In the early 1970s my father moved offices and I was plucked out of my cosy prep school in Surrey to land in the eccentric surroundings of Presentation College. My new school’s modern block was surrounded by decaying Edwardian villas occupied by Irish teaching brothers with impenetrable accents. There was a broken aeroplane on one of the lawns; I never found out how it got there.

Talk about a culture shock. Already I was besotted with classical music; to say that the brothers didn’t share my enthusiasm is putting it mildly. There wasn’t a flicker of interest in eight years – something that puzzled me until I read Thomas Day’s book Why Catholics Can’t Sing, which argues that, in the Irish diaspora, highbrow music stirs folk memories of English colonial occupation.

Presentation College didn’t even have a full-time music teacher. My parents soon decided I’d be better off at a public school that did. They were surprised when I refused to move. The reason? I was receiving an unofficial but first-class musical education from a young Anglican English master, Philip Fryer, who sang tenor in the finest choirs in the country.

Born to a tea-planting family in Ceylon, Mr Fryer spoke RP with the extra polish of an expat. He was handsome with a toothy smile and magnificent wavy hair. (‘Ooh, he’s dishy,’ sighed my statuesque piano teacher Mrs Oats after seeing him play a Gilbert and Sullivan romantic lead.) He loved his oddball colleagues – but he was a naughty mimic and couldn’t resist sending them up in stage Irish. I’ll never forget his imitation of an off-key Catholic congregation sliding into a rallentando at the end of every verse. He also did a mean Bob Dylan.

Mr Fryer, who went from ‘sir’ to ‘Philip’ when I was in the sixth form, could instantly spot a pupil who loved classical music – actually not difficult, since we were busy getting our shins kicked. He was also an expert sailor who introduced many boys to the sport but wisely didn’t rope me in. There was another musical nerd in my class, a shy lad called Michael Smith. Mr Fryer would drive us up to concerts in London and test our knowledge with a game he called ‘Spot That Tune’. ‘Give me ‘Morning’ from Peer Gynt,’ he’d say. That was easy, so he’d up the stakes to Beethoven’s Violin Concerto (I got that) or the beginning of Janacek’s Sinfonietta (Smith beat me to it).

Then there was a new excitement. Philip became a founder member of the Chorus of the Academy of St Martin’s in the Fields and in 1979 he took Michael and me to hear the ASMF (disguised for copyright reasons as the London Chamber Choir and Argo Chamber Orchestra), conducted by Laszlo Heltay, recording Haydn’s Stabat Mater in the gorgeous acoustic of St Jude-on-the-Hill in Hampstead. There was a luxury line-up of soloists: Arleen Augér, Alfreda Hodgson, Anthony Rolfe-Johnson (Philip’s singing tutor) and Gwynne Howell.

Philip always tried to pinpoint the moment in a work that, in its beauty, would eclipse everything else. His suggestions were inspired – for example, a long-delayed entry of the tenors in the first Kyrie of Bach’s B minor Mass. And if you doubt that the Haydn Stabat Mater is a masterpiece, listen to the chorus ‘Quis est homo’, which starts in declamatory fashion and then dissolves into a soft yet soaring fugue at the words ‘in tanto supplicio’.

