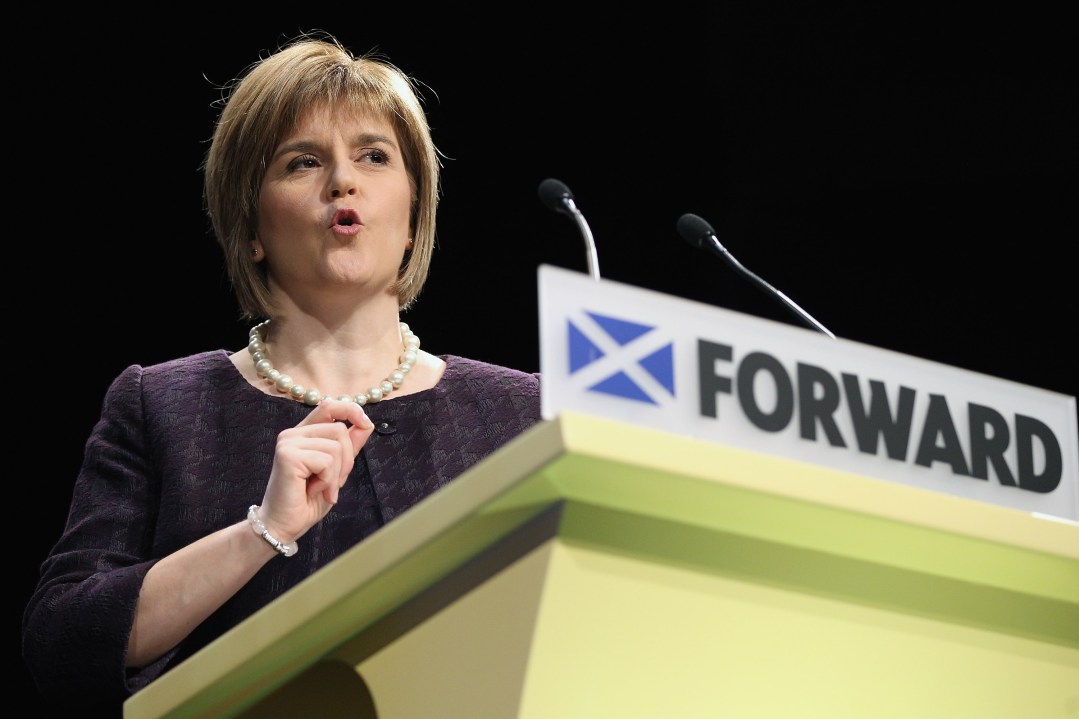

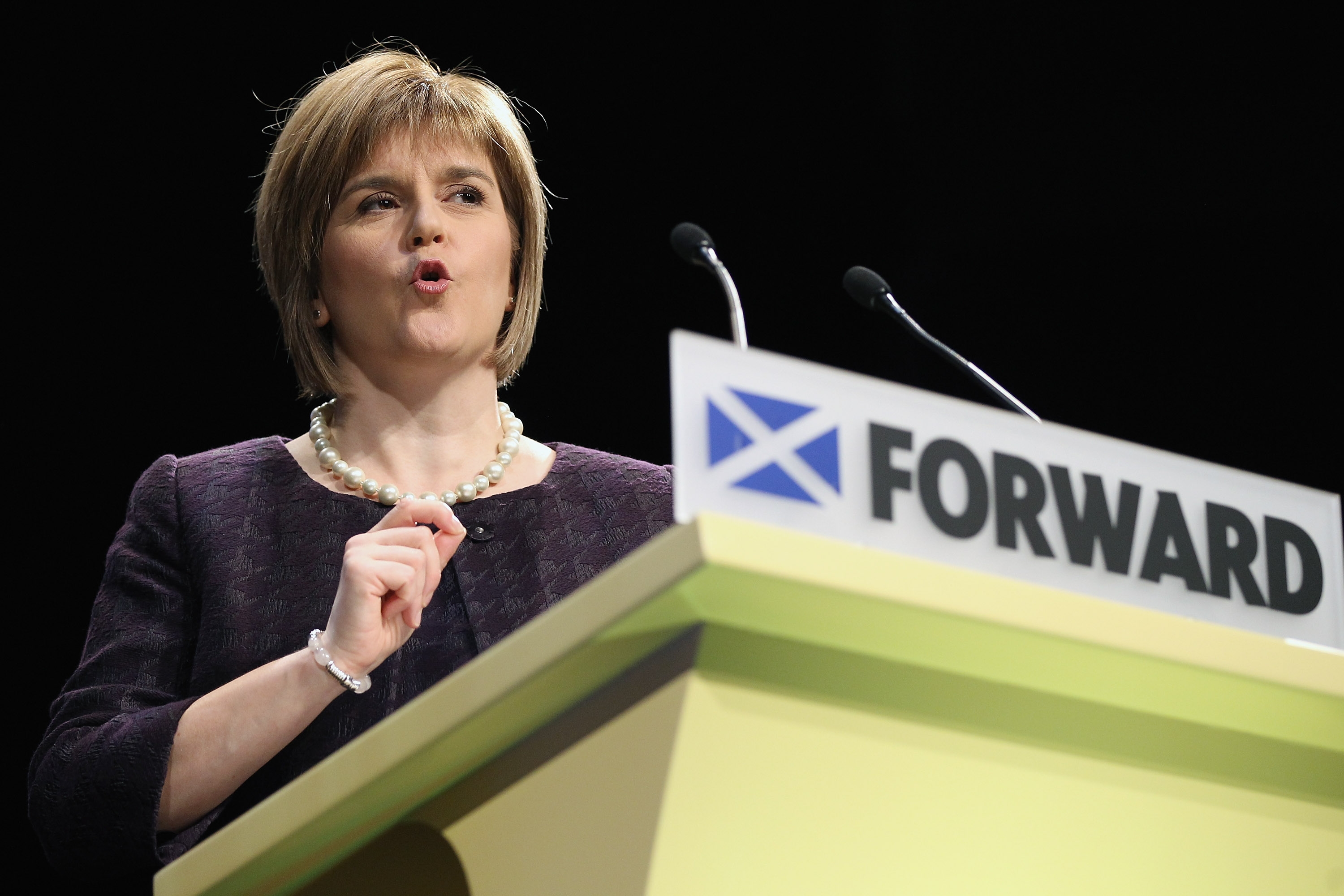

In the rabid hamster-eating-hamster world of Scottish politics Nicola Sturgeon is a rarity: a politician of obvious competence who’s respected by her peers regardless of their own political allegiances. There are not so many folk at Holyrood of whom that could be said. The Deputy First Minister is not a flashy politician but she’s quietly become almost as important to the SNP as Alex Salmond. This, according to one sagacious owl, makes her one of the ten most interesting politicians in Britain. Hard though it is to imagine this, there are voters immune to the First Minister’s charms. Part of Nicola’s remit is to reach those parts of Scotland that are disgracefully reluctant to trust Mr Salmond.

So Unionists should take Sturgeon seriously. Yesterday she gave her first “major” speech since she assumed responsibility for the constitutional question. The Guardian’s Severin Carrell has written a fine analysis of it and Sturgeon’s speech is also the subject of my latest Think Scotland column:

She began with a fine line from TS Eliot: “We shall not cease from exploration and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time”. Of course, that could be the case if Scotland votes against independence too but, nevertheless, it’s a good line.

Similarly, the Deputy First Minister talked about “bringing the powers home to build a better nation”. This, like her defence of Holyrood’s history was a matter of presenting the independence debate not as a stark choice between two choices but, rather, as the natural progression of choices made in the past. You need some memory these days to recall the time when the SNP opposed devolution, placing its faith in a Single Heave theory of constitutional change.

Noting the distinction Neil MacCormick drew between “existential” and “utilitarian” nationalists, Sturgeon suggested most SNP supporters are part-existential and part-utilitarian. That is, happily, even conveniently, Scotland should be independent because Scotland is a nation and an independent Scotland would be better than a non-independent Scotland.

Almost no-one disagrees that Scotland is a nation. Almost every Unionist in Scotland is also, at times, some measure of nationalist. This is something SNP supporters too often overlook. But from Sir Walter Scott to Donald Dewar, there’s a thick streak of nationalism running through Unionism. If there weren’t it is hard to imagine how Scotland could have survived – in thought and deed alike – as a distinct nation. That survival, in fact, may be one of this country’s signal achievements these past 300 years.

More contentiously, perhaps, the Deputy First Minister went on: “I don’t agree at all that feeling British – with all of the shared social, family and cultural heritage that makes up such an identity – is in any way inconsistent with a pragmatic, utilitarian support for political independence.” Since I have often argued that Scots would retain a considerable British inheritance even after independence, I have some sympathy for Sturgeon’s view. Nevertheless, the “Britons for Independence” party has a pretty tiny membership, no matter how many SNP figures try to persuade you otherwise.

