In May 2019, the first World of Bob Dylan conference was held in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Why Tulsa? Because Dylan’s archives are there, acquired in 2015 by the George Kaiser Foundation and the University of Tulsa for a reported $15-$20 million. Tulsa was already home to fine museums and important historical and archival collections. In a statement in 2016 Dylan said he was glad that his archives ‘are to be included with the works of Woody Guthrie, and especially alongside all the valuable artefacts from the Native American nations’.

First housed in the Helmerich Center for American Research, part of the Gilcrease Museum, the Bob Dylan Archive is soon to be moved to its own building, the Bob Dylan Center, built on the scarred ground in downtown Tulsa where in 1921 a massacre occurred. A brilliant essay in The World of Bob Dylan begins with the massacre, or what its author Greil Marcus refers to as ‘the white pogrom that destroyed the black community in Tulsa’. Marcus’s essay is on the blues, and its roots in African-American communities where ‘Tulsa sent the loudest message: anything you have, anything you are, can be taken away at any time,’ and concludes in a discussion of Dylan’s 1997 album Time Out of Mind.

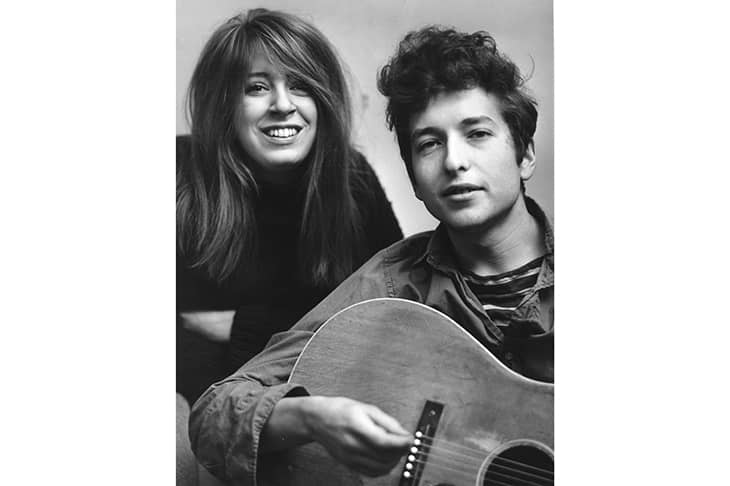

The World of Bob Dylan contains pieces initially given as papers at the eponymous conference, such as Marcus’s and the crackerjack, witty ‘Gender and Sexuality: Bob Dylan’s Body’ by Ann Powers. Her Tulsa audience erupted in laughter when she showed one of Ted Russell’s photographs of Dylan and Suze Rotolo in their Greenwich Village apartment in 1961 and commented: ‘At first glance, they look like an adorable lesbian couple.’ Other essays, such as Kim Ruehl’s knowledgeable ‘Roots Music: Born in a Basement’, were written for the book.

Few musical artists have ever been as adored and squabbled over by fans as Dylan is

The collection has five parts, or acts: Creative Life, Musical Contexts, Cultural Contexts, Political Contexts and Reception and Legacy. The section on musical contexts is, rightly, the longest, though how do you separate folk, country, rock, the American songbook and the vast and all-inclusive category called roots? You can’t, and especially not when you’re talking about Bob Dylan. He was, and is, as his old friend Liam Clancy once described him, a sponge, soaking up songs and types and forms of music, carrying all with him in his own art, leaving nothing on the side of the road.

Chapters cover Judaism and Christianity, the civil rights movement, theatre and its shaping of Dylan’s stage and film performances, literary influences and his longtime but relatively recently prominent visual arts. For Dylan the painter, Raphael Falco begins with a gem from the Bob Dylan Archive — a 2011 note from the singer Tony Bennett, himself a painter as well: ‘You are a wonderful painter. If Goya were alive he would kiss your hand.’

In writing of Dylan and the counterculture, Michael J. Kramer gives close readings of the manner in which Dylan registers concerns of the times from the Vietnam War to ‘racial injustice unsolved’ and ‘recasts them into a set of moody parables on [his 1967 album] John Wesley Harding’. Kevin Dettmar is keen and wickedly smart about Dylan’s long-noted quotation, echo, allusion, sharing, playgiarism (after Richard Federman), stollentelling (after James Joyce), or what-you-may-call-it in ‘Borrowing’.

It’s too soon for that fifth act, ‘Reception and Legacy’. Surely the Nobel Prize in Literature that Dylan was awarded in 2016 deserves a chapter, and James English supplies it. David Shumway’s ‘Stardom and Fandom’ reminds us that Dylan achieved the first early on, but that the latter has always been problematic. Fans of ‘folkie Dylan’ famously rebelled when he ‘went electric’ at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965, and condemned him as ‘Judas’ when he played searing sets with The Hawks — soon to be The Band — in 1966. Fans howled when he disappeared to Woodstock to live his life and raise his family, and when he became a born-again Christian. Few musical artists have ever been as passionately adored and squabbled over by fans as is Dylan: he attracts devotion and dangerous obsession. Stories in the press of the hundreds of millions he is now worth as a result of the sale of his music catalogue to Universal Music Publishing Group last year have brought admiration, envy and darker, stranger things out of the woodwork.

The world of Bob Dylan can’t really be put between the covers of a book. To paraphrase Dean Martin, it’s Bob’s world, we just live in it. Ellen Willis was right about Dylan more than half a century ago, and she is still right today:

Dylan is… shaped by personal and political nonconformity, by blues and modern poetry. He has imposed his commitment to individual freedom (and its obverse, isolation) on the hip passivity of pop culture, his literacy on an illiterate music. He has used the publicity machine to demonstrate his belief in privacy. His songs and public role are guides to survival in the world of the image, the cool and the high. And in coming to terms with that world, he has forced it to come to terms with him.

Comments