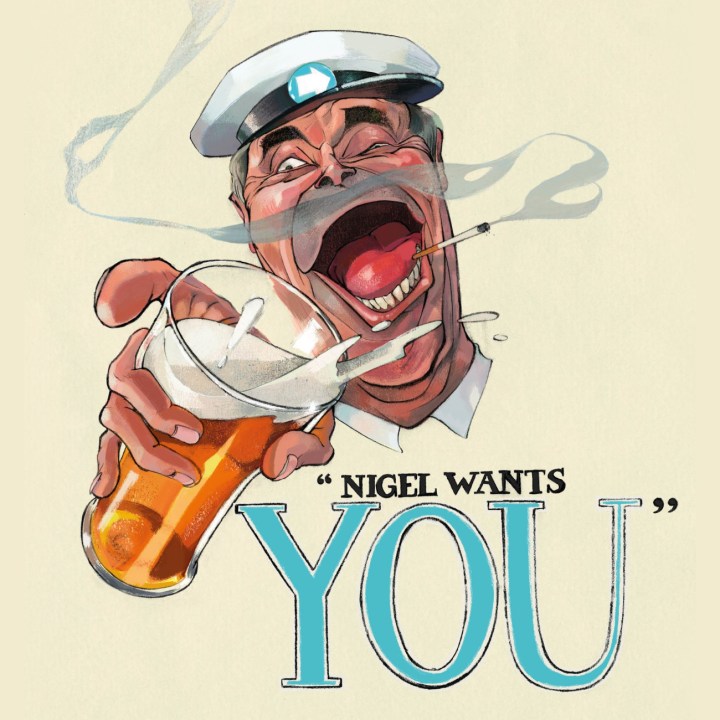

‘I’ve changed my mind!’ It is a year this week since Nigel Farage uttered those fateful words, marking his decision to return as leader of Reform UK during the general election campaign. Much has changed in those 12 months. The party’s polling has doubled, membership has soared to 235,000 and new faces make up most of the backroom staff.

Now that the party has hit 30 per cent in the polls, Reform strategists insist the vote share can go higher: 40 per cent is viewed as a realistic target. Zia Yusuf, the party chairman, likes to describe Reform as a ‘start-up’, breaking apart SW1’s monopolistic cartel. This high-ambition, high-growth strategy yielded 677 councillors in the local elections last month.

But, as with any new firm in a competitive market, the challenge is how to scale up at speed. More than 3,000 candidates must be found by next May, owing to a bumper set of elections across the country. In London alone, there will be 1,800 council seats up for grabs. ‘The vetting will be a nightmare,’ groans one aide. Most attention will be on Scotland and Wales, where the different electoral systems will influence decisions on candidate announcements. Cardiff Bay’s new voting system, which is not constituency-based, means organisers see little benefit in publishing names until next year.

Such work is happening alongside planning for the general election in 2029. The British system has traditionally prized party loyalty and slow, steady advancement through the ranks. MPs attempt to climb the greasy pole; cabinet ministers emerge after many years in parliament. A Farage victory would, by necessity, make a break with all that. Assuming that Reform does not merge with the Tory party, almost none of Farage’s MPs would have any experience as ministers. This would be a government of novices, the likes of which Whitehall has not seen since Ramsay MacDonald in 1924.

Reform strategists insist they want to get genuine expertise into office. Farage has long had an appreciation of the American system. In the US, the President has much greater flexibility in compiling a cabinet, whose members do not have to sit in Congress. British ministers, however, are bound to answer to parliament. Such a constraint could be navigated via the House of Lords. Gordon Brown gave the likes of Digby Jones and Alan West peerages and posts in his short-lived experiment to produce a ‘government of all the talents’. Senior Reform figures favourably cite the speed at which Rishi Sunak elevated David Cameron to the Upper Chamber in order to make him foreign secretary. Should Farage win an election, he would be entitled to do the same for his appointments. He says he is committed to the abolition of the Lords – yet there is an expedient case for a temporary stay of execution.

The Brexit party showed how a strong cause can produce an effective list of candidates

Inspiration is to be found elsewhere abroad too. One precedent from Italy is the populist party Five Star Movement, which in 2018 struck a power-sharing pact with the right-wing Lega Nord. During that election, Five Star listed its likely cabinet choices to the electorate, making clear which names would join the new government if they won. Almost none had experience of ministerial office. Farage could similarly unveil a potential cabinet in the middle of a general election campaign. A general could go to defence; a doctor to run the NHS.

The Brexit party, Reform’s previous incarnation, showed how a strong cause can produce an effective list of candidates. Party old-timers fondly recall how its 2019 European election line-up was socially and politically diverse. On the left there was Claire Fox, a former revolutionary communist, and on the right Ann Widdecombe, a true-blue Tory grandee. Others included the salmon trader Lance Forman, Malaysian-born nurse Christina Jordan and businessman John Longworth. A democratic imperative bound these characters together as candidates in 2019. The same sense of purpose will be required if Reform is to run a similar slate ten years on.