There is a slipperiness at work here, however. Many Scots, comfortable with their dual identities, do feel independence would threaten the British element of their identity. Consider the Irish. They too – as Nicola Sturgeon noted – have many strong and enduring ties to the constituent parts of the United Kingdom. They also enjoy a considerable cultural inheritance that can reasonably and simply be considered “British”. This exists even if it is also often denied.

Nevertheless, the Irish are not British in quite the same way or to the extent Scots are or would be after independence. We might still be more British than the Irish but we would, unavoidably I think, be less British than we are at present. For some people this will be a loss and while the depth of that loss may be questioned its reality should not be denied.

Actually, despite outing herself as a utilitarian nationalist, Sturgeon reveals that she is in fact also an existential nationalist. “My conviction that Scotland should be independent stems from the principles, not of identity or nationality, but of democracy and social justice.… I joined the SNP because it was obvious to me then – as it still is today – that you cannot guarantee social justice unless you are in control of the delivery.”

Of course, one could make the same argument about local government. Yet here the SNP shows no interest in devolving power to the smaller battalions. I say this not with any spirit of rancour, merely with a half-raised eyebrow.

Be that as it may, I would also quibble with another part of Stugeon’s argument. She argued that Britain has under-performed and that this means Scotland has too. Or, as she put it:

“Over the past 50 years, Scotland’s average economic growth rate has been 40% lower than equivalent, independent countries.

Recently, the Economist Intelligence Unit published its ‘where to be born’ index that looks at a range of quality of life measures. The UK ranked 27th. But four out of the top five countries – Switzerland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark – are countries with many similarities to Scotland.

What do these other small countries have that we don’t? It’s not resources, talent or the determination of our people. What they do have is the independence to take decisions that are right for them. The example of these other countries should tell us that the challenges we face today are not inevitable. The problems can be solved – but only if we equip ourselves with the powers we need to solve them.”

Again, there is some truth to this even if rapid economic growth is frequently really evidence that you’re starting from a low base. The US economy will not grow as fast as, say, El Salvador’s. Moreover, in some very important ways Scotland is not at all like Switzerland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Indeed, beyond being comparably-sized countries I’m not sure Scotland has very much in common with any of them. We certainly do not share their commitment to local democracy or mixed private-public provision of government-sponsored services.

Most importantly of all, none of these countries were at the forefront of the industrial revolution. Nor, it follows, were they stuck with the legacy of decline common to many of the regions around the world once most-heavily dominated by heavy industry. In many important respects greater Glasgow is much more like Cleveland than it is comparable to Copenhagen. (The reverse is true of Edinburgh or Aberdeen.)

Most of the grievous problems Scotland faces are related to this sorry fact. From health to education to employment, community cohesion, dignity and much else besides it always comes back to the grim truth we have not managed to revitalise the west of Scotland. The rest of the country is doing fine; large parts of the west are being left behind. The divide between Edinburgh or Aberdeen and parts of Lanarkshire or Renfrewshire is comparable in kind to that between London and Tyneside.

There is a plausible argument that the Union will not alleviate these problems. It does not follow axiomatically that independence would. It’s not impossible that it could help but, looking at the ideas that find favour with the Scottish Consensus I’m not sure I’d wish to wager too much cash on that proposition. I would add that the woes of Tyneside, Wearside, Teesside and Merseyside are evidence that Westminster may have failed these places but since their rustbelt woes are much the same as Glasgow’s it is not necessarily obvious that Glasgow’s problems are either peculiarly Scottish or peculiarly susceptible to Scottish solutions. Again, it is nice to think they must be; it is not evident that they actually are.

There is an irony too in that the SNP have decided to appeal to Labour-voting or Labour-sympathising voters in the west of Scotland by decrying the failure of past Labour government’s to improve their lot even as the SNP’s actual policies are frequently hard to distinguish from the past Labour policies that the SNP argues have done little to improve life in the parts of Scotland that most need that improvement.

Independence, according to Sturgeon, offers “A chance to begin again in response to the 21st century.” Perhaps it might. She added, “There is little point in bringing the powers home to just carry on as before” and, again, this might be true. But that too makes it odd that the SNP’s actual policies are, broadly speaking, rooted in a view of Scotland, its needs and its society, that is largely unchanged in at least 20 years.

Whole thing here.

Comments