When the vaccine pass comes into effect later this week, I will not be able to enter a bar or a restaurant. I will not be able to visit a museum or go to the movies. I will not be able to watch a live sports event or attend a music concert. I will not be able to take a regional train or walk through a shopping centre. And I will no longer be able to swim in my local pool or jog around the municipal running track.

I could, of course, become a functioning member of French society in an instant if I went to my nearest vaccination centre, rolled up my sleeve and received a third jab, what the French call a ‘rappel’. But I’ve weighed up the pros and cons, read articles such as the one in The Spectator by Dr Steve James, and decided that two vaccines will suffice for me. As the doctor eloquently stated, ‘turning to coercion or overturning bodily autonomy marks the point where we begin to fail as a free society’.

I was also helped in reaching my decision over the new year when, staying with my (triple-vaccinated) parents in England, they both succumbed to Omicron. I eluded the grasp of the virus despite its highly contagious nature, or perhaps I’m one of those lucky asymptomatic people. Either way, as a lifelong non-smoker who has always exercised regularly and eaten healthily I have confidence in my immune system.

With energy prices rising and inflation soaring, Macron’s grandiose vision for France set out in 2017 has not come to pass

There may be one or two excitable types who, in reading this, mutter about ‘Mortimer the anti-vaxxer’, the lazy insult hurled at anyone who expresses the slightest doubt about having their arm turned into a pin cushion. I’m not anti-vax, obviously, but I am anti-hysteria, and that is what Macron has turned France into: an hysterical nation. Last week, I returned to France after nearly a month in England. It was like entering another world. One of the first sights to greet me was of an elderly woman sporting what at first glance was a blue beard. On closer inspection it was four masks glued together, two horizontally and two vertically.

It was a pleasure to spend so long in England. I felt a freedom that I haven’t felt for many months, not since before July last year, the month when Macron introduced his Covid passport. That required people to show proof of their double vaccination to enter social venues or proof of a negative test within the last 48 hours. As of this week that option has been removed and a third jab has been made a requirement, despite the fact that Covid cases now appear to be on the wane. France, however, has adopted a different strategy to England. Instead of opening up as infections decline it is clamping down.

Although I won’t be updating my passport, it won’t make much of a difference. Even when I was able to enter such venues having had two vaccinations, I chose not to. There is, in my opinion, something profoundly intrusive and immoral about the requirement to show proof of your health status to drink a beer in a bar.

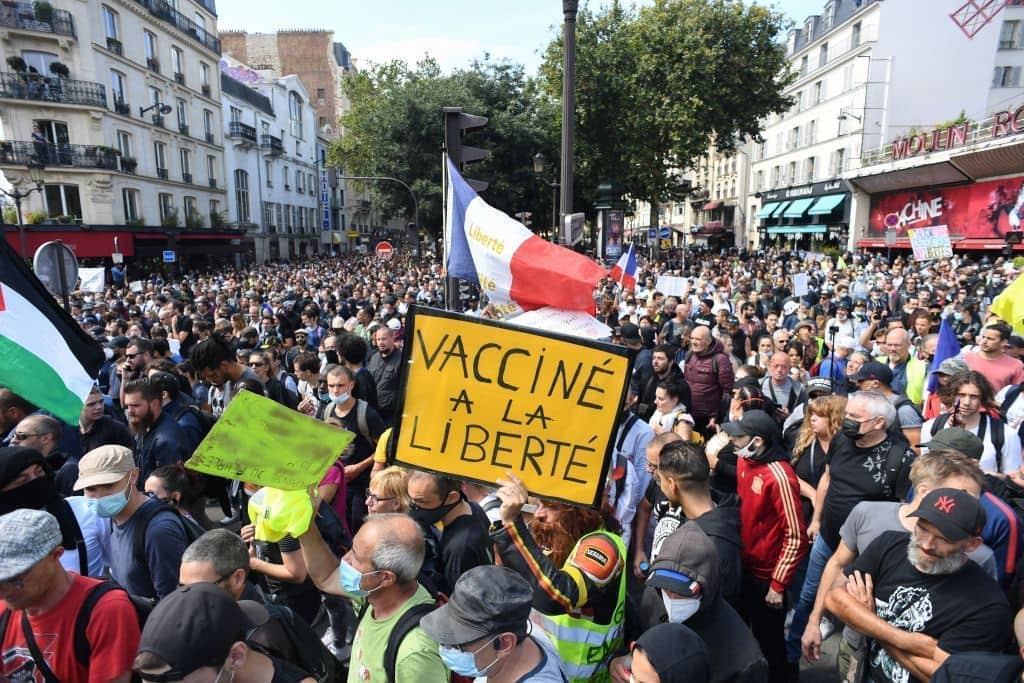

There is a minority of hardy French souls who agree. The anti-Covid pass marches still take place every Saturday and I would estimate that in Paris around one in five people flout the law that decrees masks must be worn outside at all times. That was before a judge in Paris last week repealed the mandate mask for outdoors because it was excessive, although the law has since been reinstated, partially, at bus stops and in queues. Nonetheless the majority of French continue to wear a mask outside, but why?

There are, at least, signs that things are changing. The French print and broadcast media, which is heavily subsidised by the state, lest one forget, have been enthusiastic in propagating the government’s doom-mongering throughout the pandemic. Only the broadcaster Sudradio, has dared challenge the narrative, along with the occasional op-ed in Le Figaro, such as the one today in which an academic likens the vaccine pass to China’s system of social credit.

In recent days, the media has been issuing encouraging noises to the effect that life could return to normal by the spring. Professor Alain Fischer, who sits on the French government’s equivalent of Sage, made that prediction in an interview, as did Albert Bourla, the head of Pfizer:

‘We’re going to soon be able to return to a normal life,’ he said on Monday. ‘We’re well placed to achieve that by the spring.’

Wouldn’t it be fortuitous if Macron was able to address the nation on the eve of voting in April’s French election and declare that he has won his ‘war’ on Covid? No more masks and no more vaccine passports. All thanks to the man who was nicknamed Jupiter when he became president in 2017. Jupiter, of course, was the God of Thunder, but as far as his ‘war’ on Covid goes, Macron has proved the God of Blunder. He spread misinformation about the AstraZeneca vaccine and reneged on a promise not to introduce vaccine passports. His government has made repeated mistakes in its Covid policy, some of which sparked a widespread strike by schoolteachers last week.

With energy prices rising and inflation soaring, Macron’s grandiose vision for France set out when he won office has not come to pass. Earlier this month, the president famously declared it was his intention to ’emmerder’ those who aren’t vaccinated. He’s done that all right, but the president has also peeved off millions of vaccinated Frenchmen and women who look around them at a France that is more violent, more divided and more despondent than at any time this century. Worse, the government’s muddled Covid strategy has turned the country into an international laughing stock: ‘Absurdistan’, as it was dubbed by a German reporter. Only the joke isn’t funny for those forced to live in Macron’s France.

Comments