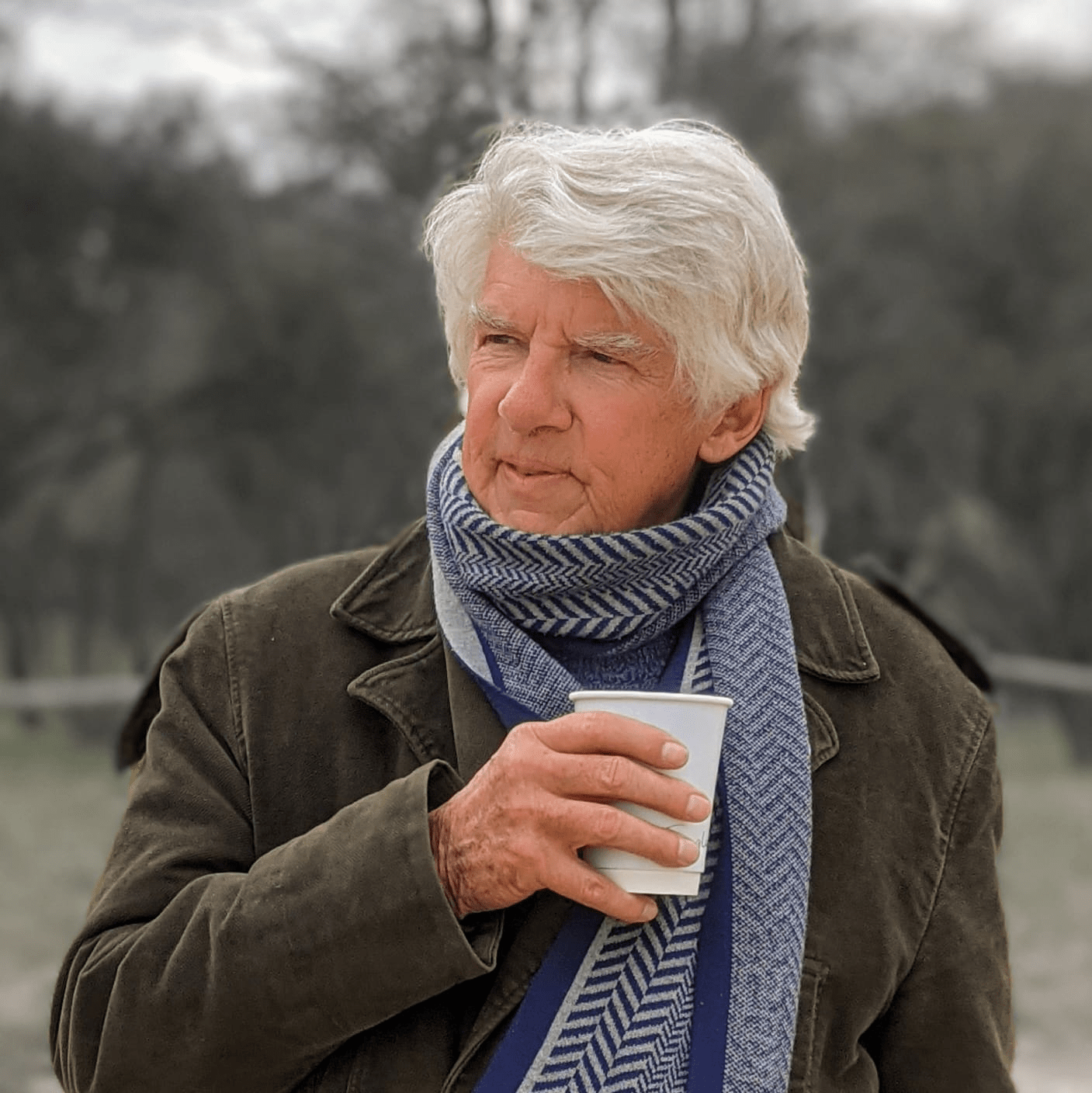

A few weeks ago, Philip, Michael and I sang those words together – joyfully but with a catch in our throats. Our beloved mentor was in a hospital bed on the Isle of Wight, suffering from a devastating lung disease. He was emaciated but still handsome; his daughter Ali, who is as charismatic as her dad, was doing her best to control the flow of lady visitors. There was often an over-supply of sopranos in the amateur choirs that Philip coached. He told Ali recently that conducting the island’s Gateway Singers, some of whom were discovering choral singing in their seventies, was the richest musical experience of his life.

Michael and I had planned to stay at the hospital for less than an hour, but Philip didn’t want to let us go. He was bursting with anecdotes, one of which involved a supposedly well-loved English conductor whose nitpicking during an Albert Hall rehearsal was so annoying that when Philip nipped out for a pee in the backstage gents he found the words ‘[well-loved conductor] is a cunt’ scrawled on the mirror. Looking back, I don’t think Philip would have told that story if he hadn’t sensed that we’d reached the end of our 52-year journey together. Knowing that when it came to musical gossip we were still schoolboys, he was determined that an otherwise sombre drive back to London would be punctuated with giggles.

Comments