Various groups in the party will produce candidates for 2029. Some of those 677 councillors elected for Reform last month will stand for a seat in the Commons, having proven their worth in local government. Yusuf likens this to Barcelona FC’s La Masia youth academy: a production line of talent who know the identity of the club and how it likes to play.

Various criteria are used to assess turncoats, including their expertise and propensity to cause trouble

Council leaders such as Linden Kemkaran in Kent and Sean Matthews in Lincolnshire could make the jump to national politics in 2029. Essex is something of a hotbed: branch chairs Sophie Preston-Hall and Tom Allison are often cited as rising stars. Jaymey McIvor is now the party’s director of local government and Natalie Oliver in Lincolnshire is also regarded by Reform’s leadership as a future ‘rockstar MP’. Rather than create a national youth wing – with all the inevitable baggage – Reform is happy to let teenagers and twentysomethings stand and cut their teeth on councils.

There will be a considerable push to attract influential business figures as well. High-profile contacts from the worlds of tech and finance will be approached, courted and assured of Reform’s intent. ‘We want genuinely impressive people,’ says one senior source. ‘Unlike the muppets you have had in recent cabinets.’ Sporting figures – with their perceived ‘get up and go’ attitude – are wanted too. Reform is aiming to replicate the success of Luke Campbell, the Olympic boxing gold medallist turned mayor of Hull. Derek Chisora, another boxer and a longtime Farage fan, is also reportedly keen to stand. There is the hope of attracting a rugby star for Cardiff Bay next spring. ‘We get a lot of cricketers interested,’ remarks one insider.

Then there are the media personalities. Last month the former GB News presenter Darren Grimes made the jump from broadcasting to politics, becoming Durham County Council’s deputy leader. Others will probably follow him. Various veterans of Farage’s former outfits appear alongside him on GB News, including Michelle Dewberry, onetime winner of The Apprentice, and Martin Daubney, a former editor of Loaded magazine. Both stood as candidates for the Brexit party in 2019. Other 2029 candidates could include the pollster Matt Goodwin, who has been touring Reform’s branches, and TalkTV’s David Bull, who compèred Reform’s big Birmingham rally in March.

Finally, there is the thorny subject of defectors. Reform presents itself as new, fresh and exciting: an explicit rejection of the old two parties. How then should it regard Tory MPs looking to defect? Talk of a ‘defection clock’ – a date by which any newcomers would have to join – has been discussed but ruled out for now. Various criteria are used to assess turncoats, including their expertise, skill set and propensity to cause trouble. ‘What’s their expectation?’ is perhaps the key question asked of any would-be defector. Some, such as the new Reform MP Sarah Pochin, formerly a Conservative councillor, are regarded as true believers. Others are dismissed as being simply after a job.

Certainly, Reform is not short of offers. On Monday, Farage announced two new Scottish councillors, one joining from the Tories, the other from Labour. Senior figures in Reform are keen to emphasise the points of agreement in the party’s ever-growing electoral coalition. Much like the traditional Tuesday cabinet meeting, Reform’s five MPs have a weekly call to discuss strategy. Points of contention are brushed over, in favour of common ground such as abolishing net zero, scrapping Diversity, Equity and Inclusion schemes and leaving the European Convention on Human Rights.

The next 12 months are seen as an opportunity for experimentation, while Labour flounders and the Tories battle for relevance. Senior figures are confident that neither Kemi Badenoch nor any would-be Tory successor poses much of a threat. ‘It’s institutional as much as personal,’ says one. ‘Their brand is dead.’ Another relishes talk of a Boris Johnson comeback, saying that Reform would blitz any by-election with reminders of Johnson’s record on migration. ‘We’d make the online offline,’ he says – in reference to the so-called ‘Boriswave’ of new migrant arrivals after 2021.

Farage’s skill at making the political weather ensures there is plenty of flexibility when it comes to announcing policy. ‘There is so much space up for grabs,’ remarks one aide. Reform’s plans to champion crypto-currencies is one example: men in their twenties are among the most active users of digital assets – and also the least likely people to vote. The party is happy to try new things. It is expected that Reform will soon make a pitch targeted at millennials enraged by Britain’s fraying social contract. Over the summer there will also be a steady drumbeat of stories about waste, fraud and incompetence in local government.

A year after his change of heart, Farage is halfway through his four-stage plan. Step one: get elected to parliament. Step two: win the local elections. Step three: win Wales. Step four: become PM. As more voters join his self-described ‘People’s Army’, rivals desperately seek to stop him in his tracks. The Liberal Democrats, for their part, have started to describe themselves as the ‘antidote’ to Reform. This week, strategists met to discuss next steps on ‘ReformWatch’, their bid to hold Farage’s councillors to account.

‘You all laughed at me,’ Farage once said: ‘Well, I have to say, you’re not laughing now, are you?’

Comments