused to help garrison other British possessions, preferring to consolidate his men in his own stronghold and set about trying to make money for himself. He kept most of the rations and entitlements he was supposed to distribute to his men, punished them savagely for insubordination, and set them to labour in the fields alongside native slaves.

He even put one of the convicts — a raffish con-man called William Murray (who, weirdly, went by the alias Kenneth Mackenzie) — in charge of the garrison at a fort along the coast, a decision not exactly conducive, shall we say, to traditional military discipline. He went on illegally to capture two neutral trading ships — private plunder, essentially, under pretence of an act of war. Worse, given that the British forts relied on good relations with the local tribes to operate, he treated the natives with open contempt, plundering their goods and destroying their property as he saw fit. Eventually they rose up, beat seven bells out of him, removed his trousers and ran him naked out of town. The civilian governor of Cape Coast Castle, Richard Miles, was driven to despair.

Mackenzie really overstepped the mark, though, when he fell out with the aforementioned William Murray and clapped him in irons. Murray escaped from jail, and on recapturing him, Mackenzie decided to execute him. Was it the lack of legal process that was most to be regretted, or the fact that he did so by strapping him to the front of a nine-pound cannon and forcing a fellow soldier at gunpoint to set it off? To bury him, his comrades-in-arms had to scurry below the fort walls collecting the blown-apart bits of him — ‘his kidnies, and his liver and lights, as plain to be seen as ever anything was in the world’.

One of the sourest ironies of this story is that, having finally been shipped back to Blighty and thrown in jail for Murray’s murder, Mackenzie was eventually pardoned and freed. As Emma Christopher points out, none of the wretches who served in appalling suffering under him had done anything like such evil. The details of the crimes for which each convict was transported are among the most poignant things here; young Thomas Limpus was sentenced to seven years transportation to Africa, for instance, for the theft of a single cambric handkerchief worth tenpence.

This is such an interesting tale that I did find myself wishing A Merciless Place a better book. It is terribly clumsily written: filled with double-edged swords, awful truths, boiling blood, frenzies of indignation, ultimate sacrifices, chickens coming home to roost and such like. Some of the metaphors deserve a place in a trophy cabinet: ‘clinging tentatively to the precipice of oblivion’; ‘the apex around which the legal system turned’; ‘Mackenzie again raised the stakes of devastation’; ‘slowly, like a bleeding wound, Newgate spilled out its constricted guts’.

Defects of style aren’t in themselves defects of scholarship. There’s a fat biblio-graphy and it’s clear that great care has been taken in tracing the stories of these people in close detail through court records and the paperwork of the Royal African Company. There’s a bit more nonsense about ‘destiny’ and ‘tragedy’ than I’d like, though — and if there are sources for character X having ‘mixed feelings’ or the notion that character Y was ‘less relieved… than indignant’ they aren’t given.

Still, the temper of the book — and the degree to which the story carries you over the shortcomings of its telling — is actually best captured by part of its scholarly apparatus. A Merciless Place has a first-class index. Under ‘Mackenzie’, for instance, you glance at the L-M section and see ‘leads attack on fishermen… life before Africa… loses his mind… men refuse to serve under…’ and then in T-U, you find ‘turned out of Mori naked… ungentlemanly vocabulary of… unhappy with portrait…’. Any book that boasts such an index is well worth an afternoon or two of your time.

Comments