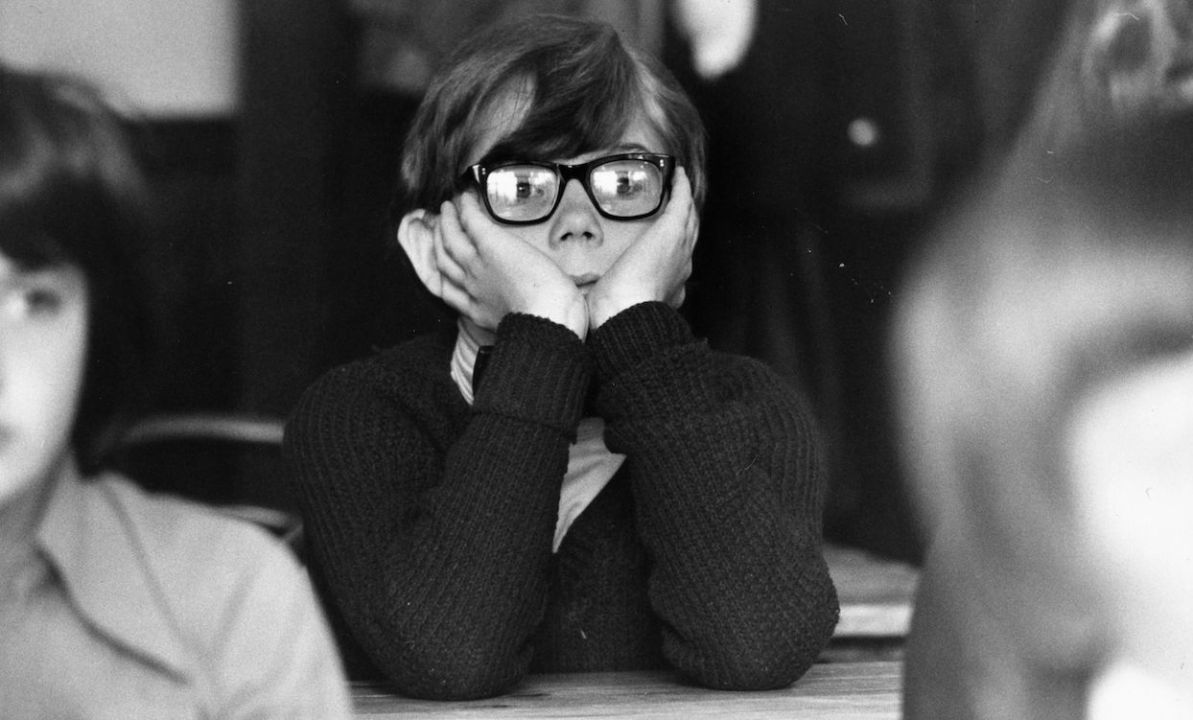

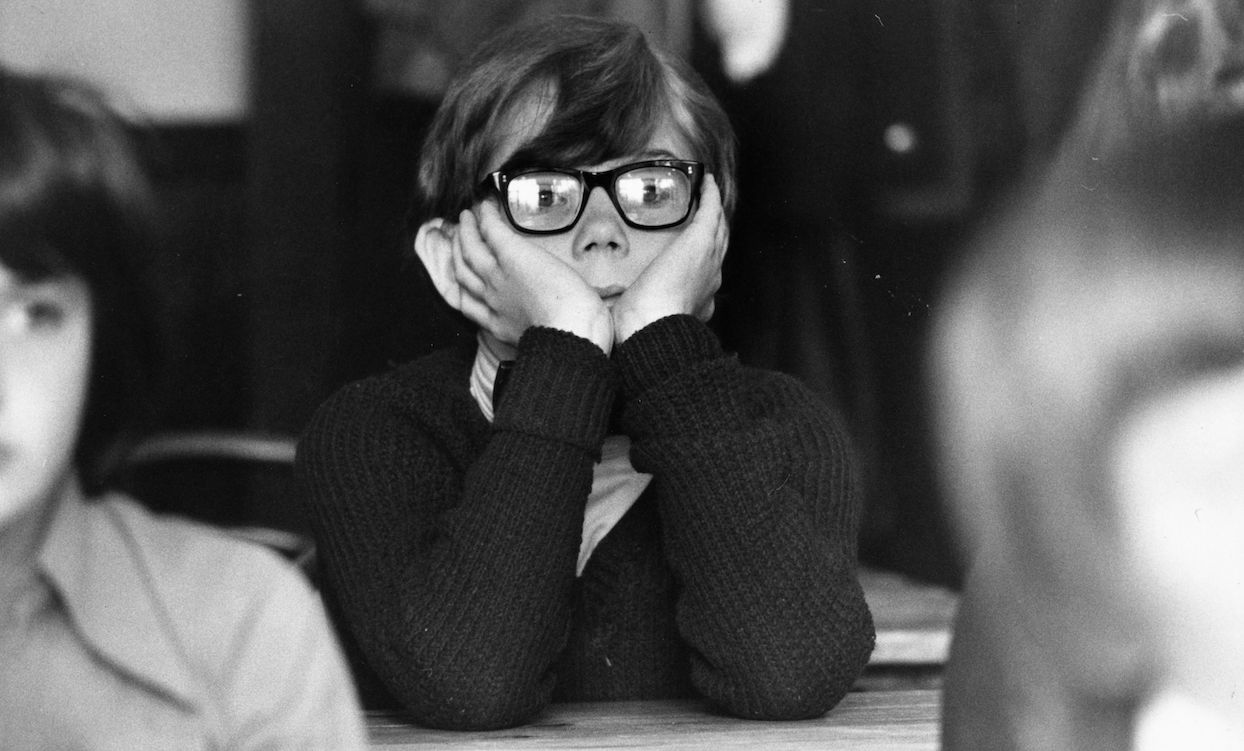

In 1979, I was 11 years old, and I had a quite remarkable teacher. Don’t worry, though – this isn’t going to be one of those anodyne paeans to an inspirational educator that the Department for Education use in their ads to lure people into teaching. In fact, if the lady I’ll refer to here as Mrs G were somehow to be reincarnated and placed in front of a Year 6 classroom of today, Ofsted would have her frogmarched out after about 20 minutes.

She once sent me to the local parade of shops to buy a box of Tampax

Mrs G was a fearsome sight – in her late 40s, as broad as she was tall, squeezed into shirt and slacks, with closely shorn curls. I have no photographic evidence, so I’m relying on memory here. She seemed enormous, but then so does everything to a child. She was an extremely forcefully expressed person with an extremely loud voice, and an extremely broad Ulster accent, reminiscent of the late Reverend Ian Paisley in both its register and delivery.

All this made her stand out in the anonymous Home Counties town that my school was at the unfashionable end of. Everybody was terrified of her. She was the folk devil of all local kids from the age of five. Years before I ended up in her class I’d heard the stories: she made you wee in a bucket rather than excuse you to the loo. If you laughed at her she put a curse on you. She’d killed a boy.

The myths were so extreme, I discovered, because the reality was so vividly eccentric. She had an erratic but wide-ranging spectrum of knowledge, and lessons would suddenly deviate along whatever path her mind had wildly wandered. A black cat at the window was a sign that a child would die; our very commonplace headmaster was an agent of the Pope; ordnance survey maps were unreliable because they’d been tampered with by aliens.

She delighted in reading to us ghost stories and tales of horror, and had a bloodcurdling fund of her own tall tales. She had woken one morning on a camping trip to see an angel hovering over her sleeping bag; the ghost of her father had materialised on the ramp of the ferry to Liverpool saying ‘Don’t leave the old country!’; George Best had been her star pupil back home. When she got annoyed by us clicking the ends of our retractable ballpoints, she told us how, after a crash on a lonely road in the upper Alps, she had been trapped in the wreckage of her car with the dead body of her husband for hours with only a clicking noise for company, and we’d brought it all back. ‘Will you stop with the clicking of the pens!’

