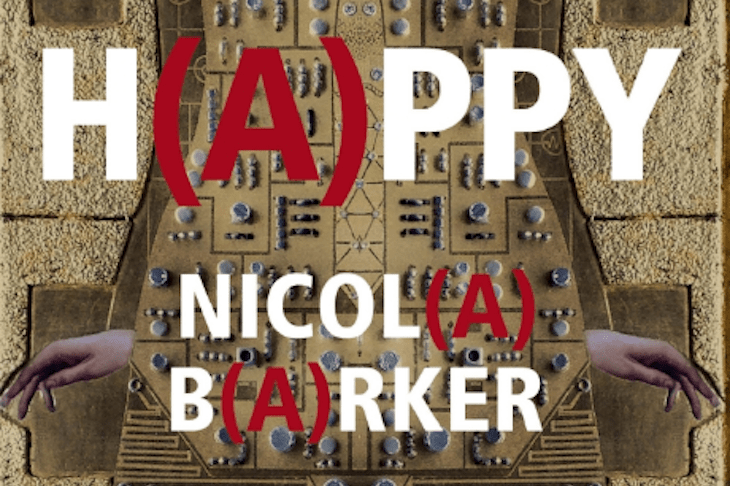

It is an unexpected pleasure when fiction has a soundtrack to accompany the work of reviewing. H(A)PPY is ‘best enjoyed in conjunction with Agustin Barrios: The Complete Historical Guitar Recordings’, Nicola Barker advises before her text gets underway.

It’s tempting to dismiss this as a gimmick. But Barrios’s music strikes a deep chord with the rebellion at the heart of Barker’s 12th novel. Born in the 1880s, the Paraguayan’s playing was ridiculed because he preferred his guitar strings to be made of steel rather than fashionable gut. His dissonant art, like Barker’s today, could not be accused of courting admiration.

The ‘sad-happiness’ of Barrios’s music is what comes to destabilise H(A)PPY’s ‘post-post apocalyptic world’. This dystopian tale of sorts begins simply: the ‘filth and degradation’ of life as we know it has been relegated to a sad corner of the earth, while the Innocents lead an almost flawless existence in accordance with the System. Bodily problems have been resolved: there is no pain, no ageing, no death. Everyone strives (not too hard) to exercise self-control and remain in the Moment. It is, I guess, like being conscripted to a never-endingmindfulness retreat, with the added injustice of other participants enjoying open access to your thoughts. The potentially therapeutic, when taken to the extreme, becomes a tyranny.

Barker does not tell us much about what this new world looks like, but we learn what it feels like. Mira A, a musician and maker of guitars, is struggling to stay ‘in Balance’. Her thoughts — like everyone else’s — are broadcast on the Graph, also known as the Sensor. This psychological FitBit, instead of calories, tracks emotional equanimity. The words of Barker’s text change colour as Mira A’s feelings inappropriately intensify, like the ‘pinkening and purpling’ Sensor which warns when an EOE (Excess of Emotion) is imminent.

Mira A cannot quite convince us she is HAPPY; rather, she’s ‘H(A)PPY’. The Innocents are concerned about this parenthesis. Could she be the ‘unsteady, tipping domino’? In the System, narrative itself is considered toxic. Fragments keep appearing on Mira A’s Stream which she cannot help but connect: a guitar waltz, an image of a young girl, a cathedral. Even after chemical intervention and a surgical operation, Mira A’s mind continues to resonate with an emerging story ‘like a metal guitar string’. Her Stream becomes flooded with text — about Paraguay, Barrios’s biography and incomprehensible snippets of history.

The novel’s later pages are graffitied with diverse fonts and erratic capitalisations in ‘a heaving, streaming, tropical rainforest of incomprehensible words words words words words words’. The shape of a guitar is bleached out from the printed text. Sections read like poems, appear like pictures, sound like music. Overwhelmed by the effort of self-policing, Mira A finally finds freedom in the human urge to ‘tell the story of myself. As if I am distanced from myself.’

I finished the book spent but impressed. It will be a while before I find the energy to reread H(A)PPY, but the delights of Barrios are effortlessly repeatable. ‘I can’t expect you to understand why this resonates with us so deeply,’ says a non-Innocent about Barrios’s art. In graceful tribute, Barker has written herself into this music, celebrating the beauty of its imperfection. She also plays uncompromisingly on steel strings — and creates something harsher and brisker than many novel-readers are used to — which aspires beyond being merely understood.

Barrios’s work today enjoys great popularity. Barker’s timely, invigorating novel risks becoming popular, too.

Comments