To understand the decay of the Labour Party since 2015, look no further than its London youth wing. London Young Labour (LYL) is the Momentum-controlled home of the capital’s under-27 Labour members. It is also a sparkling example of the worst kinds of regressive identity politics popping up on campuses across Britain.

As a 26-year-old Labour member, albeit of a more moderate persuasion than those now running the show, I decided to go along to LYL’s Annual General Meeting last weekend. People talk of Labour as the party of young people. I hoped that the event might make me grow a newfound respect for a party I am quickly losing confidence in. Unfortunately, I left disappointed.

I joined the Labour party after moving to London from Australia six months ago, hoping to get more involved in grassroots politics. I identified as a centrist supporter of the Australian Labor party, which is more moderate than its British iteration, however I thought I could get on board with Jeremy Corbyn’s socialist vision of the party. I reasoned to myself that some of Corbyn’s more left-wing economic policies were perhaps necessary in a country where inequality appeared starker; Australia boasts a higher minimum wage, superior welfare system and higher rate of GDP per capita than the UK. I was also optimistic that Britain’s Labour party was big enough to accommodate a wide range of views.

I was wrong: I was not braced for the bouts of anti-Semitism, bullying and extreme political correctness the party has cultivated. And the AGM made me even more depressed about Labour’s future under Corbyn. It also revealed that the next generation of Labour leaders are set to continue to take the party in the wrong direction.

A series of forgettable speakers, including Faiza Shaheen – the Labour candidate for the seat of Chingford and Woodford, which is currently held by Tory MP Iain Duncan Smith – took to the stage. Next came the elections for LYL’s 2019-20 chairperson and committee. Some of the candidates’ positions offered some glimmers of optimism, particularly when it came to universal credit, where the Tories’ reforms have undoubtedly left people worse off. But on the whole I was struck by how homogenous many of the speeches were. It was also depressing to hear cliches popping up time and again. The phrases “radical socialism” and “intersectionality” sprang forth from the lips of several candidates. More worryingly, so too did talk of the need for Young Labour to run more political education programmes throughout London.

The lack of diverse opinions on show at the AGM makes it clear what form such an education is likely to take. The few other moderates I encountered on the day were as fed up as I was. They said the emergence of Momentum has led to a toxic environment in the group, where dissenting opinions are quickly quashed. This was demonstrated when a man in the crowd called for every Labour MP not backed by Momentum to be expelled. A raucous round of applause – the day’s largest – ensued. I had thought that being a student was a time when you were supposed to examine different ideological positions and openly debate ideas; not so in Young Labour, it would seem.

Another perplexing trend throughout the day was discussion about people who “self-identify” as disabled. When I first heard the term I was confused – on what grounds can you identify as disabled? I’ve always considered disabilities as existing beyond the realm of personal choice or identity.

This kind of strange identity politics was also evident in LYL’s caucuses. Traditionally caucuses are used to group collective interests based on geography or type of employment, however in Young Labour they have been based around ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender and disability status. This seems a fitting example of how Labour’s youth wing has abandoned its traditional set of values for a far more niche set of worries. Instead of characterising mutual interest around economic realities, these young apparatchiks instead frame it on a fluid notion of identity. This is in clear conflict with the socialist values they claim to represent.

Yet this focus on identity politics is sure to backfire when it comes to actually winning over the public. What goes down well at such meetings won’t persuade Labour votes to come out at election time. Instead, it’s likely that such attitudes will only continue to alienate mainstream voters, surely sinking Labour into electoral oblivion. Platitudes about white privilege and gender fluidity simply do not resonate throughout middle England, where elections are won and lost.

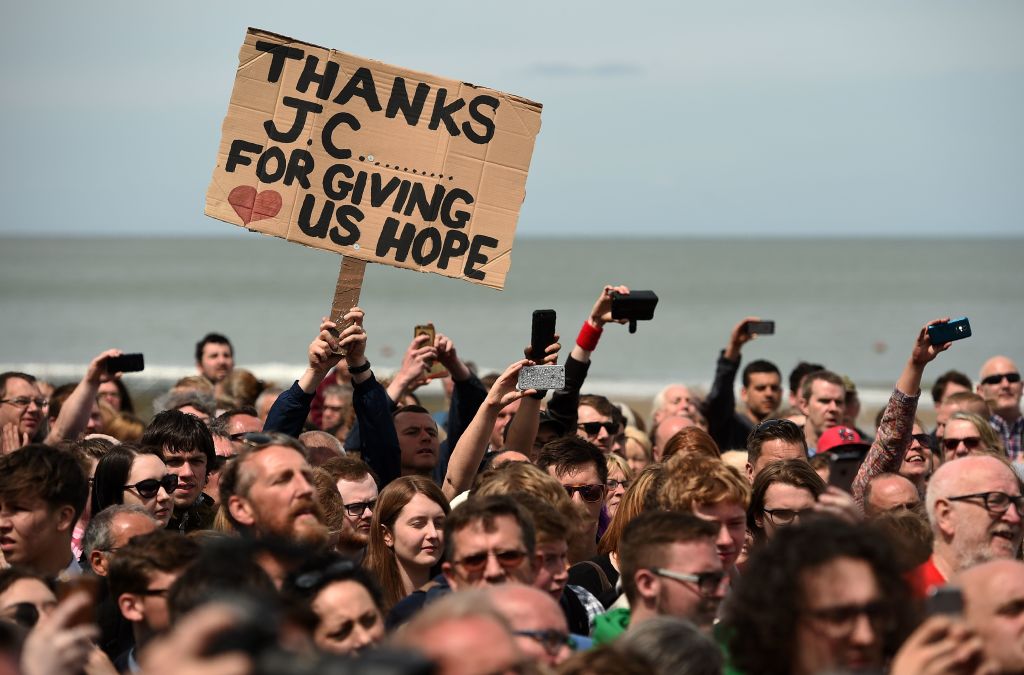

Even though the 2017 snap election has been painted as something of a triumph for Labour, the party actually picked up fewer working class voters than the Tories, despite its slogan of “For the many, not the few”. Statistics from YouGov show that people with a low level of education voted 55 per cent to 33 in favour of the Tories, while the majority of people who work skilled or unskilled manual labour jobs also voted Conservative. It’s true that university educated and metropolitan voters overwhelmingly chose Labour. But by abandoning the concerns of the country’s working class, the party has betrayed its very reason for existence and its electoral viability.

While I hold on to hope that the party of Attlee, Kinnock and Blair will come good in the near future, I’m not holding my breath. If young Momentum members do one day set the historical direction of Labour, then I fear the party will never return to its former glory.

Comments