Change. If one word can embody the political philosophy of Keir Starmer, it’s this one. The Prime Minister is ever so fond of it. Starmer deployed it copiously on his way to Number 10, and it’s been his repeated mantra ever since. No wonder that when the PM unveiled his big new idea this week, it was called The Plan For Change. He’s obsessed with the word and the concept. The problem is that much of the public aren’t so enamoured of change. Many people don’t like the way British society has changed. They would have preferred if things had remained as they were. Much of the public still want things to stay the same.

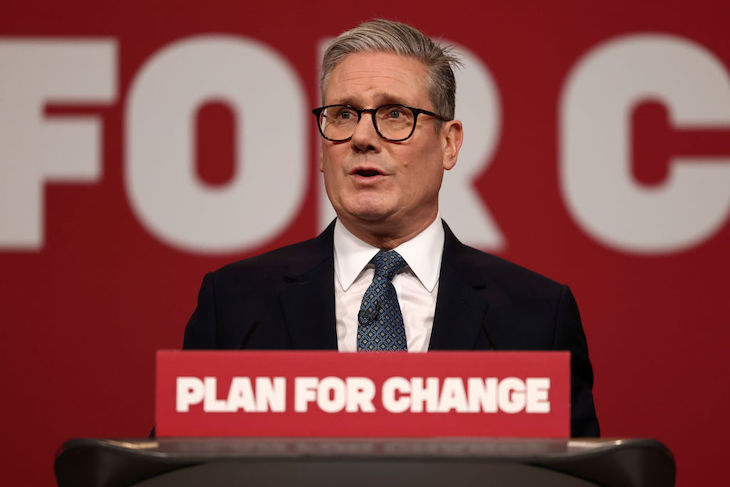

Starmer is obsessed with the word ‘change’

We aren’t just talking about the tangible change effected by the new Labour government since coming to power, most of which has been hugely unpopular: the hike in national insurance and implementation of wide-reaching and costly rights for workers, the cut to pensioners’ fuel allowance, new inheritance laws affecting farmers, the appeasement of the unions. Such change, in the minds of so many, has been change for the worse.

We’re not even just talking about change enacted for its own sake, where there has been no public demand for it. Plans to give away the Chagos Islands or the Elgin Marbles have met no public demand whatsoever. Initiatives to clamp down on people’s lifestyles and simple pleasures, from the government’s abortive attempt to ban smoking in pub gardens to its war on fast food, including, now, the ban on some TV adverts for porridge, reveal a government prone to mindless tinkering and meddling.

No, we’re also talking about the long-term change to British society that has caused so much discontent. This was the source of resentment that pushed many old Labour voters into Tory arms in 2019. This is the change many have witnessed to their towns, neighbourhoods and schools ever since Tony Blair opened the proverbial door to mass immigration in 2004, a process accelerated by Conservative governments ever since, despite their lip-service to the issue. The Red Wall demographic voted for Brexit, to take back control, not because they wanted ‘change’, but because they were fed up of it.

Conspicuous by its absence in Starmer’s five steps for change, on improving economic change, the NHS, the environment, societal opportunities and policies, is any tangible measure to address immigration levels. There will be no specific new migration target.

The government will be understandably hesitant in imposing one, given how failed targets have proved such a millstone for the Conservatives. The Labour party are most likely fearful of approaching the entire subject, given that immigration can be such a sensitive issue. But it’s at the centre of so many people’s concerns. It’s not just the numbers, and the impact on hospitals, schools, housing and infrastructure. It’s how immigration affects Britain’s culture and sense of who it is.

In this area of national culture, the neophilia of the Labour party, abetted by its progressive allies in universities, schools and museums, has been especially alienating. This love of the new has corresponded with a hatred of the old, particularly of Britain’s past. Many are not just fond of the Britain they remember in their lifetimes, but the Britain of our shared, collective memory. This is the British past that is now constantly traduced, slandered and misrepresented on account of its empire, racism, slavery and oppression.

In this regard, Starmerism chimes with a wider mood in the West that looks upon the past with contempt and disdain. As the sociologist Frank Furedi writes in his new book, The War on The Past, this hatred of the past has a corrosive influence on our the present: ‘It is difficult to develop a sturdy sense of collective identity without a shared memory.’

Starmer’s constant invocation of ‘change’ cannot be viewed in isolation when viewed backwards, either. It’s much in keeping with Tony Blair’s very deliberately entitled ‘New Labour’ mission. Back in the 1990s and 2000s we had a prime minister who conflated ‘now’ and the ‘future’ with the positive, and used ‘old’ as a synonym of ‘bad’. The rhetoric of our current prime minister underlines that tradition and inheritance.

Sure, people did want change of sorts back in July this year, just as they wanted something ‘new’ in 1997. But what they would prefer right now is not change, but reform. This is why, by accident or design, the name and mission of that new interloper political party seems increasingly to appeal to many of a socially conservative disposition: old Labour voters and actual Conservatives.

People want institutions mended, the system fixed. They don’t like change for its own sake. In these times of flux, instability and fear of what the future may hold, what many want now is stasis and stability.

Comments