She was wont to unscheduled (and I suspect unauthorised) school trips to local sites of interest, in a rattletrap van that backfired, halted, and jerked back to life, and into which children were crammed 20 at a time like sardines.

Like that van, she seemed always to be on the verge of boiling rage, and was subject to what I now realise were frequent diabetic hypoglycaemic attacks – ‘Give me sugar!’ Discipline was maintained mainly through terror, and the very rarely used but always visible threat of Willie Slipper. Willie was a very old plimsoll with a very hard sole that hung on a nail on the wall. She was at her most dangerous when quiet, when after some particularly bad misbehaviour she would wait for the class to subside into terror and then whisper, ‘Fetch me that slipper’.

Being shouted at by her was a mortifying experience. This tended to happen in a prefabricated block shared by each class in the school on a rota basis – once a fortnight – which was filled with practical equipment of all kinds for art, cookery, science, etc, with the futuristic title of The Resource Room. Then, as now, I am hopeless at practical tasks. The sight of the place could reduce me to the tears of boredom that only children cry. I can still feel the reverberation in my bones as she passed judgment on a Danish pastry that was one of my attempts at domestic science. ‘That is like something they would serve up in a concentration camp!’

Even today, when I hear my full name called unexpectedly, I shudder, and no matter who says it in however amiable a tone, it reaches my ears in a Belfast roar. When daft rumours infected the playground, she cleared them up by telling us all, boys and girls, the facts of menstruation. (She once sent me to the local parade of shops to buy a box of Tampax.) We were already up on the facts of life, so she obliged by filling us in on the ins and outs, in some detail, of gay sex.

She was fantastic. I learnt more from Mrs G than any other adult. Maybe not on the subjects on the set curriculum, but about the strangeness and struggle of life, the unfathomable edges and contradictions of people.

During the 11+ exam, as I struggled over an anagram, which had the clue ‘Freedom’, she leant over my desk and whispered ‘Liberty!’ And liberty was what she gave me. But I can’t end there. As I left the hall she grabbed me by the neck and whispered again, fiercely, right in my ear, ‘Tell anyone I did that Gareth Roberts, and I’ll break your bloody arm’.

Comments