Among the myths of Ancient Greece the Cyclops has become forever famous, the Talos not so much. While both were monsters who hurled giant boulders at Mediterranean shipping, the Cyclops, who attacked Odysseus on his way home from Troy was a monster like us, the son of a god, an eater, a drinker, a sub-human with feelings. The Talos was more alien, by some accounts a mere machine, manufactured in metal by a god and pre-programmed only to sink ships and roast invaders alive, a cross between a Cruise missile launcher and an automatic oven.

Talos began its existence just as early as the Cyclops. But it was only described with drama in the epic poem the Argonautica, by Apollonius of Rhodes some 500 years later. Homer’s readers have always been the more numerous. Only a few fans now read how Jason’s Argonauts overcame Talos with the help of the princess Medea, using thought-rays and her knowledge of Talos’s one weak mechanical spot.

In Gods and Robots, Adrienne Mayor, an American historian best known for her work on Amazons, aims to rescue the neglected automata of antiquity from the fleshy allure of goddesses and nymphs. For anyone probing the history of biotechnology and artificial intelligence, she suggests that Talos, defender of Crete for the famed King Minos, should be the star of Chapter One.

Mythic Crete is for Mayor a Silicon Valley of the very ancient world, home of the cryptic maze, the first manned flight (of Daedalus and doomed Icarus, his son), the first self-guided arrows. She selects the most bronze of the Bronze Age, from Talos clanking around the Cretan coast to the mindless robot army which, again with the help of Medea, Jason had to overcome to win the Golden Fleece.

This is an excellent source book for confronting political and technological hubris then and now, the earliest arguable traces of modern fears. Minos, she notes, was a peculiarly brutal autocrat, belonging to a class of men that she claims is especially associated with biotechnology and its abuse. He did not trust his queen, the witch Pasiphae, who made him ejaculate scorpions and snakes if he advanced on another woman. Pasiphae herself preferred sex with a bull, and engaged Cretan high-tech to provide a cow-shaped cage in which to crouch on her hands and knees, plus the farmyard smells for romantic atmosphere and the obstetrics necessary for the birth of a Minotaur.

Mayor’s second big robot star is Pandora, the mechanical vehicle by which Zeus brought humanity all its sorrows, packed up in a pot which, by mistranslation, came later to be known as a box. Pandora is not a woman but a cunningly constructed trap which has ‘no parents, no childhood, no past, no memories, no emotional depth and no self-identity or soul’. This product of the Mount Olympus automaton industry is like Homer’s self-opening gates for the gods’ chariots and the golden tripods which travelled from table to table delivering divine drinks. Automatic control can become no control at all.

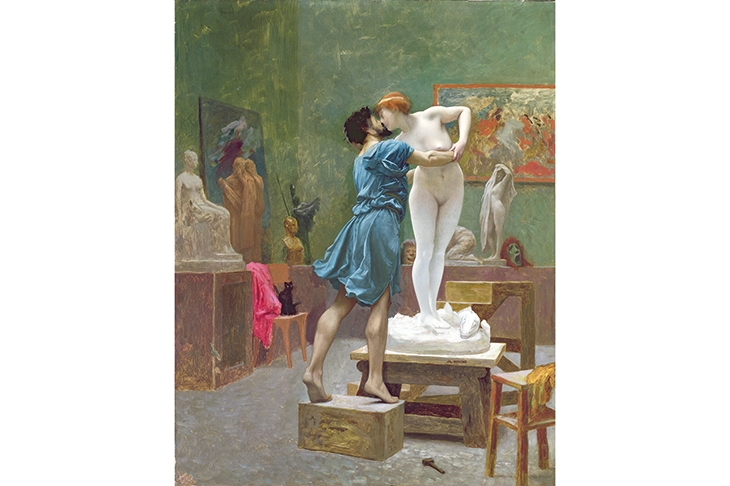

Mayor links the past and present of genetic manipulation, comparing Medea’s rejuvenation of an old ram by blood transfusion with the cloning of Dolly the Sheep. She notes how Pygmalion’s statue, Galatea, poses issues about dolls sold for sex. For every hope there was and is a fear. In some versions of the Pandora story Hope is a character in itself, the one gift of the gods which did not escape from Zeus’s pot.

This is much disputed territory. Did the Greeks have hopes and fears of technology before they had the technology itself? Many think not. Mayor thinks otherwise. Some sections of her book are vigorous seminar arguments with classicists and historians of science. Others make a dazzling stream of less connected subjects, allowing her to describe not only evidence of religious belief but automata that were amazing theatrical techniques, not just Pandora but the pecking eagles and libation-pouring statues that entertained the crowds when Apollonius was in Alexandria.

Did these machines inspire the poets or did the poets open the minds of the inventors? The very novelty of mechanical men and birds may have encouraged poets to interpret myths as technological when they could. Talos itself became more mechanical as time moved on. The details of the oil-tube between its neck and ankle and the vulnerable bronze plug that keeps the machine at work comes from 500 years after the writing of the Argonautica.

Could a mechanical android ever have a moral sense? Can it have one now? Where is the line? When Edmund Spenser wanted to introduce such questions in The Faerie Queene he created his own unbending, iron-man instrument of justice and called it Talus.

Comments