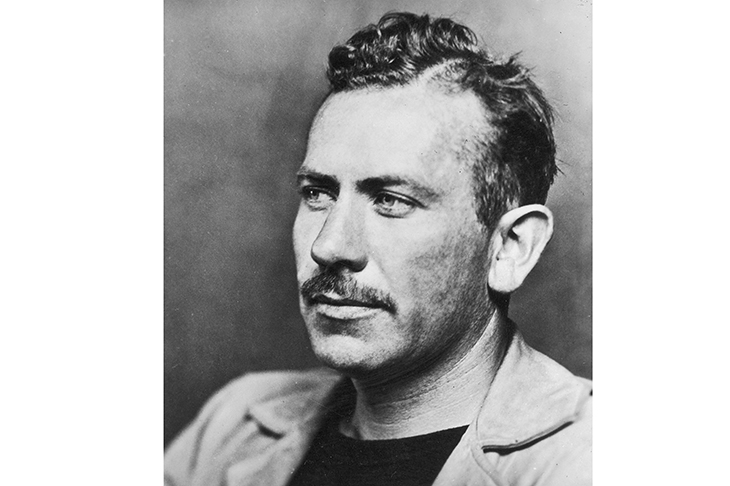

John Steinbeck didn’t believe in God — but he didn’t believe much in humanity either. When push came to shove, he saw people as cruel, selfish, dishonest, slovenly and, at their very best, outmatched by environmental forces. Like his friend, the biologist Ed Rickett, Steinbeck considered human beings to be no better and no worse than any community of organisms: they might aspire to do great things, but they always ultimately failed.

In The Grapes of Wrath, the hard-working Joad family travel west, seeking a good life, and get taken apart by poor wages, malignant farm cooperatives and company stores. In Cannery Row, Mack and his boys want to repay their friend Doc for all his generosity, and end up burning down his lab after a drunken party. And while the paisanos of Tortilla Flat see themselves as noble knight errants right out of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur (Steinbeck’s favourite book as a child), whenever it comes to a choice between doing good deeds and feeding their bellies — well, spoiler alert, their bellies always win.

Steinbeck never wrote about heroes and villains; he was more interested in the ways individuals were shaped by their environments and their communities. In order to create characters, he wrote in Cannery Row (1945):

You must let them ooze and crawl of their own will onto a knife and then lift them gently into your bottle of sea water. And perhaps that might be the way to write this book —to open a page and let the stories crawl in by themselves.

For Steinbeck (as for Zola), fiction was a laboratory experiment. He reserved his greatest love for the natural world — especially the mountains, valleys and surging shorelines of his beloved California. In one of his weirdest novels, To a God Unknown, his ranch-building protagonist, Joseph Wayne, makes love to the earth in one scene and, in another, speaks with his dead father’s spirit through an old tree. If any religion appealed to Steinbeck, it was simple raw pantheism.

Born in California’s Salinas Valley in 1902, Steinbeck was raised near — and often returned to — his ‘home ocean’ of the Pacific. Unlike his slightly older contemporary Hemingway, he possessed a ‘laid back’ California disposition. Rather than seeking out a ‘lost’ generation in Europe, he lazed around with friends, wrote books in shacks and trailers, went crabbing and cooked food over driftwood campfires.

He preferred fishing to bullfighting; and rather than take a rifle out to bag big game in Africa, he financed a scientific research expedition to the Sea of Cortez, where he and his friends catalogued creatures in scientific notebooks. For Steinbeck, the world was so abundant with pleasures that there shouldn’t need to be any Darwinian battle for survival (which is why the cruelties of the Associated Farmers made him so angry). For him, California was a vast plenitude filled with cheap wine and warm temperatures. In such a land, people could afford to be generous.

William Souder’s Mad at the World is the first significant biography of Steinbeck since Jackson L. Benson’s much longer 1984 volume, The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer. It is readable, admiring and compact, and provides a narratively energetic look at a man who suffered many of the same weaknesses as his characters — for booze, benzedrine, depression and bad marriages. But also like his characters, Steinbeck got up every day to test himself all over again, by writing a new book or embarking on a new adventure.

He spent many months visiting California’s migrant camps to research Grapes, worked as a war correspondent in both the second world war and Vietnam, campaigned for his liberal hero Adlai Stevenson and for publicly funded health care, wrote excellent movie scripts for Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! and Hitchcock’s Lifeboat and never stopped doing good work until he died of heart disease at the age of 66. Even late in life, his restless nature compelled him to hit the road with his French poodle in a well-decked out three-quarter-ton truck to ‘rediscover’ the ‘monster land’ of America, and he produced his last bestseller, Travels with Charley. Like Orwell (the British writer he most resembles), he never stopped sending himself on expeditions to better understand the world he wrote about.

Over several decades of consistent and furious literary production, Steinbeck explored the history, people and geography of his native California just as powerfully as Faulkner did the South; but he never received the same critical accolades — especially in his own country. He was often unfairly dubbed a one-hit wonder for The Grapes of Wrath; many of his best novels — the short, comic ones such as Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row — were unfairly dismissed as minor or non-‘serious’ — and his failure to exalt the humanity of his characters made him unpalatable to those who felt that novels should elevate the idea of being human, and not reduce it to animal exigencies.

Shortly before Steinbeck received his 1962 Nobel Prize, Arthur Mizener condemned his work in the New York Times for its ‘mystic sorrow’; but what Mizener didn’t understand was that ‘mystic sorrow’ was exactly the point. Steinbeck always expressed great empathy for those sad, aspiring and doomed creatures that were so much like himself; and it always made him angry to see them taken advantage of by, as a more appreciative critic noted, ‘an economic system that encourages exploitation, greed and brutality’. The best any person could do was to keep trying and failing, and wake up to do it all over again. ‘Mystic sorrow’ is all they (or we) could ever hope for.

Souder writes well, and this is a good place to start reading (or rereading) about Steinbeck. But Mad at the World sometimes feels a bit too terse and cursory, especially in the last 50 pages, and falls short of communicating a strong sense of the complicated, emotional life of a very complicated, emotional writer. For example, in his earlier, more extensive biography, Benson spent a full page describing the only meeting between Steinbeck and Hemingway (it was a disaster). At a Manhattan bar, John O’Hara showed Hemingway a blackthorn walking stick that had been passed down by Steinbeck’s father, and which Steinbeck had presented to O’Hara as a gift. In reply, Hemingway showed off his muscles by breaking the stick over his head and claiming the stick wasn’t an actual blackthorn. Steinbeck never spent time with Hemingway again. Who could blame him?

Souder’s version of the same story is reduced to this: ‘Hemingway had interrupted the otherwise dull evening by breaking a walking stick over his own head to prove he could.’ In such passages, something vulnerable and human about Steinbeck gets lost in translation.

Comments