‘So f-ing Croydon,’ was the worst insult David Bowie could think of to describe a person or thing that revolted him. ‘Less of a place, more of a punchline,’ was a recent swipe by Sue Perkins, the Croydon-born comedian who grew up at the tail end of the town’s golden era of rampant employment, ambitious cultural venues and well-endowed private schools.

London’s outermost, southernmost, most populous borough is an easy target for condescension: too brash, yet too poor; too try-hard, yet too lethargic; too ambitious, yet not ambitious enough. As the Croydonian author John Grindrod has written, locals are accustomed to Croydon’s ‘very existence – our existence – provoking outrage’. Croydon, neither London nor suburb, can’t win.

If you pour scorn on Croydon,Will Noble argues, you pour scorn on yourself

In this gutsy, charming book, Will Noble asks us to think again. He suggests that the national contempt for Croydon as a ‘philistine, materialistic wasteland – a godless place’ is deflected self-loathing, bound up in anxiety about social class. In truth, Noble argues, Croydon is Britain in microcosm, with ‘its diversity of denizens, its mixture of urban grittiness and rural beauty, its antipodal wealth and poverty, its amassing cultural fecundity’. If you pour scorn on Croydon, you pour scorn on yourself.

Noble, who edits the cheerful Londonist website, looks beyond Croydon’s sprawl, grit and traffic and seeks to reframe the borough as a national marvel, the embodiment of brio. That is a lot to ask of readers whose only encounter with it has been as a foil, rattling over the dusty A232 flyover towards Gatwick and on to somewhere – anywhere – else. But Noble is undeterred.

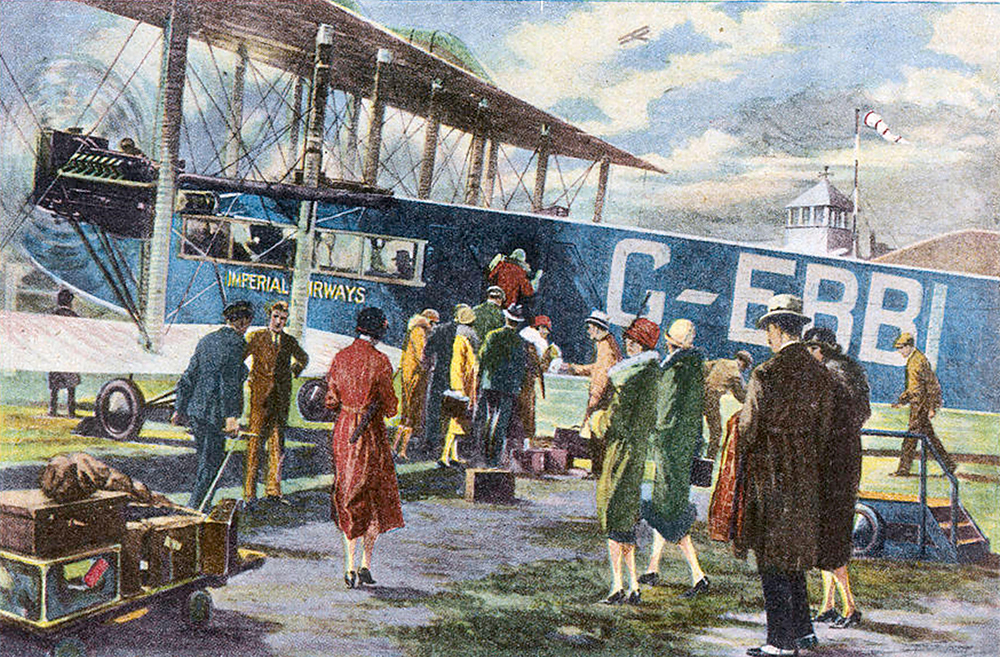

He starts from the town’s earliest history, with various archbishops of Canterbury who settled there from the ninth century (six are buried in Croydon Minster), and ends in the present era of Brit School stardust and municipal bankruptcy. He makes a case for Croydon as a place of firsts. The aerodrome, which opened in 1920, was eight years later the biggest, busiest airport in the world, serving leisure passengers at the end of the colonial era. It’s intact; you can still visit today and I recommend you do – it’s an art-deco wonder. The birth of the international air travel industry was crude (pilots worked out where they were by dipping down over railway stations to read the name boards), but Croydon was its cradle. The UK’s first black international superstar (the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor), the earliest supermarkets, affordable cars, punk records: they all came from Croydon.

It amounts to a town hungry for new ideas, sometimes to its own detriment. Special attention is paid to Sir James Marshall, Croydon’s post-war mayor with a mania for demolition and rebuilding in the brutalist style, and ‘such a redoubtable figure it’s a wonder he wasn’t made from reinforced concrete’. In 2020, Croydon was the first of a wave of councils to declare bankruptcy, largely due to poor leadership decisions and a flawed house-building scheme.

History and lost glory are fascinating, but lots of places are unloved and most could point to innovations. Why is Noble writing about Croydon – and why now? I think the answer lies partly in the housing crisis. In 2020, the Financial Times commissioned research from Zoopla, the property website, to find out where Londoners were searching for property in the first ten weeks of lockdown. Remarkably, Croydon was top – a reflection, perhaps, of a pandemic-era longing for space at reasonable prices within reach of the centre of London. Average property prices in Croydon are just over £400,000, compared with £721,000 in Hackney; the fast train takes 16 minutes to reach Victoria.

Noble writes that he moved to Croydon in 2022. Younger Londoners such as him rely on the borough as an affordable way to live in the capital. As ever with Croydon, the evidence is material. Chic new high-rise apartments have appeared, with abstract names such as Ten Degrees, and rooftop bars with views over the South Downs. Perhaps the town’s new, upwardly mobile residents crave pride, a sense of history and different ways of thinking about their home to cement its extraordinariness.

Despite its charm, Noble’s prose can sometimes register as a little too eager to convince. He scampers through Croydon’s recent problems as if they interest him less: political upheavals after the council declared itself bankrupt; poverty, the roots of the 2011 riots.

Croydon is home to Lunar House, the front line of the Home Office’s immigration services, where new arrivals to the UK have reported for processing since 1970. Noble writes about the building, but the extraordinary range of people who stayed where they landed and their descendants who make up modern Croydon’s population are scarcely mentioned. There is no escaping the borough’s sclerotic public services and its failures of vulnerable people, nor the rundown look and feel of much of it.

Still, Noble exposes Bowie’s instinctive contempt as misplaced and deeply ironic. For all its debt, deprivation and concrete, at its best Croydon was a dynamic, heroic place. In many ways it remains so. It is more interesting than boring old Beckenham, where the master of reinvention and the avant-garde chose to live until he left for the US in 1974. We need Croydon’s brio, its spirit of futurism, more than ever.

Comments